Spine #5

Distributor: Criterion Collection (USA)

Release Date: 08/Apr/ 2014

Region: Region A

Length: 1:40:02

Video: 1080P (MPEG-4, AVC)

Main Audio: Uncompressed French Mono

Subtitles: English

Ratio: 2.34:1

Bitrate: 38.83 Mbps

Notes: This release also includes a DVD disc. Criterion released the film as a Blu-ray only release in 2009 and the title is available on DVD as well.

“I had made The 400 Blows in a state of anxiety, because I was afraid that the film would never be released and that, if it did come out, people would say, ‘After having insulted everyone as a critic, Truffaut should have stayed home!’” —François Truffaut

François Truffaut’s book-length interview with Alfred Hitchcock is the text on which all other writings about the director revolve. This might sound unfair to the countless contributions of other writers to the study of Hitchcock’s work, but it would be very difficult to dispute this claim. By the time Truffaut began his series of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock in the fall of 1962, he had already directed three feature films (The 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player, and Jules and Jim).

Les quatre cents coups (more commonly known as The 400 Blows in English speaking territories) was Truffaut’s debut feature film. It helped establish the French New Wave and was met with an amazing amount of critical praise upon its release. By all accounts, the director was rather surprised at the success of these early New Wave films.

“I don’t know if there was actually a plan behind the New Wave, but as far as I was concerned, it never occurred to me to revolutionize the cinema or to express myself differently from previous filmmakers. I always thought that the cinema was just fine, except for the fact that it lacked sincerity. I’d do the same thing others were doing, but better.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

The sincerity that Truffaut was able to capture in The 400 Blows is one of the film’s major triumphs and what sets it apart from other films that focused on childhood. Truffaut had recently finished a short film that centered on children and was not completely happy with the finished product. As a matter of fact, The 400 Blows was originally intended as one in a series of shorts focusing on children.

“My first real film, in 1957, was Les Mistons — The Mischief Makersin English. It had the advantage of telling a story, which was not common practice for short films in those days! It also gave me the opportunity to start working with actors…

…I saw it as the first of a series of sketches. It was easier at the time, and would be even now, to find money for three or four different short films than to find enough financial support for a feature film. So I planned to do a series of sketches with the common thread of childhood. I had five or six stories from which I could choose. I started with Les Mistons because it was the easiest to shoot.

When it was finished, I wasn’t completely satisfied because the film was a little too literary. Let me explain: Les Mistons is the story of five children who spy on young lovers. And I noticed, in directing these children; that they had no interest in the girl, who was played by Gérard Blain’s wife, Bernadette Lafont; the boys weren’t jealous of Blain himself, either. So I had them do contrived things to make them appear jealous, and later this annoyed me. I told myself that I’d film with children again, but next time I would have them be truer to life and use as little fiction as possible…

… When I was shooting Les Mistons, The 400 Blows already existed in my mind in the form of a short film, which was titled Antoine Runs Away…

… I was disappointed by Les Mistons, or at least by its brevity. You see, I had come to reject the sort of film made up of several skits or sketches. So I preferred to leave Les Mistons as a short and to take my chances with a full-length film by spinning out the story of Antoine Runs Away. Of the five or six stories I had already outlined, this was my favorite, and it became The 400 Blows.

Antoine Runs Away was a twenty-minute sketch about a boy who plays hooky and, having no note to hand in as an excuse, makes up the story that his mother has died. His lie having been discovered, he does not dare go home and spends the night outdoors. I decided to develop this story with the help of Marcel Moussy, at the time a television writer whose shows for a program called If It Was You were very realistic and very successful. They always dealt with family or social problems. Moussy and I added to the beginning and the end of Antoine’s story until it became a kind of chronicle of a boy’s thirteenth year—of the awkward early teenaged years.

In fact, The 400 Blows became a rather pessimistic film. I can’t really say what the theme is—there is none, perhaps—but one central idea was to depict early adolescence as a difficult time of passage and not to fall into the usual nostalgia about “the good old days,” the salad days of youth – because, for me in any event, childhood is a series of painful memories. Now, when I feel blue, I tell myself, ‘I’m an adult. I do as I please’ and that cheers me up right away. But then, childhood seemed like such a hard phase of life; you’re not allowed to make any mistakes. Making a mistake is a crime: you break a plate by mistake and it’s a real offense. That was my approach in The 400 Blows, using a relatively flexible script to leave room for improvisation, mostly provided by the actors. I was very happy in this respect with Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine, who was quite different from the original character I had imagined.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

Truffaut was not afraid to change his original conception in order to enhance the film’s authenticity and believed that casting Léaud improved his vision.

