Publisher: Middlebrow Books

Release Date: July 01, 2020

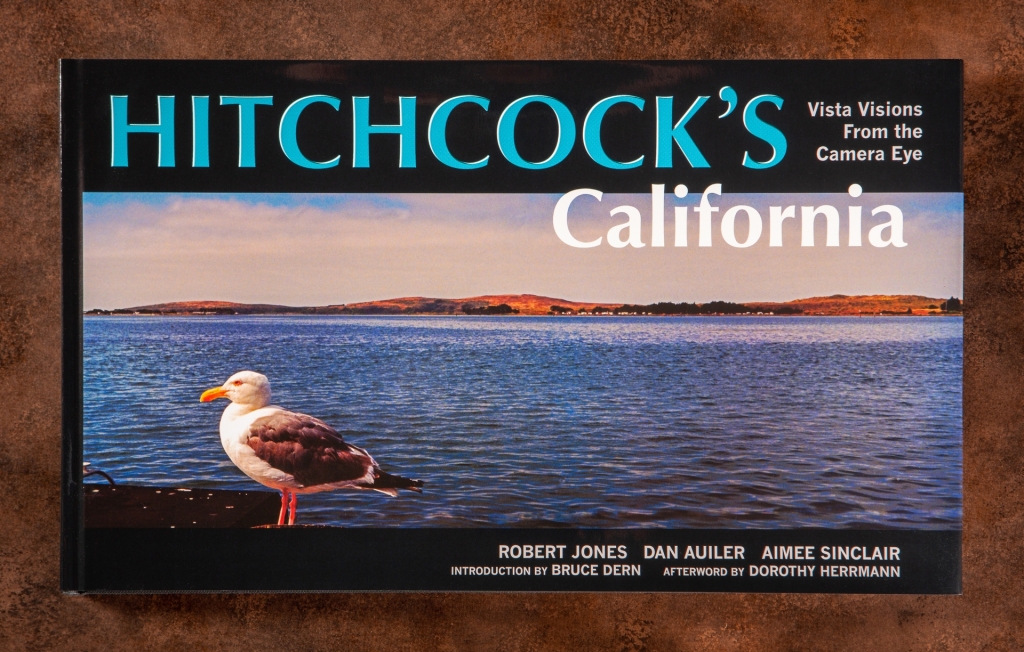

A Conversation with Robert Jones

“Hitchcock’s California: Vista Visions from the Camera Eye” celebrates (and re-creates) images that evoke scenes from many of the great director’s most famous films—including Notorious, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds, and a great many more classics. It was a labor of love for Robert Jones (the book’s primary creator) and a treat for Alfred Hitchcock’s fans. Jones’s excellent location photography is supplemented by photographs created by Aimee Sinclair that re-create memorable scenes from “Hitch’s” greatest movies and commentary by Dan Auiler (author of “Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic” and “Hitchcock’s Notebooks“).

Alfred Hitchcock Master is honored to have had the opportunity to talk to Robert Jones, Aimee Sinclair, and Dan Auiler about their incredible new book:

AHM: How were you introduced to Alfred Hitchcock’s work, and why do his films appeal to you?

Robert Jones: I was introduced to Hitchcock when I first saw Psycho. I was only nine, and it scared the daylights out of me!

His films appeal to me because he defined the suspense genre. I don’t mean this in an academic sense: His films are seldom “dated.” You chew your fingernails for the exact same reason while watching Robert Walker retrieve his cigarette lighter in 1951 as you do in 2019. Strangers on a Train is just as suspenseful then as it is now. Also, Hitchcock is the same director in nearly every one of his movies. Each film builds on the previous, and is building up to the next. He truly is an “auteur.” You may find it hard to believe that the director of Champagne is the same guy who directed Family Plot, but only because of the artifice of the silent movie, and the panoply of acting affectations that go with pre-talkie movies, as well as all the technical advances that occurred subsequently. Also, he hadn’t yet cemented his “Master of Suspense” reputation (although, you can imagine that the director of The Lodger would go on to direct so many great suspense thrillers). But you can instantly get that the director of The Lady Vanishes, North by Northwest, and Family Plot is one and the same—each are indelibly “Hitchcock.” That consistent quality carries through on most of his films. You aren’t left with the feeling that anyone else could have directed them.

