Distributor: Universal Studios

Release Date: May 10, 2022

Region —

4K UHD: Region Free

Blu-ray: Region A

Length: 01:47:49

Video —

4K UHD: 2160P (HEVC, H.265 – HDR10)

Blu-ray: 1080P (VC-1)

Main Audio: 2.0 English DTS-HD Master Audio (48 kHz, 1775 kbps, 24-bit)

Alternate Audio —

4K UHD: 2.0 French DTS Audio

Blu-ray:

2.0 French DTS Audio

2.0 Italian DTS Audio

2.0 German DTS Audio

2.0 DTS Japanese Audio

Subtitles —

4K UHD: English (SDH), French, Spanish, Japanese, German, Italian, Dutch, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish

Blu-ray: English SDH, Spanish

Ratio: 1.37:1

Bitrate —

4K UHD: 69.02 Mbps

Blu-ray: 31.51 Mbps

Notes: These are the same discs included in the “Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection: Volume Two” boxed set. The package also includes a digital copy of the film.

“Shadow of a Doubt was a most satisfying picture for me — one of my favorite films because for once there was time to get characters into it. It was the blending of character and thriller at the same time. That’s very hard to do.” —Alfred Hitchcock (The Cinema of Alfred Hitchcock / Who the Devil Made It, 1963 / 1997)

Alfred Hitchcock’s Favorite Film: The Making of Shadow of a Doubt

Most of the articles and essays that discuss Shadow of a Doubt are quick to mention that it is the director’s favorite of the films that he directed, but the truth is that this is probably something of an oversimplification. It is true that when journalists asked him to name his favorite of the films that he made, he would usually respond by discussing this film. This is what happened during a 1956 interview with Charles Bitsch and François Truffaut for Cahiers du Cinéma.

“I was fortunate to find in Thornton Wilder an ideal collaborator, thanks to whom the characters in this film are successfully conceived. Suspense, psychology, character traits, setting, everything pleases me in Shadow of a Doubt. It’s an exceptionally solid film, very solid.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Encounter with Alfred Hitchcock: Interview with Charles Bitsch and François Truffaut, Cahiers du Cinéma, August-September 1956)

He would expand on this answer during the John Player Lecture with Alfred Hitchcock (which was moderated by Bryan Forbes) when he was asked the same question, but he added another film to his practiced response.

“Probably two films. The first one is a picture called Shadow of a Doubt, which I wrote with Thornton Wilder, and this was one of those rare occasions when suspense and melodrama combined well with character. And it was shot in the original town and at that time they were shooting an awful lot on the back lot. So it had a freshness. The other film is Rear Window, because to me that’s probably the most cinematic film one has made. And most people don’t really recognize this because the man is in one room and in one position. But nevertheless, it’s the montage and the cutting of what he sees and its effect on him that creates the whole atmosphere and drama of the film. In other words, the visual is transferred to emotional ideas, and that film lends itself to that.” —Alfred Hitchcock (The John Player Lecture, March 27, 1967)

However, Hitchcock backtracked on this stance a few years earlier during his legendary interview with François Truffaut.

“I wouldn’t say that Shadow of a Doubt is my favorite picture; if I’ve given that impression, it’s probably because I feel that here is something that our friends, the plausibles and logicians, cannot complain about… The psychologists as well! In a sense, it reveals a weakness. On the one hand, I claim to dismiss the plausibles, and on the other I’m worried about them. After all, I’m only human! But that impression is also due to my very pleasant memories of working on it with Thornton Wilder.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Le Cinéma selon Hitchcock, 1966)

Of course, this may have been the director’s response to Truffaut’s comment that although the film is the one that he favors, “it gives a rather distorted idea of the Hitchcock touch.” Even so, one feels that there is probably a lot of truth to Hitchcock’s response. It would have been in character for him to provide an answer that wouldn’t be negatively scrutinized by the critics, and he did have fond memories of the film’s production.

Universal had worked out a deal with David O. Selznick to employ the director a second time for the substantial sum of $150,000 for eighteen weeks of work. Of course, Hitchcock would only receive $50,000 of this sum with the bulk of the money going to Selznick. In addition, the director was to receive “above the credits” billing for the film (which was a first for the director). The only problem was that Hitchcock wasn’t certain what his next film should be after completing Saboteur.

“On April 13 Margaret McDonell, one of Selznick’s story editors, invited Hitchcock to lunch and suggested several ideas. Patrick Hamilton’s play ‘Angel Street’ had been turned into a film script called Gaslight, and she thought it would be just right for him. But he turned down the costume melodrama in spite of its thriller aspects, insisting that he had learned his lesson about period pieces from Jamaica Inn. The only other idea that interested him was something she had remembered called ‘The Ventriloquist.’ For several days after this lunch, Hitchcock worked alone on a treatment of this curious idea: A ventriloquist commits bigamy, murders his first wife and, haunted by his crime, confuses reality with paranoiac delusion. As his second wife comes to warn him that the police are in pursuit, he mistakes her for his first wife, and in his fear falls over a cliff to his death. ‘Hitchcock really likes this!’ Mrs. McDonell reported to Selznick next day. But Selznick thought it was entirely too bizarre, and while Hitchcock tried to write up a treatment, he was told the idea had been rejected… When Selznick rejected the idea, Hitchcock at once left town for several days — officially to supervise some technical problems with the musical scoring of Saboteur in New York. He also went to Washington, to assure the capital’s press corps that the film would be perfect for a War Bond rally. When he returned to Hollywood, Margaret McDonell suggested doing a film of John Buchan’s novel ‘Greenmantle,’ with Ingrid Bergman, Cary Grant, and Herbert Marshall, or Buchan’s ‘No Other Tiger,’ a story of jewel theft. (‘Hitch enthused particularly,’ Mrs. McDonell reported, ‘about the climax where the beautiful dancer is found hanging from the chandelier.’)” —Donald Spoto (The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock, March 01, 1983)

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), he was unable to secure the rights to the property and decided to find another story to fuel his creative urges.

“Though stymied from remaking The Lodger, he thought about crafting a Hitchcock original about a more modern serial killer. Steeped in crime lore since boyhood, Hitchcock had well-honed reflexes when fashioning such a film. These stories were so deeply rooted within him, so instinctual, that he gave them a name: ‘run-for-cover’ films. ‘Whenever you feel yourself entering an area of doubt or vagueness,’ he once said, ‘whether it be in respect to the writer, the subject matter, or whatever it is, you’ve got to run for cover. When you feel you’re at a loss, you must go for the tried and true.’” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

It turns out that Margaret McDonell had been overlooking a story that was almost made to order for the director. As it happened, she was married to a writer named Gordon McDonell.

“Let’s go back a little into the history of the picture. A woman called Margaret McDonell, who was head of Selznick’s story department, had a husband who was a novelist. One day she told me her husband had an idea for a story, but he hadn’t written it down yet. So, we went to lunch at the Brown Derby, and they told me the story, which we elaborated together as we were eating. Then I told him to go home and type it up. In this way we got the skeleton of the story into a nine-page draft [actually six pages] that was sent to Thornton Wilder.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Le Cinéma selon Hitchcock, 1966)

Gordon McDonell later wrote about how he came upon the idea for the story in a letter to Hitchcock.

“…We were staying down in Hanford when our car had broken down in the High Sierra and we had gone down to get it repaired. It was in 1938, just while I was beginning to mull over the vague stirrings of my present book that I am still working on. There we were, stuck in that little place and it was so hot and dry and dusty and small town. And then I thought of it and later when we were up in the mountains again, I told Margaret’ and she said I must write it as a book. I said I never would, because I wanted to write what I am writing and nothing else. Ever since then ’Uncle Charlie’ has been in our family and we have often spoken of him as though he existed.

Then, so long afterwards, [Margaret] said to me one day she was searching and searching for a story for you. By then we had forgotten about Uncle Charlie and then that evening he came into my head. I did not know why he did just then: I wasn’t I wasn’t consciously thinking of a story for you because I never think of anything except my book. Suddenly I connected up you and Uncle Charlie and I jumped up and said: ‘Margaret, what about Uncle Charlie for Hitch.’ And she said, ‘Why, of course – what fools we were not to think of him sooner.’ . . . You know the rest.” —Gordon McDonell (Letter to Hitchcock, January 10, 1943)

The treatment that Hitchcock mentioned to Truffaut appears in “Dan Auiler’s “Hitchcock’s Notebooks: An Authorized and Illustrated Look Inside the Creative Mind of Alfred Hitchcock,” and there are quite a few notable differences from the film:

“The story is set in the little town of Hanford in the San Joaquin Valley, a typical American small town almost lost between the desert and mountains. In Hanford lives an unimportant little family of four — father, mother, daughter, and son. They are little people, leading unimportant little lives. The father is a small and rather timid employee in the local bank. The son, about 19, has a job but not a very good one, and there are very few prospects for him in the small town. The daughter is a girl of about 18 with great potentialities of charm. Given the right chances one feels she could develop her real natural intelligence and make something out of her quite considerable beauty. But in Hanford there is nothing for her. She takes on much of the burden of housekeeping in the little household, trying all the time to spare her semi-invalid mother the work which seriously affects her health. She has become engaged, half against her own better sense, to the town’s ne’er-do-well. He is always half in trouble, footloose, discontented, often railing in speech against the humdrum respectability of the smug little town.

