Distributor: Universal Studios

Release Date: November 05, 2013

Region: Region Free

Length: 143 min

Video: 1080P (VC-1)

Main Audio: English Mono DTS-HD Master Audio

Subtitles: English SDH, French, Spanish

Ratio: 1.85:1

Notes: This title has had a number of DVD releases and is also available on Blu-ray as part of a boxed set entitled The Masterpiece Collection. The transfer used for the boxed set is the same one that is included here and the disc includes the same special features. The artwork on the actual disc is the only thing different about this release.

“Well, to me, logic is dull… Of course, if you boil things down, everything must be logical… And there are complaints, consequently, about being too… you know, I’ve even heard some people say that doing a film like Topaz, which was a bestseller, and it deals with espionage during the [Cuban] missile crisis, where I’m not permitted, by the mere facts themselves, to deviate.” –Alfred Hitchcock (Speculation – Channel 28, 1969)

There is a lot of talk about Alfred Hitchcock’s “creative decline.” Unfortunately, it wasn’t really a decline at all. It was a forced retreat. The director was still working under the tight reigns of Universal in 1969. The studio had set the director up in a cozy bungalow and had made him a very rich man. Unfortunately, they had also taken away his creative liberty and created an atmosphere that nurtured his creative decline (or what people perceive to be his creative decline). Their control of his creative ventures had driven his self confidence into exile.

Before the director made Torn Curtain, the studio had blocked one of the director’s dream projects; a new take on J.M. Barrie’s Mary Rose. After shooting Torn Curtain, Hitchcock had become excited about re-inventing the Hitchcock picture. He called his new project Kaleidoscope. (The project was later called Frenzy. However, it shouldn’t be confused with the 1972 film.)

Kaleidoscope was to be shot on actual locations using natural light, a handheld camera, and unknown actors. The script was shocking and extremely controversial. Hitchcock usually allowed audiences to relate to a likeable protagonist, but this new project would focus on the exploits of an attractive but vulnerable serial killer. Unfortunately, the script’s explicit and unflinching violence disturbed the suits at Universal. In “Hitchcock Lost and Found,” Alain Kerzoncuf and Charles Barr summed up the situation in a single paragraph.

“…This new freedom of technique and of sexual explicitness led Hitchcock, with the help primarily of [Benn] Levy, and later others, to develop plans for the New York sex-murderer story, sadly blocked by Universal, that were bolder than anything ultimately realized in the London Frenzy. His experience with Universal in some ways echoed his experience with BIP: all sweetness and light to start with, but then frustratingly restrictive.” – Alain Kerzoncuf and Charles Barr (Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films)

Frankly, Hitchcock was at his best when he was allowed complete control over his projects. When one looks at his early years at British International Pictures (where he was reduced to making projects that were assigned to him) and compares them with his films made with Gaumont/Gainsborough (where he was allowed to choose his own projects, and have control over them), it becomes clear that Alfred Hitchcock worked best when he worked in absolute freedom. His years at Universal offer further proof of this when one compares them with his years at Paramount (where he was usually given creative control over his own output).

In any case, it was felt that the avant-garde project didn’t have any commercial potential, and Hitchcock was convinced that he should abandon the project. If this had happened ten years earlier, he would have probably made the film with his own money (as he did with Psycho). Unfortunately, he agreed to drop the project for a more commercial venture… but what commercial venture?

“The obvious answer would come from Universal: what properties did they own which might be turned to his purposes? A rummage through the books and plays they had acquired came up with nothing very promising except Leon Uris’s sprawling and complicated espionage novel, Topaz. It was not ideal, and his previous essay in espionage and Iron Curtain politics had not been too happy. But it was better than nothing, and Hitch set to work with a will. Uris himself was involved in writing the screenplay, but Hitch did not see how he could use this, and was forced to go into production with nothing like his usual preparation… He was already in London picking locations when he decided to throw out the script he had, and cabled Sam Taylor, who had written Vertigo for him…” -John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock)

Universal was to blame for pushing an unwritten project into production in order to finish in time for a September release. Samuel Taylor agreed to re-write the script, but it was still being prepared when the film went into production.