AHM: Do you have a favorite Hitchcock film? Why is this your favorite?

Robert Jones: Vertigo, because I consider it the most perfect work of art ever created by Western civilization. I truly do. The photography, the settings, the colors, the wardrobe, Bernard Herrmann’s haunting score. It’s so beautiful, so heartbreakingly perfect, it’s not only a movie—it’s its own world. And, you get sucked into it, and don’t want to leave. One can see why James Stewart becomes obsessed with Kim Novak, because so do we. I can think of no more perfect expression of the Pygmalion myth than Vertigo. “But, she’s an illusion,” you might say. Well then, can you think of a single instance in which an “illusion” seems so real? This is why Vertigo works, on a very visceral level. It addresses every unattainable love we’ve ever fallen for—because it so vividly captures that fleeting moment in which she has been attained. Anyone who’s ever been engrossed by an all-consuming passion for another is a sucker for a movie like Vertigo, because, like Stewart, you don’t ever want to let go and have to leave.

AHM: Is there also a least favorite?

Robert Jones: My least favorite would be either Rich and Strange or Waltzes from Vienna. These pictures definitely have their moments, but by-and-large, they’re just kind of asterisks in Hitchcock’s output. Of his later films, it would have to be either Torn Curtain or Topaz—for the movies they could have been. Torn Curtain, if Bernard Herrmann’s incendiary music had never been so injudiciously dismissed, and Topaz, if Hitchcock had kept his nerve, and left the riveting duel scene in the release prints.

AHM: I actually had a similar question for Ms. Sinclair. You mentioned in the book that you were fairly new to Alfred Hitchcock’s work when you signed on to this project. I am wondering if discovering his work has altered your perception of cinema in any way.

Aimee Sinclair: Discovering Hitchcock’s work through this project definitely altered my perception of cinema in many ways. I can see Hitchcock mirrored in the way many movies are made these days, through the dynamics of film, and how they’re acted. Watching his movies was like watching an evolution in cinema in and of itself, from his black-and-white Rebecca film to a couple of my favorites, Vertigo and Family Plot. I can see Hitchcock’s style throughout those films, but the way he delivers it and how he pushes cinematography to its limits to evoke a multitude of feelings from his audience, set the standards for movie-goer’s expectations.

AHM: Let’s talk about “Hitchcock’s California.” What can fans expect to find within the pages of your book?

Robert Jones: They can expect to be drawn into the Hitchcockian universe. From the first page to the last, the reader will have the feeling of this book as a companion piece to Alfred Hitchcock’s motion pictures during the height of his artistic powers, particularly Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds, and Marnie.

The main section is a portfolio of eighty panoramic photographs of California locations Hitchcock used in his most of his American productions. They’re an homage to VistaVision, which was Paramount’s widescreen process Hitchcock used in many of his films in the 1950s. And, although we live in the digital age, every one of these photographs was shot on 35mm film.

Another feature of the book is “Souvenirs of a Killing,” a series of seventeen scene recreations from Hitchcock’s movies created by photographer Aimee Sinclair. These are also on film, but most of them were shot on medium format film. We used these photographs to set the tempo between the book’s essays, main portfolio, and interview. Many of them are MacGuffins, and really work as stand-alone photos—kind of like movie posters—that pull the book together.

AHM: Okay, that leads me to my next question for Ms. Sinclair. What challenges did the “Souvenirs of a Killing” photographs present you with, and how did you manage to come up with all of the necessary materials required to pull them off?

Aimee Sinclair: Where do I even start? “Souvenirs of a Killing” had a lot of challenges that both Robert and I, as well as my very generous models—my siblings—had to overcome. I think two of the big challenges were distance and setup. I live in Indiana, and Robert lives in Minnesota. This was a big challenge for me because I wanted to give Robert the results that we both desired for the book, but when you’re relying on phone calls, video chats, and screen shots to accomplish something, it can get tricky and frustrating. Robert, however, was always very patient and extremely precise about what he wanted out of a photo. Because of this, I was able to get clear directions of what needed to be done for the photos.