As a result, whenever anything goes wrong in town, when a small local holdup finally attributed to tramps empties the cash register of the local drug store, town gossip at first ascribed the holdup to the ne’er-do-well. The instinct throughout town is to fasten blame on him whenever possible. The girl herself, is often swayed by public disapproval and yet she clings halfheartedly to their engagement just because her future is so empty.

The little family are always struggling to come up in the world socially. It is very important to them, and they count their small social successes very tenderly, for instance, the evening when the mother has to deputize as chairman of the local mooting of the Women’s Club, is a red latter day; it is almost THE BEGINNING OF BETTER THINGS. The struggle to ‘climb to reach the Joneses’ is just as hard a one in the little town of Hanford as it would be in London or New York and just as important to the climbers, but when the story opens, and the hot weather has descended once again to burn up the smug little streets and fill the air with biting dessert dust. It looks like just another year when nothing will ever happen. Life passes Hanford by; there are no high spots, there are never even any crimes.

A letter addressed to the mother arrives which is the whole keynote of life for the little family. It comes from Uncle Charlie, the gay, handsome, successful, debonair brother whom the mother has not seen for ton years. To the girl and her brother, Uncle Charlie in anecdotes has become quite a legendary figure, the hero of so many exploits of the mother’s girlhood. Always it has been their hope that one day they would see and know Uncle Charlie for themselves, and now a letter comes from a fashionable New York hotel telling them that Uncle Charlie is on his way west and is coming to visit them. At once the summer becomes exciting and lively and the little house is alive with plans. The girl sees the flush of vitality again in her mother’s cheeks as her mother hurries from house to house to tell everybody proudly the news of Uncle Charlie’s visit. Little teas are arranged in advance, and a whirl of small-town gaiety is planned. The President of the Women’s Club approaches the mother hoping that Uncle Charlie will favor then with a talk on some of his travels.

Then Uncle Charlie arrives, and he is all and more than any of them expected. Distinguished, entirely charming, very polished, and a man of the world, he captivates them all, and the household takes on an entirely new lease or life. Uncle Charlie has the gift of unique sympathy and is able to deal with every member of the family in just the way needed to galvanize them into making better use of themselves. Under his influence, the father loses much of his feeling of inferiority and gets a better position in the bank, the young son is spurred by Uncle Charlie’s vigorous encouragement to go out and look for a job in a bigger city with a future to it. The mother becomes an entirely different person. She once again takes an interest in her appearance and her faded prettiness blooms again. On that account alone Uncle Charlie wins the gratitude of the girl. To her it is the greatest gift he could have brought that he has given so much of health back to her fading mother. Between Uncle Charlie and the girl there springs up a very close relationship.

He is wonderful to her in a way that no man has ever been before, bringing to her a breath of that wide outside world she has longed to visit. Evidently well supplied with money Uncle Charlie showers her with pretty things, brushing away her protests by saying that this is the least an uncle can do for his pretty niece. He is unalterably set against her fiancé. The two men start off on the wrong foot and are antagonistic from the start. The worst side of the fiancé always seems to be brought out in ugly contrast to Uncle Charlie’s polished manner so that many an evening ends in the young man making a surly fool of himself. Uncle Charlie is quite outspoken in urging the girl to have done with this misalliance, saying that she is throwing herself away on such an oaf and that he himself will take her along with him and show her some of the world.

Then gradually, although her head is almost turned by the attentions of this good-looking man of the world, little things begin to bother the girl about him. She begins to wonder about his life, about his past, and one day while tidying up his room in his absence, she is impelled by curiosity to go through his trunk. In it she finds some clippings dealing with two or three isolated murder cases. A terrible instinct hits her. Then she is furious with herself for having such thoughts about the man who has become their benefactor. She tries not to think about it again, but again and again she returns to search his room and each time she finds something that makes her suspicion grow. Finally tucked away in a corner of his trunk, she finds a pretty dainty chiffon scarf. A memory strikes her, and she ruffles through the clippings to find the description of the most recent murder, that of a young girl which took place a couple of months earlier. The murder weapon bad been a flowered chiffon scarf.

She slams the trunk shut and turns to run, but as she rushes out of the door Uncle Charlie comes in. Her eyes are unguarded and as she faces him for that brief instant, he sees in her eyes that she knows he is the murderer.

She is utterly torn between whether to hand him over to the police or whether to let things slide. If she hands him over to the police, the whole life of the little family, above all her mother’s life will be ruined for good and all. In a small town like Hanford such a scandal could never be lived down. The town would have been made a fool of, having opened its hospitable door to a murderer. The revelation of the truth might even kill her mother. Feeling unable to bear this choice alone she tells her fiancé about it and he turns out in this, her greatest crisis, to be a strong and solid prop. He does not try to force her to go to the police, understanding that she has to work that out alone, but he does stand by her in a way which welds them very closely.

The girl’s one object while making her decision is to avoid Uncle Charlie, and Uncle Charlie’s one object is to get her alone. Terrified, she realizes that his only means of silencing her is to kill her. Several times he almost succeeds in getting her alone, once when he sends the whole family out to a movie and returns to the house, but she escapes out of her bedroom window, although she knows that this cannot go on for long.

Then Uncle Charlie arranges a large picnic in the foothills. They all drive out in oars across the desert floor and park below the towering, crumbling sandstone cliffs which are the beginning of the mountains. It is the gayest of picnics, but to the girl it is a haunted evening for she has decided that even if it kills her mother, she cannot let the murderer go free. Then by clever planning, when they start home Uncle Charlie manages so that the whole of the cavalcade of cars leave and start off into the sunset across the desert floor, no one realizing that the girl has been left behind a little way up one of the cliffs they have been climbing. When the last car has driven off into the dusk and the evening silence has settled down over the desert, he begins to climb to meet her. Coming down she sees him approaching and knows that this is the end, that soon she will be found entirely crushed and broken at the foot of the crumbling rocks, the victim of a tragic “accident.”. She turns and, panic-stricken, struggles wildly up the crumbling hillside, but the man gains on her. She reaches the crest and turns as he comes toward her. They are on the edge of the cliff. Uncle Charlie’s hands go out, but the girl jumps aside. From a little below comes the sound of a sudden shout. The fiancé has realized that the girl has been left behind and is racing up the hillside. Uncle Charlie makes a lunge, but the shout startles him, and he misses his hold. Just as the piece of cliff on which he is standing breaks away and falls carrying Uncle Charlie down with the mass of rocks and loose earth to crash to the desert floor below.

The broken body of the well-liked Uncle Charlie is brought reverently and tragically home to Hanford by a score of willing volunteers who rush out to the scone of the ‘accident.’ Condolences and glorious floral tributes pore into the grief-stricken little household and the whole of Hanford turns out to do honor to the guest in a funeral the like of which has seldom been seen in the small town. As they drive along in the funeral procession, the girl and her fiancé are the only people who knew what Uncle Charlie really was and what his death has spared the mother.” —Gordon McDonell (Treatment, May 05, 1942)