“Topaz was not at all a typical Hitchcock production. We were writing scenes the night before filming, which Hitchcock didn’t like at all. The studio really put him in an awkward position.” –Samuel Taylor (as quoted in Hitchcock’s Notebooks by Dan Auiler)

Filming certainly suffered from the rushed pre-production process, and the trouble would continue through post production. When test audiences hated the film’s original duel ending, Hitchcock shot an alternative ending that showed Jacques Granville boarding a plane to Moscow while André and Nicole Devereaux board a plane for Washington D.C. This ending raised a few eyebrows because Granville went unpunished, and it was felt that the French authorities would not accept this ending for a French release.

To prepare for trouble with the French authorities, Hitchcock prepared a third ending utilizing already shot footage that suggests that Granville goes home and commits suicide. The debate about which of the latter two endings should be used continued until it was finally decided to use different endings for different markets. However, production records suggest that Alfred Hitchcock preferred the Airport ending that shows Granville leaving for Moscow. He claimed that it was more true to life, and he even suggested hiding the suicide ending away so that it wouldn’t be used.

It is no wonder that Topaz is considered by many to be the director’s weakest American effort. The film was a box office failure, and failed to earn back its $4,000,000 budget. However, the film had some incredible moments that illustrate Alfred Hitchcock’s cinematic brilliance (such as Juanita de Cordoba’s exquisite murder, and the excellent Pietà influenced post torture interrogation that lead to Juanita’s murder), and there were a number of critics that enjoyed Topaz.

The review that was published in The Independent Film Journal was particularly kind.

“…The director is up to his old tricks, but they are still very good ones. An effective cast of mostly foreign players and a nicely complicated plot make the film thoroughly absorbing. Solid Box-office.

There will undoubtedly be those movie buffs who will argue that Alfred Hitchcock’s Topaz is an echo chamber, [and] that everything in it has been done before by the master, and better. But after the malnutritious Marnie and Torn Curtain, it is a pleasure to find the director working with a densely plotted story-line. You have to keep on your toes during Topaz and that’s what makes it so enjoyable. The film is a thoroughly absorbing work, but an abrupt ending, meant probably to be ironic, has the effect of pulling the carpet out from under the viewer. As a commercial entry, the box office potential for Topaz is very strong; the Hitchcock name alone would be a crowd-puller, but this time he is also working with a pre-sold property; the Leon Uris novel his film was based on was an international best seller.

Topaz begins beautifully, and silently, with a sequence depicting a Russian KGB official, his wife and teenage daughter attempting to flee Copenhagen and defect to the Americans. They are trailed by Russian agents through a porcelain factory and the Den Permanente department store…

…Samuel Taylor’s screenplay has more than its share of cliché lines, but it also has its share of very amusing ones. It gets the characters on and off, and globe-trots efficiently enough, but two omissions are disturbing. We are never told just why Devereaux would risk everything for the American agent, and the arrival of Devereaux’s wife (Dany Robin) at the hide-out of Jacques Granville (Michel Piccoli), suspected of being a member of the Topaz ring is a surprise, but an unexplained one.

In telling the complicated story, Hitchcock has supplied his usual touches. For a tortured woman’s inaudible whisper the camera rushes in to hear; Juanita’s murder is recorded by an overhead shot, and as her corpse collapses, the deep purple dress spreads out like blossoms of a flower; a seagull flying with an unusually large piece of bread in its beak giving away the fact there must be snooping picnickers nearby. Cameras glide up and down staircases, swoop onto mirrored reflections of the enemy’s face.

Seeing things rather than hearing them, has always been a favorite device of Hitchcock’s (Rear Window was practically devoted to it) and in Topaz it is again used. Instructions between Devereaux and his contact take place behind a florist’s refrigerator glass door; an important transaction at the Hotel Teresa is shown from across the street; and in a spacious conference room, the camera way up amidst the chandeliers, we watch as various consuls shift into groups, isolating themselves from the suspected traitor.