The second challenge was setup. Without a proper studio, there were a few times that my siblings and I had to get creative for shots. I remember doing the Dial “M” For Murder shot and my sister having to lay halfway off her bed backwards, with her arm at just the right angle to get the lighting on the scissors the way we wanted, so we would get that little bit of glare – yet, keep the background dark. That is definitely hard to do with one light, set back in through hallway, into a bedroom, to cut across the scissors laterally, without illuminating my background. As far as materials go, Robert was again the diligent party who knew exactly what he wanted and spared no expense ordering each piece specifically for each of the shots to replicate the movie screenshots perfectly. His children, Evan and Sarah, were also amazing help because they painted all the backdrops for Robert to photograph on film and insert digitally after both sets of film had been developed.

AHM: Another section of the book is called “Persistence of Visions.”

Robert Jones: The title is an allusion to the illusion that when we’re watching a motion picture that we’re seeing a continuous flow of motion, when we’re really seeing a series of images rapidly projected. This is the section of the book where I am interviewed by Dan Auiler (a noted Hitchcock author). We discuss how the project came to be, Hitchcock’s artistic vision, and how he worked memorable locations into his pictures. We had fun with it—it was a real conversation between two guys who are really enthusiastic about Hitchcock, but we didn’t want it to seem dry and detached. So, if we veered off topic (talking about Billy Wilder, Orson Welles, or John Huston, for example) it’s still on-topic, because this was the time period in which Hitchcock operated. He didn’t exist in a vacuum.

Dan Auiler: Robert had brought me in fairly early, in the fall of 2014, and I have to say I never wavered in my belief that this was a great project. Robert is a great photographer and an expert on Hitchcock in ways that I’m envious of. My favorite photographs are certainly the Vertigo material, for obvious reasons.

AHM: How did you arrive at the idea for this book, and what challenges did you face in order to make it a reality?

Robert Jones: The idea for the book sort of just came to me. I am always working on many different photo projects, documentaries as well as pictorial essays. Hitchcock’s California falls into the latter category. This particular idea came to me as I was photographing a boat cutting across Bodega Bay one dusky August evening in 2014. I thought to myself, “Has a photographer ever done a photo essay on the California locations Alfred Hitchcock used in his movies?” It had never been done before, not in a comprehensive way. Photographer Cindy Bernard had made recreations of scenes, but in a limited series. The authors of Footsteps in the Fog limited their very thorough book to the San Francisco Bay area, but the photography in it was strictly limited to documenting the myriad places related to the text; its intent was not artistic in nature.

I realized that I had better be able to deliver photographs that would be able to stand up to the original movies. Movies, by the way, that were some of the most beautiful and technically challenging ever photographed. So, immediately, I understood what a daunting undertaking I had ahead of me.

The challenges I had mostly had to do with the fact I live in Minnesota. If I lived in California, I could have wrapped up photography within a year, easily, going out on weekends to shoot. Instead, I made many trips over a four-year period, so each trip had to be mapped out to hit certain spots at the right time of day so I’d have the right lighting.

Other challenges came into play when Aimee and I were working on the “Souvenirs” photographs. Getting sweaters knitted, license plates stamped exactly to specification, finding the right hound’s tooth blazer, green ink blotter, and even Western Union telegram blanks—it was a lot of legwork getting this all done, and done on time, but we did.

Ironically, the one area which I thought would present the largest challenges didn’t. My first choices for writing the introduction and afterword to Hitchcock’s California were actor Bruce Dern and biographer Dorothy Herrmann—and both of them were very professional, and pleasant to work with. They both lent their own unique perspectives—Bruce on working with Alfred Hitchcock personally, and Dorothy growing up with her composer father Bernard Herrmann—which worked really well in keeping with the “Hitchcock Universe” premise, as Dan Auiler identified it.

