Distributor: Universal Studios

Release Date: May 10, 2022

Region: Region Free

Length: 02:00:04

Video —

4K UHD: 2160P (HEVC, H.265 – HDR10)

Blu-ray: 1080P (MPEG-4, AVC)

Main Audio: 2.0 English Mono DTS-HD Master Audio

Alternate Audio —

4K UHD:

2.0 Spanish Mono DTS Audio

2.0 French DTS Audio

2.0 German DTS Audio

2.0 Italian DTS Audio

2.0 Japanese DTS Audio

Blu-ray: French Mono DTS Audio

Subtitles —

4K UHD: English SDH, Spanish, French, Italian, German, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Norwegian, Japanese

Blu-ray: English SDH, Spanish

Ratio: 1.85:1

Notes: These are the same discs included in the “Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection: Volume Two” boxed set. The package also includes a digital copy of the film.

“I didn’t say, ‘I’d like to do a kidnapping film.’ What interested me about a story like Family Plot was that it was two sides of a triangle meeting at a certain point… That was the shape of the film, and the climax — the apex came when these two totally unrelated elements came together. And they came together just as the leading lady rings the front doorbell of the house which contains a kidnapped bishop. And that’s what appealed to me was the structure of this story, and the kidnapping and all those elements were part of it but certainly no great inspiration to me.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Family Plot Press Conference, March 23rd, 1976)

It is interesting that Alfred Hitchcock would follow the dark and cynical Frenzy with the light and whimsical Family Plot. While it is true that there is a fair amount of cynicism in Family Plot, it is filtered through a rather optimistic lens. This is especially true when one compares it with Alfred Hitchcock’s source of inspiration for the film. The script was adapted from Victor Canning’s “The Rainbird Pattern,” but the differences between the novel and Alfred Hitchcock’s film go far beyond any changes that were made to the plot (and there were many). The tone of the novel was dark and pessimistic about much more than the characters and situations described in Canning’s story. Practically every character is met with a bitter end. It was much more in keeping with the tone of Frenzy. One can only speculate as to the director’s reasoning behind turning the film into a light entertainment, but I believe that it indicates a level of hope possessed by the 76-year-old Hitchcock… or perhaps I merely hope that this is what it represents.

Considering that his intention was to create a much lighter entertainment, it seems somewhat unusual that he should ask his former Frenzy collaborator to help him turn his ideas for his new project into a screenplay.

“After deciding on “The Rainbird Pattern,” the director offered the script assignment to Anthony Shaffer, who read the book but balked at ‘the sort of version that Hitch was describing — a sort of light, Noel Coward — Madame Arcati thing with Margaret Rutherford.’ … Shaffer agreed to think about it, but he had flashed the wrong signals, and Hitchcock phoned him a week later to say that his agent had made excessive demands. Shaffer felt Hitchcock was dissembling in order to avoid later confrontation over his approach.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Hitchcock rebounded from Shaffer with ease and decided to contact a more appropriate collaborator: Ernest Lehman. It isn’t difficult to follow his train of thought. After all, Lehman had worked on North by Northwest with the director.

“I felt very comfortable being back with him. However, before long I realized that our relationship was quite different. Many years had passed. We had both had successes and failures. We were different people now.” —Ernest Lehman (as quoted by Patrick McGilligan in “Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light,” 2003)

Despite the changes in both men, Alfred Hitchcock’s working method was very much the same as it had been while the two men were writing North by Northwest.

“The first forty-five minutes… are always warm up time, during which neither of you would dare commit the gross unpardonable sin of mentioning the work at hand. There are more attractive matters to be discussed first… How much more pleasurable [was this conversation], than to have to sit there, sometimes in terribly long silences, trying to devise ‘Hitchcockian’ methods of extricating fictional characters from the corners into which you painted them the day before.’ —Ernest Lehman (as quoted by Patrick McGilligan in “Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light,” 2003)

It was usually Lehman that launched the conversation into writing-mode, and the men would trade ideas for whatever script problems that they were facing on that particular day (with Hitchcock having final say). When Lehman made suggestions of his own, it created a different kind of suspense for the writer.

“…You begin to talk, and he watches you, and he listens, and you watch him carefully, and you continue, and finally you’ve said it all. And then [Hitchcock] does one of several things. His face lights up with enthusiasm. Good sign. Or his face remains unchanged. Question mark. Or he says absolutely nothing about what you have just told him and talks about another aspect of the picture. Pocket veto. Or he looks at you with great sympathy, and says, ‘But Ernie, that’s the way they do it in the movies.’” —Ernest Lehman (as quoted by Patrick McGilligan in “Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light,” 2003)

Both men had rather robust egos. Lehman really didn’t like being subordinate to Alfred Hitchcock and preferred to write things the way that he wanted to write them. However, when one writes with Hitchcock it is understood that they are there to write what he tells them to write.

“‘I found myself refusing to accept Hitch’s ideas (if I thought they were wrong),’ Lehman recalled later, ‘merely because those ideas were coming from a legendary figure.’ The writer had grown weary of Hitchcock overanalyzing everything, and he simply wanted the go-ahead to finish. The silences between them grew longer, the disagreements awkward…

…Privately Hitchcock had decided that Lehman was ‘a very nervous and edgy sort of man’ who was deliberately giving him ‘a rather difficult time,’ as he complained in a letter to Michael Balcon in England. When he suffered a heart attack in September, Hitchcock went do far as to blame the episode (only half kiddingly, it seems) on the constant ‘nervous state’ induced by his arguments with Lehman.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Whether not the tense relationship between these two men actually had an impact on the final script is up for debate, but there it seems to have left its mark on the film’s infamous ending.

