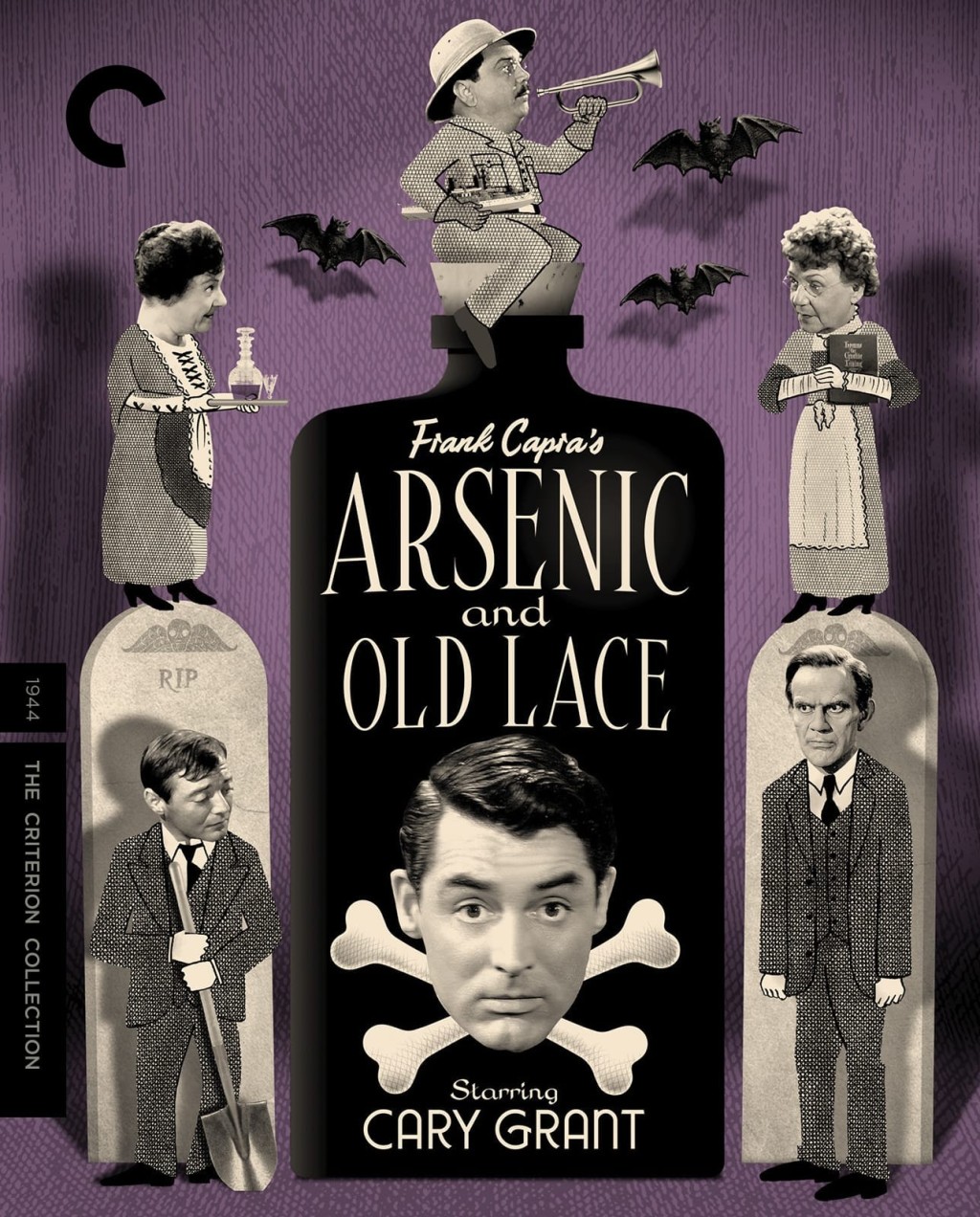

Spine #1153

Distributor: Criterion Collection (USA)

Release Date: October 11, 2022

Region: Region A

Length: 01:58:15

Video: 1080P (MPEG-4, AVC)

Main Audio: 1.0 English Linear PCM Audio (48 kHz, 1152 kbps, 24-bit)

Subtitles: English (SDH)

Ratio: 1.37:1

Bitrate: 35.92 Mbps

Notes: This is the film’s Blu-ray debut.