“I didn’t like the idea of finding a kid on the street and asking his parents, ‘Would you let him make a movie with me?’ For this first feature film of mine about children, I wanted the children to be willing — both the children and their parents. So I used the ad to get them to come to a studio near the Champs-Elysées, where I was doing 16-mm screen tests every Thursday. I saw a number of boys, one of whom was Jean-Pierre Léaud. He was more interesting than all the rest, more intense, more frantic even. He really, really wanted the part, and I think that touched me. I could feel during the shoot that the story improved, that the film became better than the screenplay, thanks to him.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

The screenplay itself was already built around the idea of presenting events honestly from a child’s perspective. As a matter of fact, the project was a personal one for Truffaut.

“All I can say is that nothing in it is invented. What didn’t happen to me personally – happened to people I know – to boys my age and even to people that I had read about in the papers. Nothing in The 400 Blows is pure fiction, then, but neither is the film a wholly autobiographical work…

…As for my method of writing, I started making “script sheets” when I began work on The 400 Blows. School: various gags at school. Home: some gags at home. Street: a few gags in the street. I think everyone works in this way, at least on some films. You certainly do it for comedies, and you can even do it for dramas. And this material, in my case, was often based on memories. I realized that you can really exercise your memory where the past is concerned. I had found a class photo, for example, one in the classic pose with all the pupils lined up. The first time I looked at that picture, I could remember the names of only two friends. But by looking at it for an hour each morning over a period of several days, I remembered all my classmates’ names, their parents’ jobs, and where everybody lived.

It was around this time that I met Moussy and asked him if he’d like to work with me on the script of The 400 Blows. Since I myself had played hooky quite a bit, all of Antoine’s problems with fake notes, forged signatures, bad report cards—all of these I knew by heart, of course. The movies to which we truants went started at around ten in the morning; there were several theaters in Paris that opened at such an early hour. And their clientele was made up almost exclusively of schoolchildren! But you couldn’t go with your schoolbag, because it would make you look suspicious. So we hid our bags behind the door of the theater. Two of these movie houses faced each other: the Cinéac-Italiens and the New York. Each morning around nine-forty-five, there would be fifty or sixty children waiting outside to get in. And the first theater to open would get all the business because we were anxious to hide. We felt awfully exposed out there in the middle of all that.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

While shooting the picture, the director occasionally found himself unsure how to approach a scene.

“…Antoine, who told the teacher that his mother had died to avoid having to hand in a note for his absence, and who is found out in the afternoon when his mother comes to the school—decides never to return home. And after school, he talks with his young friend about his plans. This was quite difficult dialogue to do because it wasn’t natural. These words weren’t something a child would normally say; I’m very realistic, and such moments, as originally written, went against the—or my—grain. It was hard, therefore, to find the right stance with which to direct Jean-Pierre Léaud in this scene. For some reason, the situation reminded me of a scene in The Human Beast, where Jean Gabin, as Jacques Lantier, returns at the very end of the movie. He comes back to his locomotive the morning after killing Simone Simon’s character and he has to explain to the other conductor, played by Julien Carette, that he killed this woman. Renoir directed Gabin marvelously here, precisely by using the hallmark of his cinematic style: its utter casualness or offhandedness. Gabin says, ‘It’s horrible. I killed her. I loved her. I’ll never see her again. I’ll never be by her side.’ He said all this very softly, very simply. And I used my memory of Gabin’s performance to direct Léaud, who did his own scene exactly like Gabin’s.

That was a tough scene. It was easier to coach Léaud in the scene where he goes to school without a note after a three-day absence and decides to say his mother died. In this instance there wasn’t any question of someone’s directorial influence on me but only of my own directorial instinct. We don’t know that Antoine has decided to tell this lie, only that he’ll say something big. Of course, he could use a number of ways to say his mother had died. He could be shifty or sad or whatever. I decided the boy should give the impression that he doesn’t want to tell the lie. That he doesn’t dare say it but that the teacher pushes him to do so. The teacher asks, ‘Where’s your note?’ and the child replies, ‘It’s my mother, sir.’ The teacher inquires, ‘Your mother? What about her?’ It’s only because the teacher badgers him that Antoine suddenly decides to fight back and say, ‘She’s dead!’ I told Léaud, ‘You say, ‘She’s dead!’ but you think in your head, ‘She’s dead! What do you say to that?’ He doesn’t say this but he thinks it, and that gives him the exact look and tone of voice I wanted—even the upturned head. There’s a lie you can use only once!