AHM: It’s an interesting idea for a book—especially since Alfred Hitchcock isn’t known for his location work. If anything, his films are sometimes criticized for being too artificial due to his preference for studio work. Did Hitchcock use locations differently than other directors?

Robert Jones: I don’t necessarily think Hitchcock used locations any differently to how his contemporaries used them. Realize that he worked during the height of the studio system. By the time Hitchcock arrived, the major studios had already created this huge infrastructure of sound stages, permanent sets, and backlots, on which almost all the pictures were shot. Warner Bros. had a huge ranch for outdoor shooting, for example. The movie industry used the Alabama Hills, outside of Lone Pine, in Inyo County, as a naturally majestic backdrop for its Westerns and films of many other genres—Hitch used it in Saboteur, a 1942 movie that criss-crosses the United States.

It wasn’t until the breakdown of the studio system that you saw a newer generation of directors “open up” their movies in a radically different way, by shooting more, or primarily, on location. The best examples from that period are John Cassavetes and Dennis Hopper; Hopper really revolutionized on-location movie-making with Easy Rider.

Outside of Westerns, the only American film I can recall that really used a location in a subtle, but substantial way, was Orson Welles, when he turned Venice, California, into his set for Touch of Evil in 1957. Coincidentally, that was the same year Hitchcock used San Francisco and San Juan Bautista roughly the same way in Vertigo.

I would say that he doesn’t go overboard like some directors. In Vertigo he uses two California locations for major set pieces: The Golden Gate Bridge, and the bell tower (which doesn’t exist in reality) at the Mission San Juan Bautista. There is a sequence in which Jimmy Stewart tails Kim Novak’s Jaguar, driving down the vertiginous streets of San Francisco. Just a block up the hill on the very street where Stewart’s character’s house sits—Lombard Street—is the famous “crooked street,” a section that zigs and zags downhill amidst terraced gardens. Needless to say, Hitch didn’t use this section of road in Vertigo. To have done so would have broken the suspense and turned the scene into a needless set piece.

Would Hitchcock have used that stretch of road? Yes: If it was integral to the movie. Take Stewart out of that vehicle and replace him with an inebriated Cary Grant, and absolutely I can see Hitch using that crooked street—for Roger Thornhill to careen recklessly down. But, as we know, Vertigo is not North by Northwest!

AHM: You mentioned that all of the book’s photos were shot on 35mm film. Why was it so important to you to shoot these images on film, and how did it change the way you approached the photographs found in this book?

Robert Jones: It’s important to me, because to me, it’s not a film if you’re watching a digital projection of a digital motion picture. Film is the medium. If film is not used, in even one step of the moviemaking process, then how can it be even called a “film”? If every step is captured and projected digitally, then what you’re watching is a glorified video. It’s not “film.”

It didn’t change how I approached the photography in this book one iota. I’m a holdout, one of a dying breed of photographers who still works exclusively with actual film. In this case, 35mm film. I shot it on the Hasselblad Xpan panoramic camera, which is very much akin to Paramount’s VistaVision widescreen motion picture camera. Many of the actual rolls of film I used have been sitting in my freezer nearly twenty years: The first exposure I shot was on long-expired Kodak Vericolor III print film, in 2009 (the eucalyptus grove along U.S. 101 in San Benito County; the film expired in 1997). The exposures are grainy, but the grain gives the shots character. When I threw myself into this project five years later, I chose Agfa-Gevaert, Fujifilm, Ilford, and Kodak Professional films that I felt captured the mood or feel of certain movies.

AHM: Actually, the switch to digital is somewhat depressing. I’m glad that it exists, but I don’t like that it has become the go-to medium. The fact is that movies have lost a certain dream-like quality that is extremely beautiful (and sometimes haunting). VERTIGO would be a radically different film if it had been shot on digital cinema cameras (even if the compositions were exactly the same.) The same can be said of a great many films. What’s more, going to see movies in a theater is a different experience now. It just doesn’t feel the same. I also think that the photochemical process forces filmmakers to make certain decisions that many recent filmmakers simply aren’t making. In any case, it is difficult not to wonder what Hitchcock would think of the dominance of digital.