“…Again, Lehman toyed from time to time with the idea of resigning, and was persuaded back, grumbling but still fascinated. He ended incredulous at all the agony which had gone into the creation of such a slight picture, and amazed that so little of it showed. Finally, his main difference of opinion with Hitchcock was over the ending, which Hitch eventually wrote himself and submitted to Lehman, listened to his objections (mainly that the medium is shown throughout to be a fake, so to suggest that maybe she has a touch of psychic power is disturbingly inconsistent), discussed his alternate solutions, and then went right ahead and used his own version.” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Although, Hitchcock used the ending that he had written without Lehman, the writer’s issues were addressed in post-production.

“… [This] led to some redubbing in the New Year when the Hitchcock’s returned from their annual pilgrimage to St. Moritz. On a shot of Adamson’s back as he carries the drugged Blanche to captivity after she has tumbled to his true identity was dubbed a line referring to the diamond in the chandelier (not in the shooting script), which could just possibly explain away Blanche’s final revelation – maybe she was not completely unconscious at the time or heard the remark unawares. When Ernest Lehman saw the film, he was unhappy with the line, and suggested something less contrived sounding, while admitting that any line at this point was necessary contrivance. The line was re-dubbed using one of Lehman’s suggestions…” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Of course, writing Alfred Hitchcock’s “53rd feature” was the easy part (regardless of what the director might say in publicity interviews). The seventies were a challenging decade for the director, and both he and Alma suffered quite a few health-related scares. He was in the midst of several of these scares while preparing Family Plot (which was entitled Deceit during the film’s production).

“…Hitch had a succession of health problems that put him in and out of the hospital for most of the autumn –first, he had a heart pacer fitted, which he delights to show with some gruesome details of the surgical process involved. Then, as a result of a bad reaction to the antibiotics he was given, he got colitis, and once over that he had a kidney stone removed…

…By December 1974, when I saw him again, the production was moving toward its final stages of preparedness. The script was pretty well fixed, for the moment (the final production script bears evidence of some intensive final polishing around the end of March and the beginning of April 1975, but nearly all in matters of detail) …” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Hitchcock’s health would have a large impact on how the film would be shot. The director had originally planned quite a bit of location shooting, but it became obvious to everyone that the production would have to be tied to the studio. Of course, there were a few noteworthy exceptions.

“…The image of Grace Cathedral remained for the Bishop’s kidnapping, and with it some other unobtrusively San Francisco locations for the houses of various characters. At one time Hitch even considered doing the cathedral sequence in the studio, on the principal that all he really needed was one column and the rest could be matted in. But he discovered that in the studio the sequence would cost $200,000, so he decided he might as well go on location, and while he was there himself shoot the other San Francisco exteriors, which had formerly been assigned to the second unit.” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Special preparations were taken by the studio to ensure that Hitchcock could get around with relative ease. Thom Mount elaborated on some of the special measures that were taken to writer, Charlotte Chandler.

“…Mr. Hitchcock had a very hard time standing up for any lengthy period of time. Walking was not his strong suit by that time, so we took an old Cadillac convertible and a welding torch, and we cut the sides, and the back off of it, fitted a flat platform on the back of the Cadillac, and on that flat platform we put a chair for a cinematographer, as if it were a crane that was mounted on a hydraulic lift. Mr. Hitchcock would sit in the chair and move himself around in any direction and see in all directions. The Cadillac was moved all around the soundstage, even though they were interiors, just backing it into place, wherever it needed to be. And so, Mr. Hitchcock could move around” —Thom Mount (as quoted by Charlotte Chandler in “It’s Only a Movie,” 2006)

There were other issues to consider as well. Hitchcock took special care to go over his visual plans with his storyboard artist, Tom Wright. This was particularly true of the car “chase sequence,” because Hitchcock’s health issues would make it impossible to be present during some of the shooting of this particular sequence. It was necessary for the storyboards to be an exact replica of his vision, because the second unit would need them to follow Hitchcock’s design down to the last detail.

Even with these health issues as a handicap, the old master seemed sharp as a tack mentally. He even seemed maintain his equanimity while shooting the location footage at Grace Cathedral.

“The extras, as is the way with extras, want to act, to make the most of their few seconds [of] screen time with elaborate reactions, and dare to attempt discussion of motivation with the director… At one point, when the abduction of the Bishop is actually taking place, some extras at the back ask him to describe what is happening so that they will know how to react. ‘Can you see what’s happening?’ No. ‘Then there you are. You can’t see what’s happening, you just have a vague idea that something is. You don’t have to react beyond a slight show of curiosity.’” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Crowd scenes are always difficult, and to be able to direct a large number of people in a relatively short period of time takes more than just a small amount of mental stamina. This was always one of Alfred Hitchcock’s most accessible tools. Unfortunately, the production was not without a reasonable amount of stress, and there are certain problems that take more than mental prowess. Sometimes difficult decisions have to be made.

“Shortly after the successful location shooting in San Francisco some unexpected troubles arose with the shooting, acknowledged in a brief press announcement dated 13 June which stated that the character portrayed by Roy Thinnes had ‘undergone a conceptual change calling for a new character concept’ to be played by William Devane… Stories vary as to what lay behind this change, which necessitated reshooting and put the film, up to then a few days ahead of schedule, rather behind. (It was originally scheduled to take fifty-eight days to shoot, and the budget envisaged was a modest three and a half million, of which Hitch wryly remarked, about $550,000 would go on fringe benefits of various kinds that never show on the screen.)” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

One of the stories as to the reason that Thinnes had been re-cast with Devane was published on June 18, 1975, in Variety (a source that isn’t always particularly accurate). According to Variety, “Alfred Hitchcock and Roy Thinnes disagreed on the interpretation of the young actor’s role in “Deceit“ after a scene in San Francisco… Actor’s don’t tell Hitch; he tells them.” However, the Athens News Courier would quote Hitchcock giving a less dramatic reason for the actor’s replacement in an article published on June 1, 1976: “That came from miscasting on my part. He didn’t have a sinister quality.”