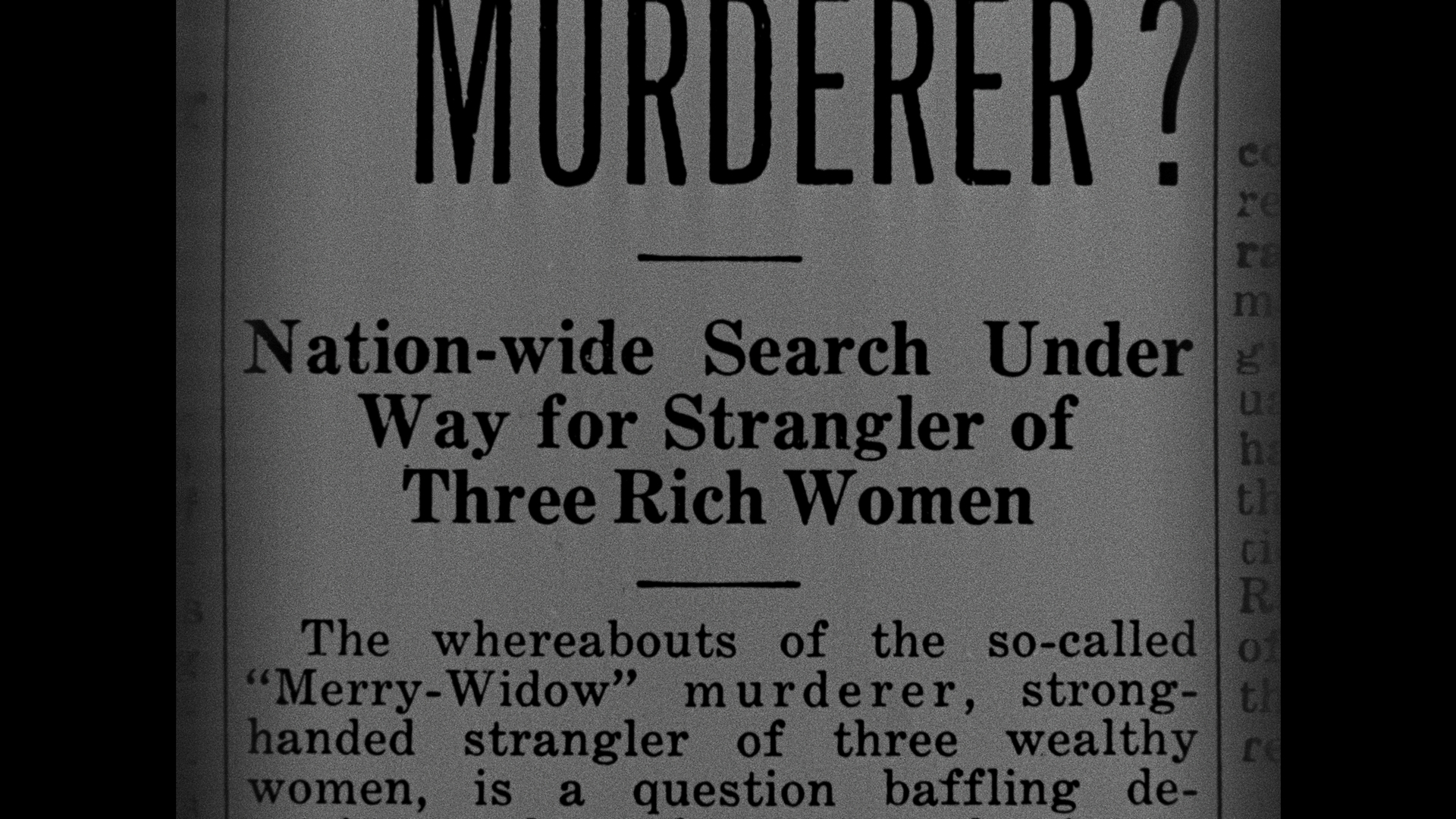

This skeleton of a story triggered something within Hitchcock. It reminded him of a number of famous true crime cases. The first was a famous series of murders that occurred in the 1920s. Earle Leonard Nelson would travel the country while strangling women to (most of whom were middle aged). We won’t get into the things that he would do after their death, but one can see that Hitchcock used him as a jumping off point for his work on the eventual screenplay. Another source of inspiration was Henri Landru (who was later used as a source of inspiration for Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux).

Hitchcock was on board but felt that a more detailed treatment would be helpful and asked McDonnel if he would be interested in working with him to flesh out some of the details. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), the writer was working on a novel and didn’t want to interrupt his progress.

Working with Thornton Wilder

“It was up to Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock to brainstorm the initial ‘Notes on Possible Development of Uncle Charlie Story for Screen Play,’ which they did on May 11, 1942, outlining the director’s formative vision for the film. Although McDonell had posited ‘a typical small American town’ with ‘little people, leading unimportant little lives,’ Hitchcock was worried about that word ‘‘typical,’’ wary that it suggested a cast of stock figures. So, he and his wife modified the town into a place invaded by modern evils (‘movies, radio, juke boxes, etc.; in other words, as it were, life in a small town lit by neon signs’), with a sympathetic, individualized family whose members would lend themselves to plenty of comedy — especially ‘from the characters ‘‘not in the know.’’’

Working without Joan Harrison for the first time in nearly a decade, and needing to flesh out McDonell’s brief story, Hitchcock wanted a writer with more experience than Peter Viertel [who had worked with the director on Saboteur]. Just as he sprinkled his films with American landmarks, Hitchcock liked to add a dash of literary prominence to their credits — and now he went looking for ‘the best available example of a writer of Americana,’ as he later put it. Miriam Howell, producer Sam Goldwyn’s literary agent in New York, made a suggestion: Thornton Wilder… When Hitchcock wired him, Wilder had just completed ‘The Skin of Our Teeth,’ destined to become another stage classic.

Wilder had one free month before he was due to join army intelligence [the Psychological Warfare Department]. Though he was intrigued by the prospect of writing a Hitchcock film, he complained to his friend, the famous journalist Alexander Woollcott, that the story idea sounded ‘corny.’ Yet Wilder also wanted to make some quick money to tide over his mother and sister while he was in the army. His agent requested fifteen thousand dollars for the script, payable in increments for five weeks of work. It was a princely sum, but Wilder was a princely name, and Jack Skirball immediately authorized the contract. On May 18 Wilder boarded a train; three days later he was meeting with Hitchcock, staying at Hollywood’s Villa Carlotta and commuting to Universal.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Hitchcock and Wilder both got along wonderfully and found the process rewarding.

“In England I’d always had the collaboration of top stars and the finest writers, but in America things were quite different. I was turned down by many stars and by writers who looked down their noses at the genre I work in. That’s why it was so gratifying for me to find out that one of America’s most eminent playwrights was willing to work with me and, indeed, that he took the whole thing quite seriously… He came right here, to this studio we are now in, to work on it. We worked together in the morning, and he would work on his own in the afternoon, writing by hand in a school notebook. He never worked consecutively but jumped about from one scene to another according to his fancy. I might add that the reason I wanted Wilder is that he had written a wonderful play called ‘Our Town.’” —Alfred Hitchcock (Le Cinéma selon Hitchcock, 1966)

The duo was soon making important alterations to Gordon McDonell’s original treatment, and these changes extended to the Newton family. The teenage brother in the treatment became a younger brother and sister while the mother was no longer the pathetic invalid found in the treatment. Meanwhile, young Charlie’s moody boyfriend was replaced with a police detective that eventually becomes her love interest. A brand-new opening was also invented.

“In McDonell’s sketchy version of the story Uncle Charlie isn’t introduced until he materializes in the small California town. Hitchcock wanted some kind of prelude that would show Uncle Charlie before his arrival, already frantic and on the run. Most comfortable with East Coast settings, Wilder proposed an opening sequence showing Uncle Charlie holed up in a New Jersey boarding-house. The police are shadowing him, and he is pondering his next move. ‘There’s this short story by [Ernest] Hemingway,’ suggested Wilder, ‘where a man is lying in bed in the dark, waiting to be killed. That would make a good opening.’ Hitchcock was taken aback. The great Wilder was a practical craftsman, it turned out — just like him — not above a little pilfering to get the job done. The New Jersey opening would give the film a more national scope. And that is just how Shadow of a Doubt would begin, with a tacit nod to Hemingway’s well-known story ‘The Killers.’” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Hitchcock’s enthusiasm was contagious and soon rubbed off on Wilder, and he was surprised to find that the collaboration was so creatively fulfilling.

“Work, work, work… But it’s really good. For hours Hitchcock and I, with glowing eyes and excited laughter, plot out how the information — the dreadful information — is gradually revealed to the audience and the characters. And I will say I’ve written some scenes. And that old Wilder poignance about family life [is] going on behind it. There’s no satisfaction like giving satisfaction to your employer.” —Thornton Wilder (Letter as quoted in “Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light,” May 26, 1942)

Their enthusiasm resulted in quite a lot of progress on the script.

“My god, I’m not only getting money, but I’m getting pleasure… Seventy pages of the script went to the typist’s today — 20 more tomorrow. It only has to be 130. Today and yesterday Hitch and I devised the ending. Honest, I think it’ll be an awfully absorbing picture.” —Thornton Wilder (Letter as quoted in “Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light,” June 1942)

Even though they were making amazing headway, they weren’t quite finished by the fifth and final week of Wilder’s engagement in Hollywood. When Wilder headed east by train for army duty on June 24, Hitchcock and Jack H. Skirball traveled with him so that they could continue their work. The final pages of the screenplay were completed somewhere between California and New York, but the script would still need a good polish.