Robert Jones: I cannot surmise what exactly Alfred Hitchcock would think of it all. So, I won’t. What I will say is here is a director who used painted backdrops considerably as late as 1964 in Marnie. This, right after making the most technically advanced motion picture ever made, The Birds, just the year before. There are shots in The Birds you would never even think were special effects shots (for an in-depth study of how Robert Burks, Ub Iwerks, Albert Whitlock, and Ray Berwick combined their respective talents to create the visual world of The Birds, read Camille Paglia’s monograph she wrote on it for the British Film Institute). Hitchcock did not abandon the methods he learnt for staging and photographing motion pictures, merely because they were no longer in vogue. Dan Auiler makes the observation in our book that Hitchcock’s 1953 film I Confess is the most influenced by his early training in Weimar Germany. He used lighting schemes more at home with Fritz Lang’s or F.W. Murnau’s films from the 1920s, which cinematographers in the 1950s were using a flatter tonal range that was more documentary in its feel, relying less on backlighting than they did in the 1940s.

That said, even experiencing digital projections of film originals is a bit off-putting. That is because our minds perceive the “flicker” of cellulose acetate projections differently to how we sense the “rolling” images of a video or television projection, which is what digital theater is. When I saw Universal’s 4K digital “restoration” of Vertigo last year in San Francisco, for the 60th anniversary screening, it was gorgeous. But, it could not hold a candle to the 70mm print I saw projected of the actual restoration Robert Harris and James Katz did of Vertigo in 1996. The sheer beauty of that print was something akin to viewing the stained glass in the Notre Dame Cathedral. I still shoot on E-6 transparency film; it’s the closest thing there is to motion picture print film. Viewing slides on a light table is very much like viewing small vignettes of stained glass. Digital will never be able to recreate the imperfect perfection of that.

Take what is arguably the most famous portrait of the second half of the twentieth century, Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl. It is not so sublimely beautiful solely because of its subtle lighting, and lovely subject. It was also shot on Kodachrome slide film, and one can sense the translucence of the original slide, even when viewing a four-color halftone-screened print of it. In film, the medium is, to a great extent, the message.

AHM: Did this project change the way you think about the director’s work or about the way that he used locations in his films?

Robert Jones: Yes, on both accounts. There’s a line from Sunset Boulevard, in which William Holden plays a B-picture screenwriter: “Audiences don’t know somebody sits down and writes a picture. They think the actors make it up as they go along.” The same could be said for how a picture is filmed. We assume that a crew just sets up its cameras, microphones, and lighting and sound equipment on location, and films a scene. But, in watching the original movies—paying close attention to detail—I realized what intricate work it was piecing so many different types of shots together in order to make a scene appear seamless. The scene of Kim Novak jumping into San Francisco Bay in Vertigo is a perfect example of this. You have an establishing shot of Stewart’s car following hers. Then, though a series of rear-projection process shots, insert shots, special effect shots photographed in “the tank,” and location shots, Hitchcock, cinematographer Robert Burks, cameraman Leonard South, and process photographer Farciot Edouart created the illusion that the viewer is seeing an uninterrupted sequence filmed in a single location.

What that did was make me especially aware of how a movie studio’s crew works as a team, in order to realize the director’s vision. In his introduction, Bruce Dern mentions that Hitchcock’s genius was that he knew every single person’s name and job on the set. But, in order for Hitchcock’s genius to shine, it had to be fleshed out by these dozens of cast and crew members. That’s a very special kind of camaraderie, like an Army unit’s.

AHM: As a die-hard Hitchcock fanatic, your photos make me want to visit a lot of these locations. I’m really envious. What was it like to visit the same locations that were immortalized by Hitchcock on celluloid? Do you have a favorite location? Why was this your favorite?