“…Given Hitch’s absolute and abiding horror of scenes and confrontations, it seems very unlikely that [a confrontation with Thinnes about the character] occurred, but rather that Hitch put into practice his often-stated principle that if he found he was not getting what he wanted from an actor his natural way of dealing with the situation would be to pay the actor off and start again with someone else. A spectator did describe to me the nearest thing to a confrontation when Roy Thinnes cornered Hitch at his regular table at Chasens’ during one of his regular Thursday dinners to ask him in some distress, ‘why?’ Hitch, equally distressed, just kept saying, ‘but you were too nice for the role, too nice.’”—John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Luckily, Hitchcock was particularly fond of both Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern. He allowed both actors a certain amount of freedom to interpret their characters, and his relationship with both of these actors was one of genuine affection based on mutual admiration and respect.

“I’ve made thirty films, and he’s the best director I’ve ever worked for. He’s also the most entertaining man, the best actor. He’s got style and personality, and he’s full of stories. Of course, people say he allows no freedom to actors. But there’s all the freedom in the world once you understand the ground rules. He explains what the shot is supposed to say and what you’re supposed to do. Then you give it! If you couldn’t do it, you wouldn’t be working for him in the first place. Nothing is left to chance except the actor’s improvisation. He’s concerned that the actor keep it fresh, alive, [and] new. He wants each shot to entertain him — then he knows the audience will be entertained.” —Bruce Dern (as quoted by Donald Spoto in “The Art of Alfred Hitchcock,” 1976)

When the picture wrapped on the 18th of August, the production was only thirteen days over schedule. Luckily, the title was changed from Deceit to Family Plot at some point during the film’s creation. The latter title was suggested by someone in Universal’s publicity department after Hitchcock had expressed his dissatisfaction with the original title. After making a market inquiry into the effectiveness of Deceit as a possible title, Hitchcock’s instinct was proven accurate. It didn’t seem to be an effective title for this particular film.

“I felt the word ‘Deceit’ suggested a bedroom farce. It suggested – It was rather a mild word. It didn’t carry any meaning with it. Pictorially, when one began to think about the word, ‘Deceit,’ there you had the woman in bed, the husband entering the bedroom, and the lover secreted behind the curtain… and that to me epitomized the word ‘Deceit.’ It wasn’t good, I didn’t think.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Family Plot Press Conference, March 23rd, 1976)

Alfred Hitchcock never really recovered from his falling out with Bernard Herrmann, and it was rather late in the postproduction process when John Williams was finally asked to provide a score for the film.

“Mr. Hitchcock had his office here at Universal Studios. And so, he apparently needed a composer for this Family Plot, and the executive those years in charge of music was a gentleman called Harry Garfield. So, it was Harry Garfield who recommended me as a newcomer, just having done Jaws, a very successful film, to Mr. Hitchcock. And I went to see him at his office, and we had lunch and had a chat and I left not knowing if he would engage me to do this or not. Then I got a call from Mr. Garfield the next day. It said, Hitchcock, yes, he would like you to do the score.” —John Williams (Plotting Family Plot)

The composer found the experience of working with Alfred Hitchcock instructive and is valuable as evidence against the insane claim that Alfred Hitchcock didn’t have an ear for music. He was in fact very aware of how different kinds of music altered a scene’s tone. He was also very aware of the effect that the absence of music could have upon the audience.

“I could tell you one little anecdote, also, about a scene in the film where we didn’t have a disagreement about where the music should play but a discussion. There was a room where the criminal had been, and the camera pans to the window, which is open. And the curtains blow in the breeze, and this reveal of the camera tells us the criminal has escaped.

But the orchestra was playing to drive the energy to people to go to discover where the criminal is. Driving, driving, driving… through the point where the camera goes through the door. And I continued the music when the camera panned to the window, playing it more. And he said, “You know, if you stop the music when the camera pans to the window, “the silence will tell us that it’s empty — he’s gone — more emphatically, more powerfully than any musical phrase.” And, of course, just the absence of music at that point… It was a wonderful lesson, really, in where to arrange the parts of the music in any film, which we call “spotting,” incidentally. That is to say, the spots are where the music is.” —John Williams (Plotting Family Plot)

When the film debuted on March 18, 1976, for a University of Sothern California preview audience, Hitchcock was quite happy with the student audience’s enthusiastic reaction. The director’s optimism cemented when Family Plot officially premièred opened at the benefit opening of ‘Filmex’ (Los Angeles International Film Festival) on March 21, 1976. The reaction here was also quite enthusiastic, and it looked like the director might have a hit on his hands.

Of course, an early review that was published in Variety on the December 31, 1975, had probably already spearheaded his optimum several months before the film was even released.

“Family Plot is a dazzling achievement for Alfred Hitchcock masterfully controlling shifts from comedy to drama throughout a highly complex plot. Witty screenplay, transplanting Victor Canning’s British novel, ‘The Rainbird Pattern,’ to a California setting, is a model of construction, and the cast is uniformly superb.

Bruce Dern and Barbara Harris are the couple who receive primary attention, a cabbie and a phony psychic trying to find the long-lost heir to the Rainbird fortune.

Dern is a more than slightly absurd figure, oddly appealing; Harris is sensational.

William Devane takes a high place in the roster of Hitchcockian rogues, while Karen Black, gives a deep resonance to her relationship with the mercurial Devane.” —Staff (Variety, December 31, 1975)

Vincent Canby also wrote an affectionate review for the New York Times, following the film’s release to the public.

“Not since To Catch a Thief and The Trouble with Harry has Alfred Hitchcock been in such benign good humor as he is in Family Plot, the old master’s 56th feature since he began directing films in 1922.