In the past Hitchcock has been hampered by casting his films with an eye toward box-office (Jane Wyman in Stage Fright, Julie Andrews in Torn Curtain, to name two), but in Topaz he has selected his players, mostly foreign actors, without using any “names.” The choices have been excellent ones, especially Frederick Stafford as Devereaux and the great looking Karin Dor as the doomed Juanita.” -The Independent Film Journal (December 9, 1969)

Vincent Canby went even further in his praise for the film. His review in the New York Times was titled, “Topaz: Alfred Hitchcock at His Best.”

“It’s perfectly apparent from its opening sequence that no one except Alfred Hitchcock, the wise, round, supremely confident storyteller, is in charge of Topaz… Topaz, the code name for a Russian spy ring within the French Government, is the film adaptation of the Leon Uris novel, which itself was based on a real-life espionage scandal that kept both sides of the Atlantic busy in 1962.

Hitchcock sets his scene in a first act that dramatizes the defection of a high Soviet intelligence officer to C.I.A. officials in Copenhagen. The sequence, which lasts approximately 10 minutes and uses only a minimum of dialogue, is virtuoso Hitchcock, beginning with a dazzling, single-take pan shot outside the Soviet Embassy, then detailing the flight, pursuit through, among other things, a ceramics factory and the final safe arrival of the irritable Soviet official and his family aboard an American plane headed for Wiesbaden. The Russian’s only comment to the proud C.I.A. man: “We would have done it better.”

Topaz is not a conventional Hitchcock film. It’s rather too leisurely and the machinations of the plot rather too convoluted to be easily summed up in anything except a very loose sentence. Being pressed, I’d say that it’s about espionage as a kind of game, set in Washington, Havana and Paris at the time of the Cuban missile crisis, involving a number of dedicated people in acts of courage, sacrifice and death, after which the survivors find themselves pretty much where they started, except that they are older, tired and a little less capable of being happy.

Topaz is, however, quite pure Hitchcock, a movie of beautifully composed sequences, full of surface tensions, ironies, absurdities (some hungry seagulls blow the cover of two Allied agents), as well as of odd references to things such as Michaelangelo’s “Pieta,” only it’s not a Mother holding her dead Son, but a middle-aged Cuban wife holding her dead husband, after they’ve been tortured in a Castro prison.

Hitchcock, who can barely tolerate actors, has been especially self-indulgent in the casting of Topaz. The film has no one on the order of James Stewart or Cary Grant on which to depend, although it does use some fine character actors (Michel Piccoli, Phillipe Noiret) in small roles. Most of its performers are, if not entirely unknown, so completely subordinate to their roles that they seem, perhaps unfairly, quite forgettable…

…The people one remembers are those who are employed for the effect of their looks (John Vernon as a bearded Castro aide with brilliant blue eyes, Carlos Rivas as his bodyguard, a Cuban with remarkably red hair), or who are bequeathed vivid images by the narrative (Karin Dor as a beautiful anti-Castro Cuban who is shot for her efforts and collapses onto a marble floor, her body framed by the brilliant purple of her dress).

The star of Topaz is Hitchcock, who, except for his brief, signature appearance, remains just off-screen, manipulating our emotions as well as our memories of so many other Hitchcock films, including Foreign Correspondent, Saboteur and Torn Curtain, all inferior to Topaz. This is a movie of superb sequences that lead from a magnificent Virginia mansion to the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, from an extraordinarily well-stocked Cuban hacienda to a small, claustrophobic, upstairs dining room in a Paris restaurant. Even architecture is important.

It’s also a movie of classic Hitchcock effects. Exposition may be gotten across by being presented either as gossip or as incidental, post-coital small talk. Conversations are often seen — but not heard — through glass doors. A Cuban government minister, staying at the Theresa, finds a misplaced state document being used as a hamburger napkin.

The film is so free of contemporary cinematic clichés, so reassuring in its choice of familiar espionage gadgetry (remote control cameras, Geiger counters), that it tends to look extremely conservative, politically. Topaz, however, is really above such things. It uses politics the way Hitchcock uses actors — for its own ends, without making any real commitments to it. Topaz is not only most entertaining. It is, like so many Hitchcock films, a cautionary fable by one of the most moral cynics of our time.” –Vincent Canby (New York Times, December 20, 1969)

Even Variety published a review that wasn’t completely negative (though it did seem to fall somewhere between the two extremes).