Let me give you another example, returning once again to the issue of directorial influence—this time of someone other than Renoir. If in The 400 Blows, I had filmed the father coming to the classroom and slapping his son after the boy returned to school and said his mother was dead, then I’d have had problems editing because I would have wanted fast action here and could have gotten that only with a lot of cutting. But the rest of the film was just a matter of capturing a lot of situations without an excessive amount of cutting. So I knew I’d have to create the drama in this scene within the frame itself, with little or no cutting, and I thought of Alfred Hitchcock. Otherwise I had no point of reference; I had no idea how to edit the scene in order to create the intensity I wanted. I knew now that I had to show the headmaster, then there’s a knock on the door, the boy senses it’s about him, and next you see the mother. I told the actress Claire Maurier that, instead of scanning the classroom for her son, as might be natural since she had never been to the school before, she was to look right away in the direction of Antoine’s desk. I knew that this would create the dramatic effect I was looking for, and not the reality of her searching for her son’s face amidst a sea of other young faces.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

One of the most discussed scenes in the film is so-called interview scene (a scene where Antoine is interviewed by a psychologist). The scene was shot in an unorthodox manner in order to achieve a greater sense of realism.

“The scene had to be improvised. I began by filming a 16mm version in which I asked Léaud questions, and he replied spontaneously. When we reached this scene in the actual shooting, I decided that what we were getting was inferior to my 16mm trial, which had been so fresh. To regain that freshness, I adopted a peculiar method of working. I told everyone to leave the set except Léaud and the cameraman. Then I read out the scripted psychologist’s questions, asking Léaud to answer on the spot with whatever came into his mind. During post-synchronization, I had my questions read over by the actress who played the psychologist. However, since I wanted a woman with a very soft voice, who by this time was very pregnant and therefore reluctant to be filmed, I had only her voice but not her person, so you hear and don’t see her… Since when I originally filmed the scene, I had banished the script girl and clapper boy from the set, I had no one to mark the precise moments of cutting and thus had to use the relatively imprecise dissolve to mark all connections between the pieces of Léaud ‘s response that I decided to retain.” —François Truffaut (Encountering Directors, September 1 & 3, 1970)

The recorded sound contributed to the scene in other ways as well.

“The 400 Blows was shot almost entirely without sound. It was dubbed afterwards, except for one scene, where the psychologist questions Antoine. If this scene got so much notice, it’s not just because Léaud’s performance was so realistic; it’s also because this was the only scene we shot with live sound. The shooting of such a scene, as you might guess, is heavily influenced by television. Although I believe TV is misguided when it attempts to compete with the cinema by trying to handle poetry or fantasy, it’s in its element when it questions someone and lets him explain himself. This scene from The 400 Blows was definitely done with television in mind… Aside from this scene with the psychologist, the dubbing worked rather well, because children are easily dubbed, and Jean-Pierre Léaud is dubbed so well you can’t tell. With the parents in the film, the post-synchronization is not so good.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

Also contributing to the films aura of reality is the location work.

“…We filmed in real locations. We found a tiny apartment on Rue Caulaincourt in Paris, but I was afraid that my cameraman, Henri Decaë, wouldn’t want to film there. I showed it to him and he nonetheless accepted, knowing the numerous problems he would face. For example, when we wanted to show the father, the mother, and the boy around the dinner table, Decaë had to sit on the windowsill, on the sixth floor, with the whole crew waiting outside on the stairs. Things like that happened all the time. I don’t like studios, I have to say; I overwhelmingly prefer to shoot on location.” —François Truffaut (Action! Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran)

Truffaut’s fondness for location work is in harmony with his tendency to embrace what many might consider problems. He was able to turn problems into artistic statements. The poignant final freeze frame that ends this classic has been discussed at length by countless scholars and critics, but it was surprisingly a matter of necessity.

“The final freeze was an accident. I told Léaud to look into the camera. He did, but quickly turned his eyes away. Since I wanted that brief look he gave me the moment before he turned, I had no choice but to hold on it: hence the freeze.” —François Truffaut (Encountering Directors, September 1 & 3, 1970)

There have been many interpretations of the shot, but everyone seems to acknowledge its power. This effect ends the film on an extremely powerful note and cements the moment in the viewer’s heart and mind.