Family Plot, which opened at theaters all over town yesterday, is a witty, relaxed lark. It’s a movie to raise your spirits even as it dabbles in phony ones, especially those called forth by Blanche (Barbara Harris), a sweet, pretty, totally fraudulent Los Angeles medium, who nearly wrecks her vocal cords when possessed by a control whose voice sounds like Sidney Greenstreet’s.

But Family Plot isn’t about anything as esoteric as spiritualism and its sometimes-wayward votaries. It’s about good, old-fashioned greed, or, how to work very, very hard in order to make your fortune illegally. It’s one of the many invigorating ironies of Family Plot that its con people are so obsessed by their criminal pursuits they never realize the easier way would probably be the lawful one. Then, of course, there would be no plot, and a high regard for plot is one of the distinguishing joys of both Hitchcock and this new film…

…Blanche and Lumley, merged, make a single birdbrain, but one whom heaven protects and fortune smiles on. As performed by Miss Harris and Mr. Dern, they are two of the most appealing would-be rascals that Hitchcock had even given us. For that matter so are Adamson and Fran (she has no last name, which leaves her matrimonial state in Old World, gentlemanly doubt). Though Adamson is portrayed as being perfectly willing to murder, when cornered, he never succeeds, and Fran is the kind of kidnapper who prepares gourmet meals for her involuntary guests. The four are extremely good company, like Hitchcock himself when, in an expansive, genial, storytelling mood, even his digressions have digressions, but always to the point of some higher entertainment truth.

Hitchcock aficionados may well miss signs of the director’s often overanalyzed pessimism. Family Plot is certainly Hitchcock’s most cheerful film in a long time, but it’s hardly innocent. One of the things that figure prominently in the plot, though it happens long before the film starts, is the story of a young man who, finding his stepparents boring, pours gasoline all over the house and incinerates the offending pair. It’s a small thing, perhaps, but it continues the master’s franchise on the macabre.” —Vincent Canby (New York Times, April 10, 1976)

Roger Ebert was also positive in his statements about the film, giving it three out of four stars.

“Alfred Hitchcock has always preferred visuals to dialog, yet Family Plot opens on a talkative note. A medium, the slightly spaced-out Madame Blanche, is holding a séance with an eccentric old lady. They’re in the old lady’s parlor, surrounded by antiques and heirlooms and an abundance of deep shadows, and the old lady is involved in this incredibly complicated tale about events of years ago.

It appears that her late sister had an illegitimate child and, times being what they were, the child was given up for adoption. Then the sister died, and the child was lost track of, and now the old lady is afraid of dying and wants to make amends by willing her vast fortune to the child. Madame Blanche’s assignment: Find the missing nephew. He’d be almost 40 now.

If this were to be a routine story, the medium no doubt would recruit someone to play the missing nephew, and they’d share the vast fortune. But, no, this is a Hitchcock, so that would be far too simple. Madame Blanche does the unexpected thing: She sets out to find the nephew. And, as wonderfully played by Barbara Harris, she has such a sweet and simple faith in the possibility of everything that we almost think she’s right. She enlists the aid of her rather slow-witted boyfriend (Bruce Dern), a cabdriver and sometime actor. He’ll do the detective work, she’ll keep the old lady happy, and they’ll share a $10,000 reward.

Now comes a nice touch. As Blanche and her boyfriend drive home in a cab, they almost run down a woman. They miss and drive on, but the camera follows the woman. She is, inevitably, the wife of none other than the missing nephew. And the two of them are involved in a series of kidnappings with precious jewels as the ransom.

The way Hitchcock cuts, just like that, from one pair to the other — cheerfully flaunting the coincidence – reminds me a little of Luis Bunuel’s recent The Phantom of Liberty. It’s as if both directors, now in their 70s and in total command of their styles, have decided to dispense with explanations from time to time: Why waste time making things tiresomely plausible when you can simply present them as accomplished?

Family Plot opens, as I’ve suggested, with a rather large amount of talking, but it’s necessary to lay out the elements of the story. Hitchcock has a deviously complicated tale to tell, and he’s going to tell it with labyrinthine detail, and he’s not going to cheat — so he wants to be sure we’re following him. It wouldn’t be playing fair with his meticulously constructed plot to describe very much of what happens, but there’s a real delight in watching him draw his two sets of characters closer and closer, until they meet in a conclusion that’s typical Hitchcock: simultaneously unexpected and inevitable.

But I can, I suppose, admire a scene or two. There’s a moment in a graveyard, for example, when a gravedigger appears almost from out of Hamlet to regard a suspicious tombstone with the investigating cabdriver. Another moment in the same cemetery, as the cabdriver and a newly made widow stalk each other on grass paths, with Hitchcock shooting from above to make them seem captives of a maze. And a scene in a cathedral that’s Hitchcock at his best: A bishop is kidnapped, and no one moves to interfere because… well, this is a church, after all.

As his kidnappers and jewel thieves, Hitchcock casts Karen Black and William Devane. She does a good job in a role that doesn’t give her much to do, but Devane, whom I hadn’t seen before, is inspired as the criminal mastermind and missing nephew. He has a kind of quiet, pleasant, sinister charm; he’s oily and smooth and ready to pounce. And his aura of evil contrasts nicely with Miss Harris and Dern, who have no idea what sorts of trouble they’re in.

Family Plot is, incredibly, Hitchcock’s 53rd film in a career that reaches back almost 50 years. And it’s a delight for two contradictory reasons: because it’s pure Hitchcock, with its meticulous construction and attention to detail, and because it’s something new for Hitchcock — a macabre comedy, essentially. He doesn’t go for shock here, or for violent effects, but for the gradual tightening of a narrative noose.