Robert Jones: What was it like? It’s like, in most cases, a sort of calm comes over you. “I found it, I’m here.” Dan Auiler said “You can sense Hitchcock’s ghost.” So, I had that in the front of my mind. That sort of reverence pianists have when playing a Brahms or Rachmaninoff piano concerto. Meaning, you’d better have the chops to pull it off, otherwise you’ll look disingenuous. The phrase “a tough act to follow” passed through my brain’s transom more than once—I had to be like Arthur Rubinstein, and rise to the occasion.

My favorite location of all was the folded hills outside of Gorman, a lonely spot where Janet Leigh parks her automobile to get a catnap in Psycho. It just felt the truest, and the most purely untouched. It hadn’t “aged” been “updated” or become a tourist spot. It was just as Hitchcock’s crew had found it, so when I photographed it, I didn’t feel I had to change anything about the composition or framing. It was what the Ansel Adams f/64 crowd would call a “Zen moment.” Which is funny, because I didn’t get the same feeling at the Big Basin and Muir Woods redwoods parks, because they were so overrun by tourists.

AHM: It’s remarkable just how little some of these locations have changed over the years. For example, some of the locations from SABOTEUR don’t seem much different in your photos than they appeared in the film! Were these places instantly recognizable upon arrival? This may seem like a silly question, but sometimes you don’t recognize a location until it is pointed out to you.

Robert Jones: You’re quite right about the Alabama Hills, actually. I knew which rock formations this otherworldly place had that I wanted to photograph. Finding them was a little harder. Fortunately, a Lone Pine resident helped me to locate them, and they were instantly recognizable, mainly because I had seen them in so many other movies. The director who most memorably exploited these unique rocks was Ida Lupino, in her 1952 thriller, The Hitch-Hiker, for RKO.

AHM: The panoramic photos of certain SABOTEUR locations make me wish that he was shooting VistaVision in the 1940s. I think that the film could have benefited from the process. Of course, I understand that the process didn’t even exist at that time. It was formed after the advent of television to lure people back into the cinemas.

Robert Jones: Your observation is quite prescient. When I photographed locations from these earlier films (Rebecca, Suspicion, Foreign Correspondent, Saboteur, Shadow Of a Doubt, Spellbound, Notorious, Under Capricorn, and Dial “M” for Murder), I had to deal with the technical challenge of shooting them “widescreen,” but doing so in a way that didn’t take the reader outside of the experience of viewing those motion pictures.

Certainly, there is more information on the sides of the photographs, but I kept Billy Wilder’s sarcastic observation about CinemaScope in the front of my mind. Wilder said the widescreen process was the ideal format for a movie showing “two dachshunds kissing.” What he was getting at was that the aspect ratio lent itself to ridiculously elongated compositions, if the director of photography wasn’t paying too close attention. So, I tried to make the compositions not appear as though they’d been squeezed out of a pastry tube.

AHM: There’s so many terrific photographs in the book. Are you partial to any of them? Which are your favorites?

Robert Jones: Thanks, I really appreciate the compliment. There are so many of them, each for their own reasons. I would say the one singular photo is the cover shot. I was photographing Bodega Bay, futilely attempting to get a shot of seagulls flocking into the frame. They absolutely would not cooperate. This one gentlemanly gull, however, landed right in front of my tripod, and politely ate each breadcrumb I put before him, and then, when he was finished, stood in profile long enough so I could get a portrait of him with the bay and the hills as the perfect backdrop. He did this five or six more times—he was so patient! When I got the film back from the lab, I noticed how the seagull looked so much like Alfred Hitchcock himself: The rotund figure, his unflappable visage looking so serious, yet sardonic at the same time. I immediately knew this would be the cover shot.

Others were shots that you think you saw in Hitchcock’s movies—but didn’t. The back cover shot of “Madeleine Elster” wearing Edith Head’s gray suit, holding a nosegay of flowers against the background of the Golden Gate Bridge is a perfect recreation of the same shot in Vertigo. Except it’s not! Madeleine wasn’t wearing gray in that scene. Same with the shot of “Norman Bates” stalking the Bates Motel parking lot from Psycho, butcher knife in hand, at Universal Studios. Remember: “Mother” held the knife, not Norman.