The entire film works on a very human level and critics and audiences alike have lauded Truffaut’s debut since it was released in 1959. Bosley Crowther’s review was typical of the praise that the film received.

“Let it be noted without contention that the crest of the flow of recent films from the ‘new wave’ of young French directors hit these shores yesterday with the arrival at the Fine Arts Theatre of The 400 Blows (Les Quatre Cents Coups) of Françcois Truffaut.

Not since the 1952 arrival of René Clement’s Forbidden Games, with which this extraordinary little picture of M. Truffaut most interestingly compares, have we had from France a cinema that so brilliantly and strikingly reveals the explosion of a fresh creative talent in the directorial field.

Amazingly, this vigorous effort is the first feature film of M. Truffaut, who had previously been (of all things!) the movie critic for a French magazine. (A short film of his, The Mischief Makers, was shown here at the Little Carnegie some months back.) But, for all his professional inexperience and his youthfulness (27 years), M. Truffaut has here turned out a picture that might be termed a small masterpiece.

The striking distinctions of it are the clarity and honesty with which it presents a moving story of the troubles of a 12-year-old boy. Where previous films on similar subjects have been fatted and fictionalized with all sorts of adult misconceptions and sentimentalities, this is a smashingly convincing demonstration on the level of the boy—cool, firm and realistic, without a false note or a trace of goo.

And yet, in its frank examination of the life of this tough Parisian kid as he moves through the lonely stages of disintegration at home and at school, it offers an overwhelming insight into the emotional confusion of the lad and a truly heartbreaking awareness of his unspoken agonies.

It is said that this film, which M. Truffaut has written, directed and produced, is autobiographical. That may well explain the feeling of intimate occurrence that is packed into all its candid scenes. From the introductory sequence, which takes the viewer in an automobile through middle-class quarters of Paris in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, while a curiously rollicking yet plaintive musical score is played, one gets a profound impression of being personally involved—a hard-by observer, if not participant, in the small joys and sorrows of the boy.

Because of the stunningly literal and factual camera style of M. Truffaut, as well as his clear and sympathetic understanding of the matter he explores, one feels close enough to the parents to cry out to them their cruel mistakes or to shake an obtuse and dull schoolteacher into an awareness of the wrong he does bright boys.

Eagerness makes us want to tell you of countless charming things in this film, little bits of un-pushed communication that spin a fine web of sympathy—little things that tell you volumes about the tough, courageous nature of the boy, his rugged, sometimes ruthless, self-possession and his poignant naïveté. They are subtle, often droll. Also we would like to note a lot about the pathos of the parents and the social incompetence of the kind of school that is here represented and is obviously hated and condemned by M. Truffaut.

But space prohibits expansion, other than to say that the compound is not only moving but also tremendously meaningful. When the lad finally says of his parents, ‘They didn’t always tell the truth,’ there is spoken the most profound summation of the problem of the wayward child today.

Words cannot state simply how fine is Jean-Pierre Léaud in the role of the boy — how implacably deadpanned yet expressive, how apparently relaxed yet tense, how beautifully positive in his movement, like a pint-sized Jean Gabin. Out of this brand new youngster, M. Truffaut has elicited a performance that will live as a delightful, provoking and heartbreaking monument to a boy…

…Here is a picture that encourages an exciting refreshment of faith in films.” —The New York Times (November 17, 1959)

One cannot help but notice Crowther’s comparison of Jean-Pierre Léaud with Jean Gabin (since the director directed the young actor based on one of Gabin’s performances). All of the performances in the film were applauded in the media. The few criticisms that the film received seemed to be related to the technical aspects of the production and these were tempered with enthusiasm for nearly every other aspect of the film.

Critical opinion hasn’t waned over the years. Roger Ebert even included the film in his list of “Great Movies.”