Everything’s laid out for us and made clear, we understand the situation we can see where events are leading… and then, in the last 30 minutes, he springs one concealed trap after another, allowing his story to fold in upon itself, to twist and turn, and scare and amuse us with its clockwork irony.” —Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun Times, April 12, 1976)

A review published in the Independent Film Journal was also enthusiastic.

“For his 53rd film, Alfred Hitchcock has toned down the shock value and accentuated the humor in a deliciously complex comedy-suspense drama that will have audiences happily perched in the palm of its hand nearly every step of the way. Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern sparkle as two innocent tricksters whose search for a missing heir suddenly parallels the path of a pair of professional kidnappers. Great fun and bound to be a great hit.

Don’t be too surprised if this year’s Easter Bunny is portlier than usual, complete with multiple chins, a proudly out-jutting belly and only a few wisps of grey hair remaining on his scalp. Chances are he’s shown up in the trademarked form of Alfred Hitchcock, beckoning audiences to Family Plot, a beautifully constructed, literately witty and thoroughly involving comedy suspense-drama crafted with the sure hands of an impudent genius. Moving even further away from the shuddery sensibilities of his best-known films, Hitchcock seems to have approached his 53rd feature in a mellow and benign mood, spinning his complex web of suspense with a far greater accent on rich humor than on shock value, as if he didn’t want his audiences to feel even vaguely threatened or uncomfortable en route to their final catharsis. Stated simply, Family Plot promises those audiences one hell of a good time and should prove a rousing success at the box-office. The discomforting sense of menace may be missing, but in most respects Family Plot is still quintessential Hitchcock, a complex plot that begins as a tantalizing mystery, allows itself to be solved for the viewer relatively early on, and then shifts to pure suspense as its convoluted threads inexorably weave themselves together.

Beautifully scripted by Ernest Lehman from Victor Canning’s novel, The Rainbird Pattern, the film again taps that steady thematic vein that continually resurfaces in Hitchcock’s work: what happens when relatively innocent bystanders find themselves unwittingly — and dangerously — enmeshed in someone else’s criminal goings-on. In this case, the action cuts back and forth between two sets of protagonists, one of them greedy but basically innocent, the other coldly criminal, with both combinations destined to clash trajectories. The heroes of the piece, superbly played by Bruce Dern and Barbara Harris, are a beguiling pair of lower-echelon con artists contriving to track down the missing heir to a dowager’s fortune and hoping to earn a $10,000 finder’s fee for their trouble…

…More often than not, the intricate plot turns, and quirks of character are far wittier and deliciously entertaining than they are tension-provoking, a fact that may momentarily disappoint serious Hitchophiles expecting artfully visualized set pieces like the shower stabbing in Psycho or the potato truck scene in Frenzy. But the story is definitely the thing, and even if a key scene in which Dern and Harris are pursued down the highway by a murderous car doesn’t sustain itself long enough to muster any great emotional payoff, there are more than enough ingenious twists and a firm enough overlay of suspense to keep viewers raptly entertained from beginning to end.

Brightening things considerably and providing two of the most engaging characters ever to fill Hitchcock’s viewfinder, are Dern and Harris as a pair of good-hearted bumblers whose liveliness and emotional range firmly counters the kind of cool, cipher-like performances the director is noted for wanting from his actors. As their destined nemesis Devane checks in effectively as another suave but despicable Hitchcock villain, while Black, as his suddenly rebellious partner, conforms more closely to the cipher quality mentioned above. Strong support comes from Ed Lauter as Devane’s psychotically traditional henchman.

Technical credits, barring some of those curiously sloppy process shots Hitchcock seems to relish so much, are excellent, highlighted by a deliciously taunting score by John Williams. Piece by piece and in overall effect, Family Plot is as solid an entertainment as any audience — at any level — could ever hope for.” —S.K. (The Independent Film Journal, April 14, 1976)

Even Penelope Gilliatt’s review for The New Yorker was generous in its kindness towards Family Plot.

“With a kick on a cemetery headstone that has no body below (‘Fake! Fake!’ shouts the kicker), and a gentle, lethal plopping of brake fluid, the soundtrack of Alfred Hitchcock’s Family Plot firmly plants us in a world in which the hallowed is a hoax and the mechanically sophisticated is dangerous to treat as a plaything. Hitchcock has never made a strategically wittier film, or a fonder; and this in his seventy-seventh year.

The beginning reminds us that the Master has always wanted to direct, of all things, J. M. Barrie’s ‘Mary Rose;’ and, though he once cheerfully informed me that he has it in his studio agreement that he is not allowed to film the play, the wily old jackdaw has managed to smuggle a whit of Barrie’s fantasy into his new comedy-mystery. Mary Rose hears voices calling her from another world; at the beginning of Family Plot, when Barbara Harris, as a ravishingly pretty and constantly famished con-woman spiritualist named Blanche, is conducting a séance with a loaded old biddy named Miss Rainbird (Cathleen Nesbitt), Blanche speaks in the voices of a woman and a man from the Great Beyond. The voices confirm Miss Rainbird’s guilt about having long ago covered up the illegitimate birth of an heir to the Rainbird fortune. Then Blanche, exhausted by her bogus insights, returns from the Other Side and gratefully accepts a drink. ‘A double shot of anything.’

Blanche works hard to make her wide-eyed living out of the dead. The offer of a reward of ten thousand dollars if she can find the missing heir is an amazing windfall. She generally manages frugally. Her boyfriend (Bruce Dern) drives a taxi. They exist on hamburger-munching and sex, both of which are perpetually being interrupted by twists in the Rainbird-heir mystery and by shiftwork for the taxi company. The Bruce Dern character, called Lumley, puts up with deprivation better than his girl, whose temperament endearingly refutes generalities about women being too finely bred to have appetites. Blanche is a girl of simple longings whom fate keeps calorically and erotically ravenous.