“I felt there was still something lacking in our screenplay, and I wanted someone who could inject some comedy highlights that would counterpoint the drama. Thornton Wilder had recommended an MGM writer, Robert Audrey, but he struck me as being more inclined toward serious drama, so Sally Benson was brought in.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Le Cinéma selon Hitchcock, 1966)

Polishing the Script

Benson was enjoying an enormous amount of success at the time as “Junior Miss” — both her short story collection and the Broadway play that was adapted from it — were embraced by an enthusiastic public in 1941. She was a highly regarded writer of short fiction.

“Besides adding comedy and modern tinges to Shadow of a Doubt, Hitchcock wanted her to add freshness to his family portrait. Benson became the fourth writer from ‘The New Yorker’ (where she also reviewed mysteries and occasional films) to be recruited by Hitchcock. At first Benson worked from New York, her pages integrated into the continuity by Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock. Then, just before the late summer start of production, she came to California and spent two weeks writing on the set. ‘The rewrite greatly improved Wilder’s very rough draft,’ according to film scholar Bill Krohn.

Counting Gordon McDonell and both Hitchcocks, five writers worked on Shadow of a Doubt. Make that six: up on location, actress Patricia Collinge, who played young Charlie’s mother, contributed to her own characterization — removing all traces of the ‘rather silly woman’ of the shooting script, according to Krohn. She also touched up the romantic interlude in the garage between young Charlie and the police detective, which takes place after Uncle Charlie seems to have been cleared.

In the end, only four writers were credited on the screen: McDonell, Benson, Wilder, and Alma Reville. Being rewritten by Sally Benson — or a supporting actress, for that matter — didn’t alter Wilder’s favorable view of the experience; nor did it detract from Hitchcock’s opinion of Wilder. Indeed, the director gave Wilder an unusual citation, which ran in the credits just before Hitchcock’s own name: ‘We wish to acknowledge the contribution of Mr. Thornton Wilder to the preparation of this production.’ … ‘It was an emotional gesture,’ Hitchcock said of the unusual credit. ‘I was touched by his qualities.’” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Of course, scholars have theorized that Patricia Collinge’s Emma Newton might be a tribute to Alfred Hitchcock’s own mother (who was also named Emma). The director himself admitted that this could have been the case.

“It has been said that I based the character of the mother in Shadow of a Doubt on my own mother. I can tell you that I did not deliberately do so, nor did I deliberately avoid doing so… In this particular case, however, I have to admit that it was a time when I was thinking about my mother, who was in London. There was the constant danger from the war, as well as her own failing health. She was in my thoughts at the time. I suppose that if we think about a character who is a mother, it is natural to start with one’s own. The character of the mother in Shadow of a Doubt, you might say, is a figment of my memory.” —Alfred Hitchcock (as quoted in “It’s Only a Movie: A Personal Biography of Alfred Hitchcock,” 2005)

Donald Spoto would go into more detail about Emma Hitchcock’s failing health and how it affected the director in his famous biography of Hitchcock.

“Just as Hitchcock began to work on the [later drafts of the] script, something happened that entirely altered its content, theme, and purpose: he began to receive frequent and worried letters and cables from England, informing him that his mother had suddenly developed a series of complicated conditions that put her in very poor health. There were kidney problems and intestinal obstructions. William Hitchcock let his brother know that he was alarmed — especially because their mother refused to enter a hospital and would take only what care she could get at home, in the cottage in Shamley Green. Hitchcock, of course, was on a strictly controlled schedule under Skirball and Universal… In addition, it was not easy to book air travel to England in the summer of 1942 — and a boat trip, even for the best of reasons, would simply require too much time. And so, he remained in California, a decision no one faulted him for but that cost him considerable personal anguish… [Hitchcock’s mother] developed an intestinal abscess, slipped in and out of coma, and was receiving daily visits from a physician. Her youngest son told no outsiders of this increasingly bad news but his fervent involvement in polishing and re-polishing — and personalizing — the script continued at unprecedented pitch.” —Donald Spoto (The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock, March 01, 1983)

Hitchcock’s worries about his mother’s health were a cloud that hovered over the otherwise sunny production of Shadow of a Doubt, and on September 26, 1942, during the final weeks of principal photography, she passed away at age seventy-nine from an intestinal perforation, acute pyelonephritis, and an abdominal fistula with William Hitchcock at her bedside. William Hitchcock would pass away only five months later from what might have been a self-administered dose of paraldehyde but going into all of that would be an unnecessary digression. However, these events are certainly worth mentioning as they had an enormous impact on the director’s state of mind at the time.

“Hitchcock’s reactions to the two deaths are not recorded, but it is known that he began to lose a great deal of weight in the following months. Mortality beckoned. By the end of 1943 he had shed one hundred pounds, which was a cause of concern to David Selznick. He wrote that ‘I am sincerely and seriously worried about Hitch’s fabulous loss of weight. I do hope he has a physician, as otherwise we are liable to get a shock one morning about a heart attack or something of the sort.’” —Peter Ackroyd (Alfred Hitchcock: A Brief Life, May 04, 2015)

In any case, the final script was dated August 10th, which was a little over a week after Hitchcock started production on the film. Things were moving very quickly. The director had already scouted locations with Thornton Wilder and Jack Skirball after deciding that the film’s story should be set in Santa Rosa, California (instead of the San Joaquin Valley as Gordon McDonell had suggested). They took a thorough tour of the city that took them to such locations as their train station, telegraph office, local library, the American Trust Company Bank, and various houses to serve as the Newton house (the film’s primary location).

“Wilder and I went to great pains to be realistic about the town, the people, and the decor. We chose a town, and we went there to search for the right house. We found one, but Wilder felt that it was too big for a bank clerk. Upon investigation it turned out that the man who lived there was in the same financial bracket as our character, so Wilder agreed to use it. But when we came back, two weeks prior to the shooting, the owner was so pleased that his house was going to be in a picture that he had had it completely repainted. So, we had to go in and get his permission to paint it dirty again. And when we were through, naturally, we had it done all over again with bright, new colors.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Le Cinéma selon Hitchcock, 1966)

It might also be worth mention that Santa Rosa was in the same general area of Hitchcock’s northern California home.

“Working at Universal had already afforded Hitchcock a new measure of freedom, and now the war created an unexpected advantage: the U.S. government had placed a ceiling of five thousand dollars on new set-building costs. Making a virtue of necessity, Hitchcock convinced his amiable producer that they could shoot much of Shadow of a Doubt on location in Santa Rosa, saving on sets while displaying a picturesque town straight out of Norman Rockwell. Hitchcock was excited, looking forward to ‘reverting to the ‘‘location shooting’’ of early movie days,’ according to Universal publicity. ‘Beautiful countryside,’ he told Hume Cronyn later on. ‘Miles and miles of vineyards. After the day’s work we can romp among the vines, pluck bunches of grapes and squeeze the juice down our throats.’” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Production

The entire company was off to Santa Rosa by July 30, 1942. It hadn’t been three months since Hitchcock had devoured Gordon McDonell’s treatment. Husbands and wives traveled along with those working on the film, and this contributed to a warm familial environment on the set.

“‘There was very much a family feeling,’ recalled Wright. ‘When you are on location you are much closer to each other than when you are in the studio, coming from your own home to work. All of that lent itself to the film. A lot depends on things that go on behind the scenes.’

Behind the scenes, location work with a family in tow could also breed chaos. On location in Santa Rosa, Hitchcock was vexed by the weather, which played tricks with the light, and by curious crowds, who pursued the Hollywood folk everywhere. (Whenever possible, locals were hired for bit parts and extras.) Hitchcock had to change some day scenes into night; and as in the silent days in London, he sometimes had to work past midnight in order to close down and take control of the streets.

This was the first time the American press streamed to a Hitchcock set, lured by the novelty of the location angle and by interviews with an always quotable director. Universal may have been a lowly studio in some regards, but its publicity department was among the best. Reporters from ‘Life,’ ‘The New York Times,’ and Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco newspapers, and from the screen trade publications, as well as wire-service representatives, were all invited to watch. Publicity for Rebecca, orchestrated by Selznick International, had lionized the producer and director equally; now Universal focused its publicity on Hitchcock, and the clippings boosted his growing celebrity outside New York and California…” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

The press made a lot out of the war time production restrictions that Hitchcock turned to his advantage. One particularly informative article appeared in “Life” magazine, and it focused primarily on how wartime production restrictions only served to lend verisimilitude to the production.