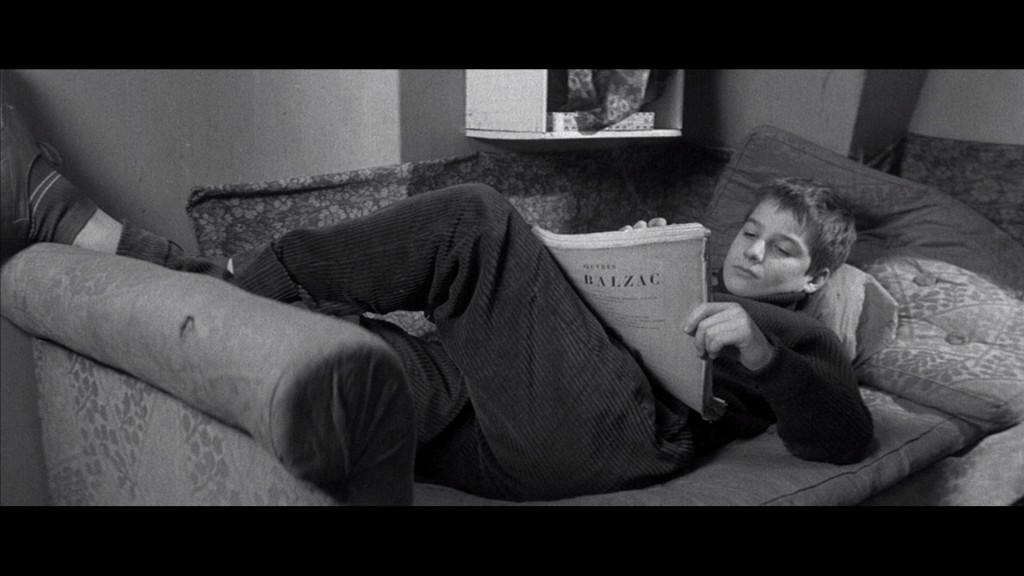

“Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) is one of the most intensely touching stories ever made about a young adolescent. Inspired by Truffaut’s own early life, it shows a resourceful boy growing up in Paris and apparently dashing headlong into a life of crime. Adults see him as a troublemaker. We are allowed to share some of his private moments, as when he lights a candle before a little shrine to Balzac in his bedroom. The film’s famous final shot, a zoom in to a freeze frame, shows him looking directly into the camera. He has just run away from a house of detention, and is on the beach, caught between land and water, between past and future. It is the first time he has seen the sea…

…Little is done in the film for pure effect. Everything adds to the impact of the final shot…” —Chicago Sun Times (August 8, 1999)

Like many of Ebert’s reviews, most of the text is devoted to a synopsis of the film’s story. His five star rating offers the clearest statement of his feelings towards the classic. Sometimes it is enough to say that a film is essential and leave it at that.

The Presentation:

4.5 of 5 MacGuffins

The Blu-ray and DVD discs are housed in the clear case that has become the standard for The Criterion Collection. The iconic artwork that decorates the case should please any cinema enthusiast. An added bonus is the wonderful fold out pamphlet featuring photos from the film and an essay by Annette Insdorf. The animated menus are equally attractive and feature the young Antoine running away from reform school.

Picture Quality:

4.5 of 5 MacGuffins

Criterion’s 1080p transfer is simply beautiful. Blu-ray discs have the ability to make black and white films look truly amazing and this disc provides adequate proof of this. Blacks are rich and whites are clean and natural here, and contrast levels seem to be perfect. Clarity and detail are impressive and showcase textures that have not been seen on previous home video formats. There seems to be little to no perceivable DNR manipulation present, which means that Criterion’s restoration efforts were meticulously handled. There is a layer of grain that beautifully mirrors its celluloid source while providing a more cinematic experience. This seems to accurately reflect the film’s source elements and the problems one might find in the transfer are likely evident in the source.

Sound Quality:

4.5 of 5 MacGuffins

The uncompressed French Mono track is impressive and seems to have benefited from Criterion’s restoration efforts. Dialogue is consistently clear and the music sounds full and clear with little to no distortion. The included English subtitles seem to provide a good translation of the French dialogue. There is very little here to complain about.

Special Features:

4.5 of 5 MacGuffins

Audio Commentary by Brian Stonehill

In this highly informative commentary, Brian Stonehill discusses the film from a number of angles, including the cultural impact that the film had upon its release and where the film stands in the context of his career. The film is somewhat dry and scholarly, which should please some and disappoint others. However, those who listen will be rewarded.

Audio Commentary by Robert Lachenay

Robert Lachenay’s commentary is more personal and anecdotal in nature. While Lachenay speaks in his native language, English subtitles are available for those of us who need them. The more personal approach makes for an entertaining track that is rich in information and will increase the viewer’s understanding and appreciation of this classic film.

Rare Audition Footage of Jean-Pierre Léaud, Patrick Auffay, and Richard Kanayan— (06:24)

Criterion has including some priceless 16mm audition footage. This is not only valuable as an entertaining curiosity, but has the added value of shedding light on Truffaut’s approach to choosing his actors.