Hitchcock has always thrived on making stories about couples. In Family Plot — written by Ernest Lehman, from an English novel by Victor Canning which has been transplanted to California — we see how his attitude toward casting has changed. Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern occupy the places that would once have been held by Grace Kelly and Cary Grant, or Kim Novak and James Stewart. The part of the glossy blonde (Karen Black) is now villainous, and the glossy blondness is a matter of a wig. Called Fran, she is in murderous collusion with a smooth diamond thief named Adamson (William Devane). Another couple. The two pairs are piercingly different. Blanche and Lumley adore each other, though they often seem about to throw lamps at each other; Fran and Adamson are partners in crime who cherish little love for each other and talk to each other with a formality that is eerily violent. There being no chivalry among thieves, Adamson unblinkingly sends Fran on dangerous missions by herself, for which she wears six-inch heels, black clothes, and the blond wig: at one’s first glimpse of her in this disguise she looks as if she might well be a man in drag. The music-hall sight is funnily linked to the way Blanche’s voice suddenly hits an air pocket and comes out as a baritone at the opening séance…

…[Hitchcock] often has a wryly amused view of women’s scares. I remember that he was once showing me his kitchen in Bel Air. Everything was spick-and-span. Not a cornflake visible. A desert for cockroaches. He opened a door, and icy air steamed out. The freezer locker: a whole room. I saw hams and sides of beef hanging from hooks like rich women’s fur coats in summer storage. Hitchcock courteously bowed me in first. I hesitated and looked back, imagining the door clanging shut behind me. He knew what I was thinking, and I knew that he knew. A Hitchcock scene was in our imaginations, and an equally Hitchcock flash of irrational fear had come to pass.

Each of his films has been full of moments of red-herring disquiet, but he has never laid such a bland set of ambushes as in Family Plot. The Master makes unsettling use of an oaken-looking woman in a jewelery shop, whom Blanche cheerfully asks if her sign is Leo; of a brick wall that comes open and then closes hermetically, causing steep claustrophobia; of a remote-control garage-door gadget; of a fragment of bishop’s red robe shut in the bottom of a car door in a garage, making one think of the gaudy socks of the unlosable corpse in The Trouble with Harry (1955); of an overhead shot of a weeping woman hurrying through a maze of paths in a cemetery, pursued by Bruce Dern; of a woman physician, a disgruntled old man in shirtsleeves, and identical-twin mechanics, who are successive false trails in Blanche’s chase; of a genteel chiming doorbell on the front door of the thieves’ house. Hitchcock’s ominous mechanical devices and his dark clues leading nowhere build up in us a farcical discomfiture. We are like oversensitive princesses troubled by peas under mattresses.

But Family Plot does not rest on the fostering of anxiety. Hitchcock allows himself a camaraderie with the audience which makes this film one of the saltiest and most endearing he has ever directed. It is typical of the picture that he should have the sagacity and technique to bring the terrifying car incident to such an un-troubling close. Only a very practiced poet of suspense could slacken the fear without seeming to cheat and end the sequence without using calamity. With this picture, he shows us that he understands the secret of the arrow that leaves no wound and of the joke that leaves no scar. Sometimes in his career, Hitchcock has seemed to manipulate the audience; in this, his fifty-third film, he is our accomplice, turning his sense of play to our benefit. There is something particularly true pitched in his use of the talent of Barbara Harris. She has never before seemed so fully used. The film finishes on her, as it begins. She goes mistily upstairs in pursuit of the enormous diamond that the villains have stolen. Lumley watches her. She seems to be in a trance. Maybe she has got supernatural powers, after all. She brings off a clairvoyant’s coup, though we know more than her lover, does. He is purely delighted by her. A Hitchcock film has seldom had a more pacific ending. —Penelope Gilliatt (The New Yorker, April 19, 1976)

Critics in Alfred Hitchcock’s native country seemed to also enjoy the film. One such example would be this rave review from The Times:

“Seventy-seven last Friday, Alfred Hitchcock has yielded to age none of his mastery as storyteller. He still possesses the supreme gift of suspense, in the sense of sustaining, at every moment, curiosity about what comes next. Because it’s played for light comedy going on farce, Family Plot risks being pigeon-holed as a frolic, a minor work in the old master’s canon. Time, I guess, may well accord it a central place. It has the geometric ingenuity of the later American work, along with the delight in quirky character that marked Hitchcock’s British period.

Derived from a novel by Victor Canning and scripted by Ernest Lehman, it maneuvers its plot into a symmetrical situation of two couples who are at once pursuing and pursued by each other. Barbara Harris (rather like a younger and funnier Shelley Winters) is a fake medium who with her accomplice (Bruce Dern), an out-of-work actor doing a little taxi-work, is after the reward for finding a long-lost heir. The heir (William Devane) has gone from bad to worse: having (as it emerges) incinerated his foster-parents, he is now leading a Jekyll-and-Hyde existence, with his accomplice (Karen Black), and a kidnapper who trades his victims for desirable items of stock for his smart jewelry store. Naturally he mistrusts the intentions of the couple whom he discovers to be tailing him.

This plot is speedily established, with, elegant artifice. Driving away from the seance which has put them on the track of their quarry, Harris and Dern almost run down a sinister figure clad (by the veteran Hollywood designer and loyal Hitchcock collaborator Edith Head) all in black. The figure — Karen Black in a blonde wig — hurries on to the pick-up and then back to her accomplice, a villainous young man with a menacing glint in his teeth. The whole stage is set.

There are Hitchcock set-pieces like the Bishop kidnapped while officiating at a Mass or a chase at a funeral, along the maze-like paths of a graveyard, shot from above; jokey moments of fright like the Bishop’s red cassock leaking like blood from a car trunk; a very familiar Hitchcock nightmare when the nice couple are stranded on a bleak and lonely road, and the killer’s car draws slowly into view around the corner; clues delightedly planted like messages in a treasure hunt.