“As a director of one of the first movies to be produced under the Government restriction placing a $5,000 ceiling on new materials used for sets, he has shown he has more than one trick up his sleeve. Accustomed to spending more than $100,000 on sets alone for one picture, Hitchcock made Shadow of a Doubt by reverting to the ‘location shooting’ of early movie days. Instead of elaborate sets he used the real thing. To shoot scenes supposed to take place in New Jersey, he traveled cross-country and shot them in New Jersey. Instead of building a studio version of a typical American city, his main setting, he searched for a ready-made one. Selecting Santa Rosa, Calif. (pop. 13,000), Hitchcock with his cast and crew took over the entire city for four weeks, converted it into a complete motion-picture studio. The result is an exciting and highly realistic film, whose new set cost, mainly for studio replicas, was well under the imposed limit.” —Dean Flower (Shadow of a Doubt: $5,000 Production, Life, January 25, 1943)

The article even included a set budget for the production:

Joseph Valentine (the film’s cinematographer) even wrote a lengthy article for “American Cinematographer” about the production that is full of juicy details about the challenges of photographing the film:

“During the past several years we’ve become accustomed to building whatever we wanted in the way of sets, whether it was a small bedroom interior or the exterior of an entire town. Production was much more convenient that way — especially for the sound man, at first, but almost equally so for the director and cinematographer, who found their phases of the work were more completely under control when working within the studio. So, with the exception of Westerns we had got out of the habit of sending more than a skeleton company on location. It was so much simpler to build even large exteriors on the stage, or to film them as process shots.

But today we can’t build those sets. With a war-time ceiling of 85,000 on new set construction for an entire picture the building of large sets like these is definitely out for duration. Yet we still need those sets; so, we must go outside the studio and shoot the real thing. In many ways I’m convinced this is likely to turn out to be an advantage. Technical problems all along the line are likely to be increased, of course, but in exchange we’ll get a note of realism in both background and camera treatment which is definitely in tune with what audiences want today.

Our Santa Rosa location was chosen because it seemed so typical of the average American small city, and offered, as well, the physical facilities the script demanded. There was a public square, around which much of the city’s life revolves. There was an indefinable blending of small town and city, and of old and new, which made the town a much more typical background of an average American town than anything that could have been deliberately designed. From the technical viewpoint most of our day exteriors were of a comparatively routine nature. The Santa Rosans were very cooperative, and most of our problems in these scenes were the ordinary ones of rigging scrims and placing reflectors or booster lights where they were needed.

In some of the scenes around the house we had selected to represent the home of our picture’s family, however, we had some problems in contrast. In building a set of that nature we are accustomed to placing trees and the like largely for decorative value. But here they had been planted to provide shade —and they certainly provided it! The troubles we had in controlling the balance between the brightly sunlit areas and the deeply shaded ones left me with an unending respect for what America’s amateurs manage to achieve with their Cine-Kodaks under similar circumstances, and without the professional’s opportunity of controlling contrast with scrims, reflectors and boosters!

The most spectacular part of our work was naturally the making of the night exterior sequences. We had with us two generator sets, ten 150-ampere arc spotlights, and the usual assortment of incandescent units — Seniors, Juniors, 18s, 24s, and broads — making a total of 3,000 ampere maximum electrical capacity. With this we lit up an expanse of four city blocks for our night-effect long shots!

Most of the credit for this must certainly go to the high sensitivity of the Super-XX negative I used throughout the production. In emergencies like this Super-XX lets a cameraman get the maximum effectiveness out of every light; in this instance, we successfully lit up an area which only a few years ago would have demanded four or five times as much illumination to produce an inferior result. Yet on more routine shots, outdoors or in the studio, the same film gives me a pleasingly normal gradational scale which no other film can equal.

Oddly enough, one of our less spectacular night scenes proved really the harder problem. This was a sequence played around the city’s public library. This building is a lovely Gothic structure, almost completely clothed in ivy. I think all of us were surprised at the way those dark green ivy leaves drank up the light. Actually, on our long shots of that single building we used every unit of lighting equipment we had with us—and we could very conveniently have used more if we had had them!

On some of our other scenes, though, the amazing speed of Super-XX opened up striking pictorial effects to us. There was one night scene, for instance, by the railway station, where with a bare minimum of front light to illuminate the players, a single 150-amp, arc spotlight placed nearly 200 feet from the camera cast a beam of three-quarter backlight which gave an excellent pictorial effect, and a most realistic one.

Lighting up windows on the scale we had to do it in our night-effect long shots was something we could hardly do by the usual studio method of putting a broad or a sky pan behind each window. Here again the speed of Super-XX proved invaluable. We went to Santa Rosa well supplied with Photoflood globes — we must have had about a thousand of them—to use for this purpose. Sometimes we used them in inexpensive “clamp-on” reflectors, but often enough we would simply screw a Photoflood into any convenient socket in the room which was to be lit. The results on the screen were precisely what we wanted, and by using the Photofloods we could avoid making an additional drain on our rather limited electrical supply, for the Photofloods could be used safely on any home or office lighting circuit.

On several occasions we made use of a little trick which is rather interesting. In setting up for several of the more intimate night scenes, we found that we could get a better composition and a more natural effect if there were two or three illuminated house windows showing here and there in the background, as from a house in the next block. Only, no house existed in that spot, with or without windows we could light up. So, our crew built up a plywood panel with a row of four window frames in it. This flat could be put in place anywhere that was necessary, and its windows lit up with photofloods. The effect on the screen was quite as convincing as illuminated windows in a real house, even though, as in some of the scenes made around the house used as the home of the principals, the panel was actually placed against a hedge! Of course, we had to be a bit careful not to shoot day effects from the same angle and give away the trick.

By choosing the right time of day for our night-effect shots, we were able to get quite a range of densities in our skies, so that we could suggest twilight, early evening and night very convincingly. Usually, night scenes on the screen are played very definitely as night, with inky black skies, and so on. After seeing our rushes on the screen, I feel that some of our early-evening effects, with gray yet still luminous skies, and foregrounds suggesting the artificial illumination of just turned-on streetlights, may perhaps have extended the scope of night effects somewhat. f we have, I am sure a great deal of credit must go to Director Hitchcock for his cooperation in having his cast ready to shoot when the light was right — often at an inconveniently early hour in the evening.

Frequently people who have seen these night scenes of ours have jumped to the conclusion that with such an area to illuminate we must have filmed them by day with Infra-Red film rather than actually by night. If only they’d seen how we worked to finish our night scene before the Pacific Coast’s “dim-out” order went into effect, they’d change their minds. All of our night scenes were filmed actually at night—and we just got under the wire, finishing the last one scarcely a matter of hours before the dim-out became effective.

Another very interesting part of the picture was making many of our interiors in actual buildings there in Santa Rosa. For example, we filmed a sequence in the city’s bank, another in the Western Union telegraph office, and another in an actual cocktail lounge. In the bank and telegraph office we had the inevitable problem of balancing inside lighting to a sunlit background seen through large windows. This balancing of course was taken care of by placing scrims in the windows and balancing the foreground lighting to the desired level. The result was in every way more natural than if we had tried to duplicate those rooms with studio sets, and of course more economical. Everything in the scene had a note of actuality that is difficult, indeed, to capture in a set.

We made some interiors, too, in the house used for the home of our principals — chiefly scenes in the hallway, in angles shooting toward or through the front door. In all of these practical interiors filmed up there, we were naturally limited to some extent by the physical limitations of the rooms involved. We had to light entirely from the floor, in much the same way an amateur would in making a 16mm. home movie in the same room. However, we had the advantage of being able to use spotlights, and to position them for cross and backlighting, shielding the lens with goboes. The results on the screen certainly don’t look like studio-made interiors, but they’ve an air of naturalness we don’t often get in studio interiors just because everything there can be planned for photography and lighting.

We’ve attempted to reproduce this effect, though, in the other interiors we’ve been making since we returned to the studio. I’ll admit it’s something of a strain, though, trying to keep constantly in mind that our lighting and angles must generally conform to what we could have done in a similar room up there on location! In this, though, I feel I’m fortunate to be working with so camera-minded a director as Hitchcock.