“A lot of movies are about life, mine are like a slice of cake.” —Alfred Hitchcock

It might seem odd to our readers that this article should open with a quote from Alfred Hitchcock, but it seems to us a pertinent opening for a discussion about Arsenic and Old Lace because the film is something of a rarity in Frank Capra’s filmography. Capra tended to direct films that had quite a lot of social commentary embedded within the material, but this film is purely “a slice of cake.”

“I owe myself a picture like this,” Capra claimed after watching the play on Broadway for a second time. “I’m not going to try to reform anybody. It’ll be a picture without a sermon, and I’m going to have a lot of fun… For a long time now I’ve been preaching one thing or another. Why, I haven’t had a real good time since It Happened One Night.”

Of course, this material was quite a bit different than It Happened One Night, and that film managed to offer glimpses of a suffering lower class. Arsenic and Old Lace is a comedy that involves a pair of kindly old ladies who have the unfortunate habit of killing off lonely old men with their very special 3-poison recipe added to a nice glass of elderberry wine. In fact, the material seems more in line with the kind of gallows humor that Hitchcock enjoyed than the kind of material that Capra was known for creating. It almost makes one wonder what the master of suspense might have done with the same material but getting into this would be an unnecessary digression.

The truth is that this change of pace was a conscious decision on Capra’s part as he was at something of a crossroads. His previous film, Meet John Doe, was a succès d’estime and even became a modest success at the box-office, but Capra’s decision to produce the movie himself placed him in a financial jam. The federal laws at the time required the producers of a film to pay taxes on the film’s income before it ever came in, and this forced them to dissolve their corporation so that they could pay Uncle Sam. In addition to this, Capra was about to begin a stint in the Army.

“I knew I was going into the Army. I had volunteered the year before, and the way things were happening, it was only a matter of time before we were in war — it seemed imminent. And I thought, ‘Well, if I go into the Army, I’d like to have something going for my family while I’m there. Perhaps I can find a picture that I can make fast and get a percentage of the profits. Then that will keep them going, it’ll be something for them. So, I saw ‘Arsenic and Old Lace’ on the stage in New York, fell in love with it, and I said, ‘Here’s the thing I can do fast, quickly, I can do it in one set.’ Then I found out that Warner Brothers had already bought it, but they couldn’t make the film for another three or four years because that’s how long the play would run and they couldn’t make the film out of it until the play stopped running, which might be three years from then, which would spoil my plans. But anyhow I didn’t give up. I said, ‘Could I make that film for you now? … Warner said, ‘But I can’t release it now.’ I said, ‘Well, I know, but you can release it later. I’ll make it now.’ I talked him into it…” —Frank Capra (The Men Who Made the Movies, 2001)

Joseph McBride suggests that Capra’s interest in the property went beyond a genuine affection for the material and the aforementioned need for creating a financial cushion for his family in the wake of his tax issues.

“The play was produced on stage by Howard Lindsay and Russel Grouse, who had rewritten Kesselring’s original version, ‘Bodies in Our Cellar,’ without credit… [Capra] earlier had made an offer to Lindsay and Grouse for their long-running play of Clarence Day’s ‘Life with Father,’ which opened on Broadway in November 1939 and was still playing, with Lindsay in the lead role of the crusty patriarch Father Day. But the playwrights had rejected the offer because Capra demanded script control, a concession they felt they would not have to make if they held out longer (when the play reached the screen in 1947, directed for Warners by Michael Curtiz, it was filmed intact but was disappointingly stodgy and long-winded). Nor was Capra the first choice of Lindsay and Grouse to direct Arsenic: they preferred Rene Glair but went with Capra because he had a more commercial reputation. Capra admitted to Lindsay and Grouse that he took on Arsenic partly as a way of persuading them to let him make Life with Father, but he also needed cash to help pay his taxes on Meet John Doe. Jack Warner agreed to pay him $100,000 in twenty weekly installments, in addition to $25,000 for five weeks of editing and 10 percent of the gross receipts in excess of $1.25 million. The film was budgeted at $1.22 million…

…There may have [also] been a subconscious cause for Capra’s attraction to Arsenic and Old Lace: making the film may have been his way of trying to work out his complex emotions about his mother — who died on May 23 at the age of eighty-one, shortly before he decided to make it — and his way of expressing his compulsive need to escape from his family. Much of the film’s underlying emotional frenzy turns on Mortimer’s fear of inheriting his family’s psychoses: he tells his new bride, Elaine Harper (Priscilla Lane), ‘Insanity runs in my family — it practically gallops!’ Josie Campisi described the Capra family as ‘crazy,’ and Capra described his own mother as having been ‘nuts.’