Yet what is most characteristic and charming in the film is a show-off relaxation, an easy demonstration of how it all should be done. Hitchcock this time builds a thriller without ever showing a killing (the only violent death is an accident, out of sight of the spectator); he makes the relationship of the two couples vibrantly, sexy without so much as showing a bed or a naked elbow. He gives a merry coup de grace to the convention of the car chase by reducing it to slapstick, with Harris clinging inconveniently around Dern’s neck as he struggles to control a brake-less car careering downhill and finishing up with her foot in his face. It’s all a very jolly affair.” —Staff (The Times, August 20, 1976)

Admittedly, praise wasn’t universal. There were a few negative reviews. However, they seemed to be buried in the overwhelming approval of the majority… Well, the critical majority. Audiences seem to have been less enthusiastic.

“Hitchcock had always taken pride in his box-office numbers, yet Family Plot was his least successful picture since The Trouble with Harry, another bent comedy to which the fifty-third Hitchcock bore a fleeting resemblance. Its number twenty-six box office ranking was an embarrassment, and to go out on top – with an audience winner – was one reason behind his seeming iron resolve to make yet one more film.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Actually, the director’s resolve to make another film had less to do with the box-office reception of Family Plot, and more to do with his nature. Alfred Hitchcock was a filmmaker. He was happiest when working on a new project. The next project would have been called, The Short Night. Unfortunately, Alfred Hitchcock’s debilitating health forced him to abandon his work on this new venture.

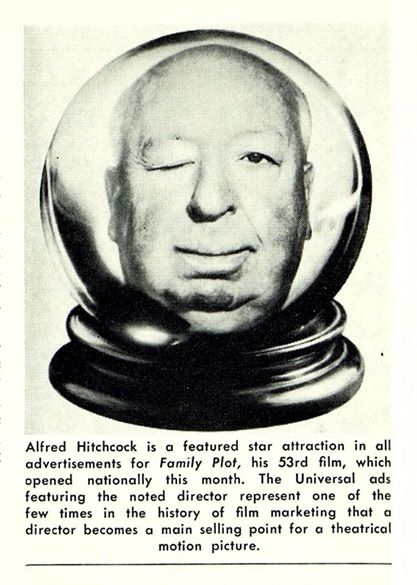

So, in the end, we are left with the wink that so infuriated Ernest Lehman. It doesn’t seem at all inappropriate that Alfred Hitchcock’s swansong should have such a conclusion. After all, Hitchcock had been winking at his audiences for fifty years. What’s more, he has managed to continue winking at us decades after his passing. It was the perfect way to end his final film (even if he didn’t realize it would be his final film). Universal’s publicity department must have agreed because their marketing campaign was centered on a winking Alfred Hitchcock.

[Note: This portion of this review was recycled from one of our earlier articles and is therefore slightly less comprehensive than some of this page’s more recent posts. As a matter of fact, this was the article that pointed us in the proper direction as to how we might approach future articles.]

The Presentation:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

Those who can afford to purchase these Universal titles separately (instead of as part of the boxed set) should absolutely take that route. The two discs are housed in a standard black 2-disc 4K UHD case with an insert sleeve that features film related artwork that is only slightly different from the art used for their older Blu-ray edition of the film. Actually, some fans may prefer the more natural colors used here to the sepia tinted background used for the earlier cover. One wishes that Universal would use the original one sheet designs or at least one of the vintage marketing concepts for the film, but this almost never happens.

At least fans who purchase the individual releases won’t have to fight with the packaging every time they wish to watch the film.

Picture Quality:

4K UHD: 4 of 5 MacGuffins

We will start with the good news… The 4K master used for this transfer is noticeably superior to the lackluster masters used for previous releases. (Actually, this is a bit of understatement as previous masters for this film were fairly awful.) The transfer benefits from the added resolution, but fine detail, clarity, depth, color, and density see a marked improvement that go beyond what one expects when one compares it to the Blu-ray. Unfortunately, this isn’t because this is an amazing transfer. It simply wasn’t treated with the same indifference that was shown previous masters. Grain structure is also improved considerably here, and those who enjoy the format will be pleased to hear this since 4K UHD has a tendency to exacerbate little issues that are more easily ignored on Blu-ray. We want to stress that it is still far from perfect, but it looks much more natural here than on the Blu-ray. Fans will also enjoy the sharper image afforded by the added resolution despite the softer aesthetic provided by the cinematography. One can fault the contrast somewhat as there is some occasional crush evident, and I do not think this is inherited from the cinematography because film handles such things differently (although, the original photography could have made getting the contrast right on this transfer more difficult). Whites do a bit better in this respect as they are bright and crisp without blooming on my screen. Fans will also notice less age-related damage evident in this transfer. There aren’t any encoding issues to complain about this time around either.