Many a director, under similar circumstances, would take it as evidence of poor cinematography if here there was an almost unbalancedly ‘hot’ light coming through a window, on to actors and back-wall alike, or if there some player had to pass through a shadow which perhaps couldn’t be avoided in real life in such a room, but in the studio could so easily be washed out by bringing in just one more lamp. But ‘Hitch’ not only understands what we’re attempting photographically, but constantly eggs me on, repeatedly asking me, ‘Are you sure this isn’t too perfect?’ or ‘Are you sure you could have done that in Santa Rosa?’

On his own part Hitchcock feels that working on actual locations like this, rather than studio-made reproductions, will result in a much more convincingly real picture. ‘A location like that,’ he says, ‘gives both of us — director and cinematographer alike — much broader scope in painting our picture.’ In some ways it was harder for both of us than making the same scenes on studio-made sets, but it paid us back with an atmosphere of actuality that couldn’t be captured any other way.” —Joseph A. Valentine (Using an Actual Town Instead of Movie Sets, American Cinematographer, October 01, 1942)

The “New Jersey” scenes mentioned by Dean Flower in the “Life” magazine spread had its own unique challenges. Hitchcock called in Universal’s newsreel division to shoot exteriors in Newark for the opening sequence that found Uncle Charlie evading a face-to-face with the detectives on his trail. Unfortunately, these shots were produced early on in the process, and Hitchcock still hadn’t nailed down his cast.

“Hitchcock shot the film’s Hackensack River backgrounds and other New Jersey setups with Actors’ Equity day players. He staged the Hemingway-inspired opening on a residential street, with two detectives staking out the boardinghouse where Uncle Charlie is cornered. Among the footage he captured was a series of high, haunting long shots over empty lots and dark deserted alleys: a bleak urban setting to contrast with the first image of Santa Rosa — an avuncular cop spreading his arms to shelter local citizens who are crossing the street. To cover all contingencies, Hitchcock shot the sequence, showing Uncle Charlie multiple times, using ‘three different men: tall, medium, and short,’ as the director later told journalist Charles Higham. ‘So, when Cotten was cast I used the shots with the tall man.’” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

“…The New York Times called the sets ‘quite a phenomenon,’ with their breakaway walls and several prop dinner tables of different sizes, allowing the camera to exploit unlikely angles in the family scenes. As much as Hitchcock was drawn to locations, he usually saved his greatest Hitchcockery — his pure-cinema highlights — for inside the studio, where the storyboards ruled, and the conditions could be manufactured.

The actors didn’t always understand Hitchcock’s sleight of hand, at least not during the shooting. Seated at the family dinner table for one scene, Hume Cronyn was supposed to react in surprise at something young Charlie (Teresa Wright) said. Hitchcock told him to rise abruptly — which the actor did, pushing off his chair and stepping back.

‘That’s all right, Hume,’ said the director, ‘but rise and step in.’ ‘Toward Teresa?’

‘Yes, step in and lean forward.’

‘But she’s just said something very offensive.’

‘I know.’

‘But … yes sir.’

Cronyn made the move as directed, he later recalled, ‘and it felt terrible, completely false.’ When Hitchcock asked for another take, Cronyn repeated his original movement, stepping back. You’ve done it wrong again, the director said. ‘I know,’ muttered Cronyn, ‘I’m terribly sorry. It just feels so uncomfortable.’

‘There’s no law that says actors have to be comfortable,’ purred Hitchcock ominously.

‘Step back if you like — but then we’ll have a comfortable actor without a head.’ After Cronyn mastered the move, Hitchcock took the screen novice aside and consoled him. ‘Come and see the rushes,’ the director urged. ‘You’ll never know which way you stepped. The camera lies, you know — not always, but sometimes. You have to learn to accommodate it when it does.’

Cronyn went to the rushes, and of course Hitchcock was right.

The actors Hitchcock took a special interest in became the sympathetic focus of his most expressive camera work. One day Teresa Wright had a question about the scene where she walks down a flight of stairs wearing a ring taken from one of Uncle Charlie’s victims. Preparing to deliver a toast, Uncle Charlie spots the incriminating ring, instantly realizes her implicit threat, and changes his toast: ‘Just in time — I’m leaving tomorrow!’ Wright understood the import of the scene but couldn’t figure out why it was taking so long to prepare the shot. Hitchcock sat down and patiently explained the technical challenges involved in sending a camera speeding into a close-up of her ring as she descends.

The resulting shot was a classic Hitchcock moment, of a kind he repeated, with variations, in countless other films. The director enjoyed the technical challenges of such bravura camera work, but it was also designed to serve the story — in this case, immersing the audience in the tension, guiding them subjectively from “the general to the particular,” in the words of screenwriter David Freeman, ‘the farthest to the nearest.’ The ‘two really spectacular shots’ in Shadow of a Doubt, in Wright’s words, were both created in the studio, and both were designed around her character. One was the scene where she confronts Uncle Charlie with the damning evidence of the ring. The other was a shot of young Charlie at the town library late one night, researching her uncle’s crimes. When she reads an article that confirms the terrible truth, the camera pulls back dramatically into an impossibly high crane shot.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

The shot has the dual effect of making her look small and vulnerable and her world seem cold and apathetic to her plight. She is all alone, and the image makes this point brilliantly. Another stroke of brilliance was the arrival of Uncle Charlie’s train as it enters Santa Rosa.

“I asked for lots of black smoke for the first scene [as the train arrives in Santa Rosa]. It’s one of those ideas for which you go to a lot of trouble, although it’s seldom noticed. But here, we were lucky. The position of the sun created a beautiful shadow over the whole station… There’s a similar detail in The Birds when Jessica Tandy, in a state of shock after having discovered the farmer’s body, takes off in her car. To sustain that emotion, I had them put smoke in the truck’s exhaust and we also made the road dusty. It also served to establish a contrast with the peaceful mood of her arrival at the farm.” —Alfred Hitchcock (Le Cinéma selon Hitchcock, 1966)

The Cast

Of course, Shadow of a Doubt owes much of its power to the phenomenal cast that Hitchcock and his team were able to assemble. In fact, the cast is so ideal that it is difficult to believe that the director originally had other people in mind for the two principal roles.

“In June he had spoken with William Powell, the comic gentleman whom Hitchcock was still eager to lure into darkness. Powell had always hesitated before, but now Hitchcock’s string of successes helped convince him to say yes. However, MGM was feeling protective of Powell’s good-guy image, and the studio refused to lend him out, insisting he was all booked up.

As usual, David O. Selznick urged Hitchcock to borrow someone under contract to him. Joan Fontaine would make an appealing young Charlie, DOS said. Hitchcock agreed, and early script treatments even described the niece as a ‘Fontaine type.’ By late May, though, the director had turned his eye to Fontaine’s older sister. Over dinner with Olivia de Havilland, Hitchcock regaled the actress with the story, and a hypnotized de Havilland said yes. But she had already signed to start shooting Princess O’Rourke for Warner’s in midsummer and wouldn’t be available until September. Though he tried several times, Hitchcock never managed to work with de Havilland.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

It was Thornton Wilder who originally suggested that Hitchcock consider using Teresa Wright for the role. The actress had been the understudy for Dorothy McGuire and Martha Scott in the role of Emily during the Broadway production of “Our Town,” and her qualities as both a person and an actress impressed the playwright. Hitchcock agreed that Wright would be ideal for the role, and it was easy to sell Jack Skirball on the idea. Wright had recently been nominated for her celebrated performance in The Little Foxes, and she would soon win an Oscar for her performance in Mrs. Miniver. She was a star on the rise that would add plenty of marquee value to the project. However, she was also under contract to Sam Goldwyn. Luckily, the mogul decided that her participation in a Hitchcock picture could only make her a more valuable commodity and agreed to loan her out to Skirball.

“Teresa did not like the Hollywood tradition of loan-outs — she considered it professional servitude, not to say a system that left actors with a considerable loss of income: on loan-outs, the actor’s boss (in this case, Goldwyn) pocketed a handsome profit, receiving a small fortune on the loan-out yet paying his contracted player only the salary fixed by their contract. But the prospect of working with Hitchcock was irresistible.” —Donald Spoto (A Girl’s Got to Breathe: The Life of Teresa Wright, 2016)

The actress was asked to take a meeting with the director, but she was never auditioned or interviewed in any formal way. He simply told her the story and gauged her reactions. Wright would later claim that “to have a master storyteller like Mr. Hitchcock tell you a story is a marvelous experience.”