“Topaz tends to move more solidly and less infectiously than many of Alfred Hitchcock’s best remembered [pictures]. Yet Hitchcock brings in a full quota of twists and tingling moments…” -Variety (December 31, 1968)

This praise is probably rather surprising to contemporary audiences and critics. Today, opinion tends to lean almost universally in the opposite direction. In fact, there were critics that were less than enthusiastic about Topaz upon the film’s release. As a matter of fact, John Russell Taylor (Alfred Hitchcock’s official biographer) wrote a review was especially negative.

“Hitchcock, like all major film directors, has made his share of bad films. But never, I think, one which was so generally flat, undistinguished, and lacking in any sign of positive interest or involvement on his part.” -John Russell Taylor (The Times, November 6, 1969)

Richard Corliss wrote a review that was more of a diatribe against auteur theory than an essay about the merits and weaknesses of Topaz. The article had a number of digressions (which have been omitted here) that reveal a certain bias against Hitchcock and the popular opinion that he is an auteur. When he finally gets around to discussing Topaz, it isn’t surprising to discover that his words usually aren’t very kind.

“…Hitchcock will often settle for a mediocre script and indifferent actors simply to play with the emotions of an audience. At his best, Hitchcock is very good — not great…

…Hitchcock, as Sarris has said of Nicholas Ray, “is not the greatest director who ever lived; nor is he a Hollywood hack.” He is neither the Shakespeare of film, as Sarris and Robin Wood state, nor its Shad-well, as Pauline Kael might want us to believe. And Topaz is neither the quintessence of Hitchcockian cinema, nor an aimless, repetitive exercise. Its delights and disappointments are more worthy of analysis than of hagiographies or captious dismissals. Topaz does lack, say, the cohesion and sustained suspense — and, frankly, the performances — of last year’s NBA Championship series between that aging but proud, quite Hawksian group, The Boston Celtics, and the Los Angeles Lakers, an aggressive, fiercely talented quintet of individuals. But the movie has moments — minutes, sequences — that snap with a special excitement that comes from the perfect convergence of character, situation, acting, camera placement and cutting…

…The technical side of the film is occasionally so dreadful — with mismatched movements and lighting, clumsily speeded-up motion for no reason except to get a bit of exposition over with more quickly, poor dubbing, peripatetic matte shots, too-long dissolves, unnecessary crescendos in the score — that Robin Wood should have a more difficult time than usual defending these inept process shots as Hitchcock’s jaundiced comment on the Industrial Age’s planned obsolescence…

…Not only does Topaz have too much operatic small talk, and not only does the opening aria — the smuggling of a Russian defector out of Denmark — seem needlessly distended, but the lead singer is about as capable in his role as Mrs. Miller would be in La Traviata. Frederick Stafford, an actor of indeterminate nationality and few movie credits (he starred in Andre Hunebelle’s OSS 117 — Mission for a Killer, released here in 1966), has what purports to be the leading role, that of a French intelligence agent stationed in Washington, with a branch office in Cuba. Stafford is terrible. He’s posey, wooden, smug, pausing over a brandy snifter like an early-talkie actor reading his lines into a hidden mike. In fact, Stafford’s badness is so consistent, almost stylized, that he is suggestive not of the individual bad actors one encounters in most movies, but of whole genres of bad actors… A good actor makes you feel he’s been inhabiting a character for years, and each nuance evokes a lifetime of experiences, choices and emotions. Stafford, and Dany Robin as his frigid wife, convey to the viewer nothing but the nervousness they feel in characters they don’t understand…