HDR offers a noticeable spike in dynamic range and looks okay as long as screens are set up properly. They should really provide a calibration screen on 4K UHD discs like the old Criterion discs did in their earlier days… but I digress. There’s no doubt in my mind that people will raise their eyebrows at some of these statements while thinking “but it is the worst looking transfer in this new batch of Universal titles!” That is true. None of this is meant to imply that it is perfect. I’m merely saying that the master is an improvement upon the ugly master used for the Blu-ray disc…

Blu-ray: 1.5 of 5 MacGuffins

…And Universal has recycled that Blu-ray disc for this release! That’s a major problem. What a complete waste of a perfect opportunity to improve upon an incredibly disappointing transfer! Family Plot needed a Blu-ray upgrade more than any other Hitchcock film in the entire Universal catalogue. There’s really no excuse for not creating a new 1080P Blu-ray master from the newer 4K scan. This is true of all the Universal 4K UHD/Blu-ray Combo editions (with the exception of Psycho which did receive a new Blu-ray master), but none of the titles needed an upgrade more desperately than this film. The new scan could have provided fans with a superior image on the Blu-ray format, but it is clear that Universal cares more about making a quick dollar from their catalogue titles than taking pride in the way that they are presented to viewers. A lot of people still love the Blu-ray format, and many actually prefer it to 4K UHD (and frankly, I can understand their reasoning). This format matters just as much as 4K UHD, and too many studios ignore it when prepping for their combo releases. This is a shame because classic films deserve better. Yes, I am essentially repeating myself. Actually, Family Plot offers a good example of why it matters that they haven’t given the films new Blu-ray masters. This title desperately needed a Blu-ray upgrade, and it could have easily been given one. Universal doesn’t mind milking these Hitchcock titles for all they are worth, but they don’t want to do right by them.

Actually, they should have been embarrassed about this sometimes passable but often ugly looking 1080P AVC encoded transfer. It is difficult to know whether the problems here stem from ineptitude or just good old-fashioned apathy, but it is difficult to forgive the results here. Family Plot has never looked particularly wonderful on home video, but one always hopes that a studio will improve the quality of each subsequent release. Most of these issues are not inherent in the source print either. There might be a slight improvement in detail from the previous DVD releases, but it is nowhere near what one expects from a Blu-ray transfer. Texture has been scrubbed from the image by an excessive use of digital noise reduction, and there are many occasions when haloing is a problem. Darker scenes have been crushed, while colors and contrast are uneven. Grain can be a very beautiful thing and is part of the film aesthetic. However, it is difficult to appreciate it here because it isn’t behaving in a natural manner. This is almost certainly a transfer issue. Finally, there is a bit of film damage that could have been easily fixed if Universal actually put forth a minimal amount of effort to bring this film to high definition. This is Universal’s worst transfer of an Alfred Hitchcock film. The only good news is that the resolution is superior to their DVD editions of the film.

Sound Quality:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

It might not be nearly enough of a consolation to say that the sound transfer doesn’t suffer the same apathetic treatment by Universal (even if it has been recycled from the same 2012 Blu-ray). Both discs use the same 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio track that we have all come to know, but that’s an acceptable decision since it was a faithful and lossless representation of the film’s original audio that exhibited clear dialogue, balanced effects, and a full score by John Williams. This is as good as anyone might expect from a mono mix. Purists shouldn’t have any trouble embracing the track.

Special Features:

3.5 of 5 Stars

One wonders why the excellent press conference for Family Plot wasn’t included in the supplements. The ninety-minute Q & A would have made up for at least some of the disc’s less successful attributes. However, the excellent supplements that were available on previous DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film have been carried over to the UHD disc as well.

Plotting Family Plot — (48:22)

Laurent Bouzereau’s “Plotting Family Plot” isn’t the best of his Hitchcock related documentaries, but it isn’t the worst either. It is superior to the fluff that is produced for most recent home video releases and does manage to give viewers an authentic glimpse into the production of Alfred Hitchcock’s final film. The program even utilizes actual ‘behind the scenes’ footage from the film’s production to illustrate the various interviews with the film’s cast and crew. Participants include Patricia Hitchcock, Howard G. Kazanjian, Bruce Dern, William Devane, Karen Black, Henry Bumstead, John Williams, and Hilton A. Green. It is essential viewing for fans.

Theatrical Trailers — (03:17)

There are two theatrical trailers included, and both of them feature Alfred Hitchcock. The second of the two is probably the best, but it is nice to see both of them included on the disc (even if they are cropped).

Storyboards: The Chase Scene — (09:39)

It is always nice to see storyboards included, and this slide show of the pre-visualization storyboards of the film’s chase sequence is no exception.

Production Photographs — (14:29)

A slide show of production photographs is also included, and they round off the disc nicely.

Final Words:

Family Plot is a pleasant farewell from one of cinema’s greatest “auteurs.” It might not be one of his best efforts, but it is difficult not to have a great time. A lot of cinephiles complain that the film looks like a “made for television movie” (which can be said of most mid-to-low budget studio productions from this period). Most of the more celebrated films from this period were being made on location in a completely different style. It’s also worth mentioning that Universal’s stable of technicians during this time —including Leonard J. South (the cinematographer) — were trained by working one various television productions. Only a time machine could have provided us with a film that looked like the films produced in his heyday.

Meanwhile, Universal’s previous transfers only exacerbate these perceived issues with the film. The new 4K UHD transfer is a marked improvement over previous editions of the film, but it is also the weakest of this new batch of 4K UHD transfers.

Review by: Devon Powell

Source Materials

Bob Thomas (Alfred Hitchcock is 75, Busy Directing New Movie, Anniston Star, August 24, 1975)

Staff (Variety, December 31, 1975)

Family Plot Press Conference (March 23rd, 1976)

Vincent Canby (New York Times, April 10, 1976)

Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun Times, April 12, 1976)

S.K. (The Independent Film Journal, April 14, 1976)

Universal Publicity (The Independent Film Journal, April 14, 1976)

Penelope Gilliatt (The New Yorker, April 19, 1976)

Staff (Hitchcock Lets Stars Play It by Ear, Athens News Courier, June 01, 1976)

Staff (The Times, August 20, 1976)

Donald Spoto (The Art of Alfred Hitchcock, 1976)

John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Laurent Bouzereau (Plotting Family Plot, 2001)

Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Charlotte Chandler (It’s Only a Movie: Alfred Hitchcock — A Personal Biography, 2005)

Reblogged this on Blu-ray Downlow.

One of my favorite Hitchcock films. I watch it every time it is on TCM. Wonderful essay. Re-posted @Trefology