“When he told me the story as we sat in his office, it was as if he had already finished the picture. He had it completely planned in his mind, along with every sound effect, and he told me the entire movie, scene by scene. He used anything on his desk as a prop — a drinking glass, a pencil or a book. He stepped around. If a character was strumming his fingers on a table, for example, it wasn’t an idle gesture — Hitch put a beat to it, like a musical pattern or a refrain. If someone was walking or rustling a newspaper, tearing an envelope or whistling, or if there was a flutter of birds or an outside sound, Hitch had everything carefully orchestrated… He really scored the sound effects the way a musician writes for instruments.” —Teresa Wright (as quoted in “The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock,” & “A Girl’s Got to Breathe: The Life of Teresa Wright,” 1983 / 2016)

Wright finally countersigned the contract on August 11 and was off to Santa Rosa only two days later. “We were the first film company to work in Santa Rosa, and everyone there got involved in one way or another,” remembered the actress. “Everyone was wonderful to us, even when our nighttime shooting interrupted their quiet routine.” She also remembered Alfred Hitchcock’s precise but simple directions rather fondly and claimed that “He would tell you what he wanted without too much instruction, and you would know exactly what to do.”

“Hitch made us all feel very relaxed, and his direction never came across as mere instruction. We felt we could trust him, and although he guided us carefully, he also gave us a sense of freedom. He was very calm, as if we were contributing to something that was already a foreseen success. No one plans a film as thoroughly as Hitch, and no one saw it as clearly as he did from the start. Other directors often let things happen during the shooting, but with Hitch’s planning, everything was more serene during production, and therefore more enjoyable . . . What luck it was for me — this was a wonderful role, a girl who starts off one way and then changes and grows before your eyes as she’s dealt this awful problem. At the conclusion, it was the end of innocence for young Charlie, because now she knows evil exists, and in the one person she and her mother love the most. She has grown up and learned that someone she has loved and been loved by can literally kill people… I had to understand how this woman felt—how she developed to include a mature, tough side, too. After all, cardboard characters are no fun. There’s no place you can go with cardboard, no depth.” —Teresa Wright (as quoted in “A Girl’s Got to Breathe: The Life of Teresa Wright,” 2016)

The actress even named it as her personal favorite of the films that she made during her career.

“Shadow of a Doubt is the picture I have taken with me all my life. I wasn’t Charlie. I was an actress. But I think maybe in some ways after that, Charlie journeyed with me all my life. More people ask me about that film than about all the others put together…” —Teresa Wright (as quoted in “It’s Only a Movie: A Personal Biography of Alfred Hitchcock,” 2005)

Meanwhile, Wright is one of the few actors that Hitchcock didn’t mind lavishing with praise in his later years.

“I got along very well with Teresa. She was easy to work with, and she made no demands. If she can’t act a line in a script, there’s something wrong with the line. She was always prepared and completely professional, she knew what she was doing, she always got things right, and she gave a great deal to the picture.” —Alfred Hitchcock (as quoted in “Spellbound by Beauty: Alfred Hitchcock and His Leading Ladies” and “A Girl’s Got to Breathe: The Life of Teresa Wright,” 2008 / 2016)

Of course, David O. Selznick was keen for Hitchcock to use someone he had under contract to portray Uncle Charlie, and it was a lucky break that the director was able to find the perfect man for the job in the Selznick stable.

“Cotten had just finished his second Orson Welles film, The Magnificent Ambersons, which Hitchcock ordered up and watched before release.) A Virginian by birth, Cotten was a new addition to the Selznick stable; he boasted the refinement of William Powell without the latter’s permanent air of bemusement. Casting Powell might have given Uncle Charlie a different coloring and a certain shock value, but Cotten was a strong second for the character Wilder had described as in his mid-forties, ‘very well-dressed,’ wearing “a red carnation in his buttonhole. His face is set in fatigue and bitterness.’ Cotten was eager to work with Hitchcock, but he worried about playing a man ‘with a most complex philosophy, which advocated the annihilation of rich widows whose greedy ambitions had rewarded their husbands with expensive funerals.’ He asked for the director’s advice. How did the character think and behave? Off they headed to talk about it over lunch at Romanoff’s, with Cotton behind the wheel…

…Cotten wondered what would go through the mind of a habitual criminal like Uncle Charlie when he spotted a policeman. Fear? Guilt? ‘Oh, entirely different thing, answered Hitchcock, warming to the subject, though even in private he was more likely to be flippant than deeply philosophical. ‘Uncle Charlie feels no guilt at all. To him, the elimination of his widows is a dedication, an important sociological contribution to civilization. Remember, when John Wilkes Booth jumped to the stage in Ford’s Theater after firing that fatal shot, he was enormously disappointed not to receive a standing ovation.’

After parking the car, Hitchcock suggested they stroll along Rodeo Drive. He told Cotten to let him know when he spotted a likely murderer. ‘There’s one with the shifty eyes,’ Cotten said, ‘he could very well be a murderer.’ ‘My dear Watson,’ Hitchcock countered, ‘those eyes are not shifty, they’ve simply been shifted. Shifted to focus upon that pretty leg emerging from a car.’ With that, the director’s glance shifted too, as his camera might in a film, anatomizing his target. ‘The rest of Claudette Colbert,’ Cotten noticed, as he wrote in ‘Vanity Will Get You Somewhere,’ followed ‘the pretty leg to the pavement.’ A light went on in Cotten’s head. ‘What you’re trying to say is, or rather what I’m saying you’re saying, is that a murderer looks and moves just like anyone else.’ ‘Or vice versa,’ Hitchcock dryly returned. ‘That completes today’s lesson.’

…

[After] Cotten drove the director home afterward… Getting out of the car at St. Cloud Road, Hitchcock offered Cotton one last bit of advice. ‘I think our secret is to achieve an effect of contrapuntal emotion. Forget trying to intellectualize about Uncle Charlie. Just be yourself. Let’s say the key to our story is emotive counterpoint; that sounds terribly intellectual. See you on the set, old bean.’” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

This was the director’s standard approach to villains. He felt that it was incredibly important for a villain to be attractive and perhaps even likeable (at least in some twisted sort of way).

“Most people don’t realize that if you have a man like the Joseph Cotten character who’s murdered three or four women for their money or jewelry or what have you, he has to be an attractive man. He’s not a murderer in the sense of a fiction murderer where the tendency would be to make him look sinister and you’d be scared of him. Not a bit. He has to be charming, attractive. If he weren’t, he’d never get near one of his victims. There was a very famous man in England called Haig, known as the Acid Bath Murderer. He murdered about four people and was a dapper, very presentable looking little man; he could never have committed these murders without being accepted.” —Alfred Hitchcock (The Men Who Made the Movies, 2001)

Cotton’s working relationship with Hitchcock was actually incredibly enjoyable, and the actor remembered working with him quite fondly.

“[Hitchcock was] really wonderfully easy to work with, one of the best directors I’ve worked with, including Orson [Welles], when we did Citizen Kane, and one of the easiest to get on with.” —Joseph Cotton (as quoted in “It’s Only a Movie: A Personal Biography of Alfred Hitchcock,” 2005)

Hitchcock was also able to obtain a stellar supporting cast.

“Dublin-born Patricia Collinge, who would play young Charlie’s mother, was also plucked from The Little Foxes — not the last William Wyler film Hitchcock would watch for casting and other inspiration. Collinge was another distinguished lady of the stage, and Hitchcock had followed her career dating back to West End appearances before World War I. The Little Foxes, for which Collinge was also Oscar nominated (in a role she first played on Broadway), had been her screen debut, too…

…Wallace Ford and MacDonald Carey played the two detectives added during script development. (Carey played the one nursing a crush on young Charlie.) Veteran character actor Henry Travers was cast as young Charlie’s father, the bank clerk who keeps up a Hitchcockian running conversation with his next-door neighbor about the latest gruesome murder cases, as juicily reported in the newspapers and pulp periodicals.

A middle-aged next-door neighbor: not an obvious part for Hume Cronyn, just thirty years old. Canadian by birth, married to the acclaimed English stage actress Jessica Tandy (who played Ophelia to Gielgud’s Hamlet, Cordelia to his Lear), Cronyn was destined to become a good friend and part of the director’s emerging brain trust in America. Although established on Broadway, Cronyn had not yet made any mark in pictures. But he had already been camera-tested by Hitchcock, and when the director spotted Cronyn at Romanoff’s one night, he was reminded of the test.

Cronyn was summoned to meet Hitchcock, who awaited him ‘with arms folded, tilted back in his chair,’ the actor remembered. ‘He wore a double-breasted blue suit; four fingers of each hand were buried in his armpits, but his thumbs stuck straight up. He weighed close to three hundred pounds and looked remarkably like a genial Buddha.’ Hitchcock began by extolling the splendors of northern California. Cronyn knew he was there to talk about a film role but waited and waited for the director to get around to mentioning it. Finally, after apparently exhausting his spiel, Hitchcock stared out the window for what seemed a very long while, then looked Cronyn over and murmured, ‘We’ll have to mess around with a little makeup — some gray in the hair perhaps — and glasses. We start shooting in about three weeks. Will you stay here or go back to New York?’ Cronyn was in.” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Another important cast member was plucked right off the streets of Santa Rosa.