…Though Topaz is a leading man’s nightmare, it’s also a character actor’s dream. John Vernon, a powerful young Canadian actor (Point Blank, Justine, Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here), is outstanding as a manic Castro aide. His black beard and marble-blue eyes first attract our attention, but Vernon keeps himself there by adding, to the Raf Vallone — “I am ze bool” hysteria of the role as written, an unusual amalgam of lust and tenderness for his mistress (who is really Stafford’s beloved, and a devoted anti-Communist), the heroic, warm, womanly Karin Dor. The scenes between Vernon and Dor are so superior to those with Stafford and Robin that you wonder how Hitchcock could have directed one feuding couple with extraordinary passion and tactile vividness, while letting a similar scene go memorably flat. The difference probably has as much to do with that felicitous congeries of situation and inspiration, of action and passion, of actor and character, as it does with any directorial epiphanies. Whatever the cause, these sequences in Dor’s villa are complex, human, and beautiful. They lead from Stafford’s idyll with his real love (who manages to spark this mannequin to real life), through Vernon’s discovery that Dor has betrayed him and her government — and it is a measure of Vernon’s and Hitchcock’s achievement that we can share the Castroite’s outrage and nearly tragic, cuckolded disillusionment — to her murder, photographed from above, her velvety violet dress filling the screen as she falls to the floor in a moving metaphor for the grace that informed her way of life and gives her final moral supremacy in their personal and political battle to the death. Throughout this whole middle section of the film, stereotypes become human beings, and Topaz comes vibrantly alive.

The final third of the film, in which Stafford discovers two Russian spies working in the French government, lacks the power and passion of the preceding encounter. Vernon and Dor are physical actors; Michel Piccoli and Philippe Noiret, who play the spies, are more intellectual, Piccoli in his suave assurance, Noiret in his Lorrean paranoia. The “confrontation” is in fact so oblique that it never really takes place. There is a luncheon for six, of whom two are spies. Hitchcock works over our suspicions through the use of supercilious glances and portentous camera angles, but the villains (the two charmers, of course) aren’t revealed until later, and Stafford never gets to tell them off. The movie just runs out, like a tube of toothpaste.

Part of Hitchcock’s problem is Leon Uris’s unwieldy book, based on a true spy story that is more coherent than the novel and more shocking than the movie… Topaz, a 400-page novel cluttered with insignificant (presumably documentary) detail and dramatically irrelevant characters, offered a challenge not only of condensation but of elaboration; and here, Hitchcock and scenarist Samuel Taylor (Sabrina, The Monte Carlo Story, Vertigo, Three on a Couch) have performed admirably. Situations and characters have been first simplified and then enriched. The Soviet defector (Per-Axel Arosenius) is thus allowed to suggest that the difference between himself and his interrogators is that he is a severe, aristocratic Russian and they are open-faced middle-class Americans. Roscoe Lee Browne is given a few marvelous, largely wordless scenes that strip his character of Uris’s idiosyncrasies the better to let Browne create him anew with smiles and gestures. And Michel Piccoli is allowed to be himself: concerned, decadent, so graceful that he obliterates questions of morality…

…Beneath the mythical Hitchcock who is the author of everything grand in his oeuvre is a partly creative, mostly collaborate craftsman who must rely on the crucial contributions of his co-workers. Topaz, inept and ineffable, poorly acted and well-acted, shoddily shot and exquisitely shot, mediocre and transcendent, should be kept in mind before we send “Hitchcock” to the Pantheon or to critical perdition.” -Richard Corliss (Film Quarterly, Spring 1970)

Topaz is one of this reviewer’s least favorite of Alfred Hitchcock’s American films, but it is a film that seems to improve with each viewing. There are sequences that are undeniably brilliant. It would be a mistake to disregard the film entirely. However, I maintain that it would have been preferable to have Kaleidoscope take this film’s place in Hitchcock’s filmography.

The Presentation:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

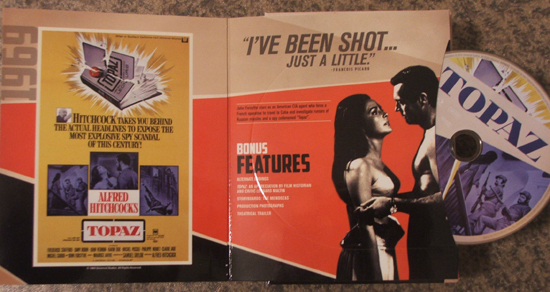

This disc is available as part of The Masterpiece Collection boxed set and as an individual disc.

The Masterpiece Collection is given a tasteful book-style presentation with a page for each film that includes a folder for each disc. Some might prefer that each disc come in its own standard Blu-ray case. These folder style compartments do not always protect the discs and very often cause scratches. There have even been reports of glue adhering to the actual disc, and rendering them unplayable.