Other shots are my favorites for the technical challenges involved: The photo of seagulls swooping in on Bodega Bay from The Birds was a photo montage, pieced together by Steve White in Photoshop; he took Aimee Sinclair’s gulls from Ormond Beach, Florida, and wove them into the picture so perfectly, you’d never suspect they weren’t Sonoma County residents. Another was the exposure I made of Father of the Forest at Big Basin Redwoods State Park. In the scene in Vertigo, shafts of light stream through the mist between breaks in the trees, it’s so sublimely beautiful. But, I didn’t have that kind of subtle fog going on by the time we arrived. My kids created some impromptu mist by running around in circles on the dirt trail. They kicked up so much dust, it looked as though it were mist! One second, they’re running around like Wyle E. Coyote; the next, they’re gazing in awe at the redwoods!

Artistically, my favorite is the panoramic exposure of San Francisco from my perch on Twin Peaks. It was of crucial importance to get this shot as close to the movie as possible: It marks the transition of Vertigo from Barbara Bel Geddes visiting Scotty at the mental hospital to a beautiful, bittersweet panning shot of the city where Jimmy Stewart will have to put the pieces of his life together. I needed to simultaneously capture the mist coming off the bay, the subtle tones of the hills outlying the bay, and the brilliant whites and rich colors of San Francisco’s buildings. It just had to match! I had run out of film and, on my drive back to San Francisco from Bodega Bay, I called Aimee Sinclair in a panic. I explained what I needed the film to do for this particular shot, and asked her to find me a camera shop in the city while I drove. She laughed and told me I didn’t need a camera shop, just a drugstore or supermarket. She explained why Fuji’s Superia 200 consumer film was perfect for just that sort of lighting situation. And, once I got the negatives back from the lab, she was absolutely right—thanks to Aimee, I nailed that shot!

AHM: Just out of curiosity, why did the Fuji’s Superia 200 work so well for that shot? I am interested in such technical revelations.

Robert Jones: Fuji’s Superia 200 consumer-branded film, is the end result of decades of research the Japanese photography company has made in constantly improving its film emulsions. Their consumer film of today, for instance, is technically superior to its own professional film from the 1990s. Superia has a very wide exposure latitude, which means how many different levels of lighting it can capture within a single exposure. Because Superia uses multiple layers in its emulsion, it can accurately render about five stops of lighting without any noticeable drop off of accuracy in the film’s tonal range. In other words, it “sees” a scene with different levels of light the way the human eye does. Now, Fuji’s professional film 400H, would have been marginally preferable to Superia, but the feel of the color would have been slightly off. For some reason, that Fuji drugstore film captured the feel of the colors exactly as the Technicolor IB print of Vertigo did 61 years ago.

AHM: One of the photographs of Point Lobos State Park reminds me of the opening of REBECCA (“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.”). What scene from the film was shot at this location?

Robert Jones: You’re spot on. It’s the movie’s first scene, with Joan Fontaine’s narration, right after the opening titles. Fortunately, the roads at Point Lobos lie beneath so much canopy of trees, they naturally obscure the light. I grabbed that shot with the camera on the tripod, so I could slow down the exposure, by placing a blue filter in front of the lens. With the swaying leaves, it created a dreamy, gauzy feel. It feels like a night shot, which is what I set out to do. Shooting day for night was often used in Hollywood productions of the day.

AHM: I was also wondering if the photograph taken at the Arboretum in Arcadia, CA was the location of Alicia Huberman’s “accidental” meeting with Alexander Sebastian on horseback in NOTORIOUS. Is this correct, or was some other scene shot here?

Robert Jones: Again, you are absolutely right! It’s a bit overgrown with foliage now, but it’s the same trail, and—as you correctly guess it, still recognizable.

AHM: You made a comment in the book that mirrors my own personal feelings during the conversation with Mr. Auiler. He said, “Many directors aren’t imitating Hitchcock so much as they’re a caricature of what they think is Hitchcockian.” I’ve heard countless filmmakers comparing their movies to Hitchcock’s or describing them as “Hitchcockian,” but this only betrays their complete misunderstanding of his work. They don’t seem to understand how he builds suspense, and I sometimes question if they have even seen his work. Where do you think these directors go wrong, and why is there so much misunderstanding as to what it means for a film to be Hitchcockian?