Newsreel Footage of Jean-Pierre Léaud in Cannes — (05:51)

This highly enjoyable footage of Léaud enjoying the spotlight at Cannes gives viewers a glimpse of how well the film was received.

Cineastes de Notre Temps (1965) — (22:27)

Truffaut, Léaud, Remy Albert, and Claude de Givray discuss Truffaut and his success, often focusing on The 400 Blows. The program was produced for French television and includes English subtitles. This relatively brief program is rich in information and is a welcome and valuable addition to the disc.

Cinépanorama Interview — (06:51)

François Truffaut answers questions about The 400 Blows after the film was awarded by the New York Film Critics. The interview is quite brief but offers some interesting information. It is a nice companion piece to the Cineastes de Notre Temps program.

Theatrical Trailer— (03:47)

This Theatrical Trailer is interesting mostly because it is a trailer for a foreign film and this sets it apart from other trailers. It is a welcome addition to this wonderful set.

Final Words:

The 400 Blows is one of the cinema’s essential classics, and Criterion has given the film a release worthy of the title. The sound and picture transfers are both wonderful and the supplementary material is illuminating and enjoyable. Who could ask for anything more?

Additional Note:

François Truffaut and Alfred Hitchcock actually discussed The 400 Blows during their legendary interview, but this part of the conversation was not included in the published book. The audio from this part of their conversation can be heard here (skip to 11.37):

what a great film. here’s my review of it at A World of Film http://aworldoffilm.com/2013/12/28/les-quatre-cents-coups-the-400-blows-1959-francois-truffant-niall-mcardle/

A fabulous presentation here, and one that has a particular interest to me at this time after having seen this New Wave landmark and film masterpiece at Manhattan’s Film Forum on Sunday as the first feature screened for the two week ‘Tout Truffaut’ Festival I am actively attending. Yes, like so many other cinema fans I have seen the film many times over the years, and in my case I fondly recollect it was the very first foreign-language film I ever saw as an impressionable teenager. This deeply affecting study of a troubled adolescent retains its universality, and as you note that unforgettable freeze-frame on the beach is one of the cinema’s most iconic moments. I was thrilled to escort my 16 year old son Sammy and my 14 year-old son Danny to the screening, and both were moved and motivated to talk about the film in the car on the way home. As always, Jean Constantin’s lyrical score enriches this personal experience, and I am still humming it and playing by CD days later. Henri Decae’s evocative black and white shows Paris in a unique way, stressing as it does a more alienating context. It remains Truffaut’s greatest film even after he followed it up with 20 some odd others before his tragic death at only 52 in 1984. Sure, JULES AND JIM, TWO ENGLISH GIRLS and THE STORY OF ADELE H are masterworks too (and high marks must also go to THE LAST METRO, STOLEN KISSES, THE WILD CHILD, SMALL CHANGE and THE GREEN ROOM) but there is a spontaneity and wistfulness in his first film that he never quite equaled, and it remains proof parcel for anyone trying to diminish Truffaut’s status as a French New Wave heavyweight. Anyway, fantastic post here.

The 400 Blows is a masterpiece. It’s one of my favorite coming-of-age films. Nice review!

It is one of my favorites as well. 🙂 Thanks for visiting.

I knew that your posts about Hitchcock Blu-rays were in-depth, but you managed similar results with this review as well. I recently saw this film and it became an instant favorite. It is good to see that it is getting a decent Blu-ray release. It is on my “to buy” list now!

Like button playing up but I like! It’s years since I’ve seen this so I must rectify that.

I have never seen this film before. Some of the screenshots that you posted are pretty cool and peak my interest.

Hey, I want you to have this award! Check out http://jmountswritteninblood.com/2014/04/22/i-got-the-liebster-award-and-i-want-to-share-it-with-11-bloggers/ for details.

Haven’t seen “The 400 Blows” in quite some time. Definitely due for a re-screening. Great blog you have here. I’ve attached a link to it on mine. That way, I can take my time reading through the staggering number of posts. Great work! Makes my “North By Northwest” write-up look like it was written on a napkin.

Thanks for the kind words and thanks so much for reading. 🙂

Teeritz, I love your blog; it has a great look and a great feel (and a great variety of topics). awesome cover photo

@ AH Master, thanks very much!

@ Niall McArdle, thank- you too!