The individual release presents the disc in a standard Blu-ray case with film related artwork.

The menu on the disc contains footage from the film accompanied by music in the same style as other Universal Blu-rays.

[Note: The extended 2 hour and 23 minute version of the film is featured here with the “airport ending.”]

Picture Quality:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

Universal’s VC-1 transfer exhibits excellent color resolution and impressive clarity. The sharp detail showcase the various textures accurately, and the grain structure remains consistent throughout the length of the film. Of course, the transfer does have a few flaws that keep it from being one of the better transfers in Universal’s Hitchcock catalog. There is a fair amount of source noise at certain points throughout the picture, and there are a few instances when the color fluctuates. Luckily, the skin tones are almost always consistent and natural looking. As is usual with most of Universal’s color films, there is a fair amount of digital tampering performed on the image. There may be a few minor image halos at certain points in the film. Overall, the transfer is satisfactory.

Sound Quality:

4 of 5 MacGuffins

The two channel mono soundtrack is quite clean, and showcases clear dialogue without any distracting noise or anomalies to distract from one’s enjoyment. The film’s music and sound effects are also well rendered here. There is very little room for complaint here.

Special Features:

3.5 of 5 MacGuffins

Topaz: An Appreciation – (29 minutes)

Laurent Bouzereau again directs this “appreciation” of Topaz, but an objective “making of” documentary would have been preferable. While Leonard Maltin attempts to walk the viewer through a few of the film’s production problems, there isn’t enough information here to put it among Bouzereau’s other documentaries for Universal’s Hitchcock catalog (most of which are excellent). It is nice that an effort was made, even if it doesn’t completely satisfy.

It manages to be just useful enough to maintain our interest, but it is disappointing to not have a more comprehensive look at the film’s creation. Why do we not include any information about Alfred Hitchcock’s preferred Kaleidoscope project? Where are the interviews with the actors and crew? Were they not willing to participate? John Forsythe appeared in The Trouble with Harry Isn’t Over. Why not question him about this film? These questions will have to go unanswered (just like our questions about Topaz).

Alternate Endings – (6 minutes)

All three of the film’s endings are included here (“The Duel,” “The Suicide,” and “The Airport”) “The Duel” isn’t complete, and seems to be in poor condition. This is probably because it was never a part of any official release due to the negative comments at preview screenings. The other two endings were both released in various markets, and appear to be in fine condition. It is interesting to compare these three endings.

Theatrical Trailer – (3 minutes)

This theatrical trailer is an interesting artifact. It features Alfred Hitchcock, but lacks the level of wit that one sees in some of his other trailers. It is certainly good to see it included here.

Storyboards: The Mendozas

“The Mendozas” sequence storyboards are shown with video footage of the film so that fans can make comparisons. This should interest fans of storyboarding.

Production Photographs

This is a slideshow of movie posters, vintage ads, and production photos. It is nice to see that this carried over from the earlier DVD editions.

Final Words:

Topaz isn’t one of Alfred Hitchcock’s better American films, but it is has moments of brilliance. Since the film seems to improve substantially with each viewing, fans will probably want to add it to their collection. Luckily, Universal’s Blu-ray transfer is a decent upgrade to the previous DVD editions of the film.

Review by: Devon Powell

Reblogged this on pundit from another planet.

Devon, what a thorough, interesting review. I enjoyed the section regarding studio suffocation and freedom. I think about him achieving this grand reputation and the need to protect that by creating art. Then all the players want to interfere. There’s something to be said about pre-star freedom before the money bags try to control you. Nice post.

EXCELLENT REVIEW AS USUAL!!! I agree with your personal assessment/opinion on Hitchcock’s TOPAZ to a tee! 🙂

So thorough, and really fascinating.

Thanks for the kind words. 🙂

Reblogged this on Travalanche and commented:

A terrific piece that does much to explain Hitchcock’s otherwise inexplicable “Topaz”

If you enjoyed this article, you might also find the article on “Torn Curtain” interesting.

Great review, as always! I’ve always suspected that Hitchcock really enjoyed shooting the Harlem sequence with Roscoe Lee Brown, because that section has a spark that is lacking in the rest of the film.