“Hitchcock had spotted ten-year-old Edna May Wonacott skipping down the street with her mother. Wonacott had a girlish look: freckles, pigtails, spectacles — a mirror of Hitchcock’s own daughter, Pat, at that age. It was probably mere coincidence that Wonacott was the daughter of a local grocer, a distinction she shared with the director, but Hitchcock brought her to Hollywood and tested her, asking her to read aloud and yawn like a bored schoolgirl. She won the part of Wright’s bookworm sister…” —Patrick McGilligan (Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, 2003)

Other residents of Santa Rosa can be seen throughout the film in some of the smaller roles.

“Even when small roles were played by professionals the natives were more than ready to advise. For example, the policeman on traffic duty who admonishes Teresa Wright (playing Charlie) for running across the street with insufficient care was an actor, but constantly directed by the real traffic cop as to how he should deal with traffic at the intersection — ‘Now let some traffic through. Now let some pedestrians cross’ — and was so convincing that a woman went up to him to ask directions, as from a real policeman, and was quite surprised when he denied all knowledge with ‘I’m sorry, I’m a stranger here myself.’ The funeral of Uncle Charlie at the end was staged right in the main square, with a few professional extras, but most of the people we see on the street as the funeral cortège passes are ordinary Santa Rosans, as a matter of course stopping and taking off their hats, even to an empty coffin.” —John Russell Taylor (Hitch: The Life and Times of Alfred Hitchcock, 1978)

Release and Reception

Shadow of a Doubt was a hit both critically and commercially. Audiences were entranced, and most critics were fast to embrace the film. ‘Variety‘ is a good early example of the kind of praise that Hitchcock received from the trades.

“The suspenseful tenor of dramatics associated with director Alfred Hitchcock is utilized here to good advantage in unfolding a story of a small town and the arrival of what might prove to be a murderer… Hitchcock deftly etches his small-town characters and homey surroundings. Wright provides a sincere and persuasive portrayal as the girl, while Cotten is excellent as the motivating factor in the proceedings…” —Staff (Shadow of a Doubt, Variety, December 31, 1942)

A review in ‘Harrison’s Reports‘ followed suit.

“A very good mystery drama. From the moment the picture starts until the very end, one remains engrossed in the proceedings, because of the mystifying plot and the interesting developments. Directing with his well-known flare for suspense, Alfred Hitchcock has made the most of the story, which deals with the adoration of a young small-town girl for her ingratiating big-city uncle, and the disintegration of this adoration when a web of circumstances slowly reveals to her that he is a maniacal killer wanted by the police. The action settles down to a battle of wits in which the uncle seeks to kill his niece to save himself, and the niece seeks to get him out of town lest her family, too, become disillusioned. The performances are very good.” —Staff (Shadow of a Doubt, Harrison’s Reports, January 16, 1943)

A review published in ‘Time‘ magazine reminds us of the thematic similarities it shares with Suspicion (which was still very much in the public’s collective memory in 1943).

“This Hitchcock masterpiece has the same general theme as his Suspicion — the slow, terrible growth of fear of a loved one — but Shadow, from beginning to end, is a surpassingly better picture. Its horror is compounded by its setting: an exquisitely commonplace family in a familiar small California town… Slowly the menace, seen through the girl’s eyes, grows palpable, until the dull, homely old house itself seems terrifying… By skillful transfer of emotion, director Hitchcock loads the most commonplace things with ominous overtones. A broken porch step, a cranky garage door, the cheerful family bickering at the dinner table, a traffic cop’s scolding as the girl runs across a street to the library — these become major elements in building up a crescendo of terror. Unlike Suspicion, Shadow hits few false notes [and] maintains suspense to the end, but good as director Hitchcock and actor Cotten are, the show is really Miss Wright’s.” —Staff (The New Pictures, Time, January 18, 1943)

Shadow of a Doubt was also embraced by critics in other territories. One example was a short but very kind review that was published in the London ‘Evening Standard.’

“An Alfred Hitchcock picture is something of an event. This one… is an ingenious and unorthodox thriller which is continuously entertaining… The suspense is maintained to the end, and there is an exciting climax.” —Staff (Evening Standard, March 27, 1943)

‘The Times‘ was just as enthusiastic about the film and echoed Time in its favorable comparison to Suspicion.

“This film sees Mr. Alfred Hitchcock at his best, and a good Hitchcock film is one of the greatest treats the cinema has to offer. In his last two or three films he had shown a disturbing tendency to substitute mechanical tricks for psychological subtlety as his means of building up an atmosphere of suspense, but here he succeeds, where in Suspicion he lamentably failed, and the attention of the audience is riveted as much on the nature of the characters as on the plot in which they are involved.

All the time Mr. Hitchcock has been content to hint, and he has in his camera and soundtrack allies cunning in the art of suggestion. The presence of Mr. Cotten, one of the Mercury players, stresses the resemblance of the film’s methods to those of Mr. Orson Welles, but it would not be fair to make too much of this — the core of the film’s excellence is Mr. Hitchcock’s own. The end is neat and ironical, but not too artificially so, and Shadow of a Doubt will long stay in the mind as a” film of tense and cumulative interest.” —Staff (New Films in London: Mr. Hitchcock Returns to Form, The Times March 29, 1943)

‘The Times‘ wasn’t the only publication to suggest that Hitchcock had been influenced by Orson Welles. ‘The Sydney Morning Herald‘ built their entire review around the idea (without giving any specific examples).

“Alfred Hitchcock has borrowed other things than Orson Welles’s leading man, Joseph Cotton, for his new film Shadow of a Doubt. He uses, too, not a few of the Wellesian tricks for exploiting camera and background music. Perhaps Hitchcock is big enough to borrow another man’s ideas, regardless of their innate individualism, if he thinks them worthy of use in one of his own films. Certainly, his borrowing in Shadow of a Doubt has been successful. Cotton gives a performance ranking at least equally with [Robert] Montgomery’s Danny in Night Must Fall and the Wellesian technique is well suited for this type of film. With a full quota of ideas which are purely Hitchcock, however, added to those lifted straight from Welles, the spectator’s view of the woods sometimes is obscured by the trees. Nevertheless, Shadow of a Doubt is a great film. Hitchcock gradually increases the tension with the same skill he did in Suspicion… Master of the suspense drama that he is, Hitchcock keeps his climax for the very end. The final curtain is a glorious piece of cynicism.” —Staff (New Films: Shadow of a Doubt, The Sydney Morning Herald, November 22, 1943)

The writer of this particular review had obviously not seen very many Hitchcock titles if they attribute any of his stylistic flourishes to Welles considering the fact that he was using them as early as The Lodger (1927). If anything, Welles took a few pages from Hitchcock’s book (and would “borrow” more when it came time for him to make The Stranger (1946). The ridiculousness of the notion that Hitchcock had borrowed anything beyond one of his Mercury Players from Orson Welles might distract us from the fact that these reviews followed in a very long line of very good notices.

However, a few of the reviews were mixed or mixed. For example, Bosley Crowther had a mixed (and somewhat condescending) reaction to the film:

“…Yes, the way Mr. Hitchcock folds suggestions very casually into the furrows of his film, the way he can make a torn newspaper, or the sharpened inflection of a person’s voice send ticklish roots down to the subsoil of a customer’s anxiety, is a wondrous, invariable accomplishment. And the mental anguish he can thereby create, apparently in the minds of his characters but actually in the psyche of you, is of championship proportions and — being hokum, anyhow — a sheer delight.

But when Mr. Hitchcock and/or his writers start weaving allegories in his films or, worse still, neglect to spring surprises after the ground has apparently been prepared, the consequence is something less than cheering. And that is the principal fault — or rather, the sole disappointment — in Shadow of a Doubt. For this one suggests tremendous promise when a sinister character — a gentleman called Uncle Charlie — goes to visit with relatives, a typical American family, in a quiet California town. The atmosphere is charged with electricity when the daughter of the family, Uncle Charlie’s namesake, begins to grow strangely suspicious of this moody, cryptic guest in the house. And the story seems loaded for fireworks and a beautiful explosion of surprise when the scared girl discovers that Uncle Charlie is really a murderer of rich, fat widows, wanted back East.