Robert Jones: I think most of the misunderstanding comes from the fact that for generations now, the studios’ marketing arms use “Hitchcock” and “Hitchcockian” with such disregard to facts. It’s basically a come-on, a sales pitch.

Let’s talk about directors, then. I think this is because so many of them treat filmmaking as an intellectual pursuit first-and-foremost. But, it becomes a self-defeating exercise in futility. The best way not to make a “Hitchcockian” picture is to try to make one. But, there is only one Hitchcock. The director’s mind, like Norman Bates’ mind, thus becomes bifurcated: The director has to be Hitchcock and not-Hitchcock simultaneously. No wonder their movies seem so schizophrenic!

Of the best movies Hitchcock never directed, that could be classified as “Hitchcockian,” only one of them (Blue Velvet, dir: David Lynch, 1985) can be regarded as “artsy.” But, David Lynch has his own idiosyncratic genius—never for a moment does the audience get the notion he makes movies in order to be compared to any other director. His films stand on their own two feet.

But, movies like Charade (Stanley Donen, 1964), The Hitcher (Robert Harmon, 1984), The Edge (Lee Tamahori, 1997), and Breakdown (Jonathan Mostow, 1997) were made by directors out to make movies. The artiness is almost non-existent, because the primary focus of these movies was the story itself, and putting it on the screen for maximum visual and emotional impact. These pictures’ art—like the best special effects sequences—consisted in concealing their overt artistic effects, and instead concentrating on the art of capturing and holding their audiences’ interest.

Today, the story gets buried beneath so many affectations by directors who seem trapped in film school. I saw a movie recently, in which every shot was a trick shot, a gimmick shot, an overhead shot, a slow-motion shot, or an extreme close-up. The soundtrack was equally cliched—was it really necessary to magnify the sound of the protagonist’s beating heart so often to communicate the pressure he was working under?

The movie’s story was excellent, as was the acting—but all that got buried under layer after layer of a murky cobalt-blue color scheme, CGI and typographical overkill, and the need of the director to impress. It was so ridiculous! The story was subordinated to the movie’s artifices. This was not even a suspense picture, or action picture. It was a historical picture—and it rightly flopped at the box office.

I think that directors need to look at what make Hitchcock so unique. It was that he subordinated the motion picture’s techniques to the service of telling amazing stories. Look at the director whose films Hitchcock consistently admired, who also happens to be my favorite director, Billy Wilder. The exposition of Wilder’s movies are more along mise-en-scene narration lines than Hitchcock’s, but it would be a mistake to characterize Hitchcock as a director who solely used montage. He didn’t. Double Indemnity, Sunset Blvd., and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes are quite similar, in how they unfold, to Hitchcock pictures. With some editorial and camera changes, they each could easily have been Hitchcock pictures.

That’s the key, I believe, to why the term “Hitchcockian” is so elusive for so many directors. They see him as a gimmicky director who used a glossy bag of tricks to get his movies across. He was anything but. By fixating on technique, they overlook his masterful storytelling abilities, the wonderful plotting, the finely crafted dialogue, the glances, gestures, and body language Hitchcock employs that say so much more than dialogue alone. This is the storytelling in which Alfred Hitchcock excelled. Take away the story, and all you’ve got left is a highlight reel.

[Note: Some of the opinions expressed in this interview are not necessarily shared by Alfred Hitchcock Master. Please be respectful to others in your comments if you wish to dispute any of these opinions. This is a friendly community.]

Interview by: Devon Powell

Reblogged this on cinemaliterate.

Fabulous interview! I learned a lot and want to buy the book. What a fun assignment–going to iconic spots for a shot.

Thanks! The pre-order should be up March 29th. We are also running a giveaway at our Facebook page. We’re giving away 53 copies of the book here: https://www.facebook.com/HitchcockMaster/

I thought that you might be interested.

great director