The two superficially lovable little old ladies in Arsenic, Abby (Josephine Hull) and Martha (Jean Adair), who resemble the celebrated ‘pixilated sisters’ of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, have poisoned twelve lonely old men with elderberry wine laced with arsenic, strychnine, and cyanide. The comedy comes from their utter inability to see that, as Mortimer puts it, what they are doing is ‘not only against the law; it’s wrong.’ In almost every other conventional sense they are principled Yankee ladies and pillars of society, a class toward which Capra had reason to be ambivalent — Abby has a disturbing tendency to disparage ‘foreigners,’ and she says she is happy to go to a mental institution at the end because the neighborhood has ‘changed.’ Behind the facade is a comic, American Gothic version of the House of Atreus, a legacy of family lunacy and violence which, as Mortimer puts it, ‘goes back to the first Brewster, the one who came over on the Mayflower.’ The Brewsters’ Yankeedom has a sly appeal to Capra, who similarly relishes the film’s implications of insanity in the Roosevelt lineage: Teddy Brewster, who thinks he is President Theodore Roosevelt, confides that he is planning to run for a third term, like his distant relative FDR, ‘if the country insists’; Mortimer even tells him, ‘The name Brewster is code for Roosevelt.’

Like Aunt Abby and Aunt Martha, Capra’s mother was a woman with many obviously respectable qualities, a lovable figure to people who did not know her well, but a ‘hard woman’to her family and a figure of terror to her son Frank, who called the house in which he grew up ‘a house of pain.’ And, like the Brewster ladies, she made her own wine in the basement. Frank Capra, like Mortimer, felt estranged from his family from an early age, and he had a brother (Tony) who, like Massey’s Jonathan Brewster, tormented him and grew up to become a criminal. ‘As a boy I couldn’t wait to escape from this house,’ Jonathan tells Mortimer, whose entire life has been an escape, from his home and family, from reality (his absorption in the theater), and, like Capra before he married Lu, from emotional involvement with women (before his marriage Mortimer was a notorious Don Juan, the author of such books as ‘The Bachelor’s Bible’ and ‘Mind over Matrimony’).

‘The crux of the play,’ said Julius Epstein, ‘was that Mortimer couldn’t marry the girl because he thought there was insanity in his family. But at the end, when his aunts tell him he’s illegitimate, he says with great relief, ‘Darling, I’m a bastard!’ In the film, the undercurrent of sexual frustration is intensified by having the couple sneak off to marry at the beginning but being prevented from leaving for their honeymoon and consummating their marriage until the aunts, Jonathan, and Teddy are safely packed away to the asylum and Mortimer resolves the question of his lineage… The giddy, out-of-control tone of Arsenic and Old Lace, with its feeling of helplessness and abandon in the face of irrational impulses toward sex and violence, its mockery of death, and its ultimate sense of catharsis, is a dark celebration, perhaps, of Capra’s feeling of release from his mother and from his family, and his exorcism of the guilt stemming from that forbidden feeling.” —Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

Of course, both of these two sources tend to gloss over the fact that convincing Jack Warner to allow Capra to shoot the film only to turn around and sit on it for years at a time took a lot of planning and effort. The director knew that he couldn’t broach the topic without talent attached or without first coming up with a preliminary budget.

“I think I offered twenty-five thousand dollars each to Josephine Hull and Jean Adair, and fifteen thousand dollars to John Alexander for four weeks of their vacation time in Hollywood and warned them the deal was ‘iffy’ and that any advance publicity could kill it. Then I rushed back to the West Coast to weave the rest of the plot — and plot it was.

Nobody could expect Jack Warner, or any other studio head, to sink a barrel of money in a film and then lock it up in vaults for four years. There were risks: wars, depressions, changes in fads and clothes. Members of the cast might die or fall into disfavor with audiences. Interest on the tied-up money would up the film’s cost, but I counted heavily on Jack Warner’s quixotic strain. He was a sucker for the unusual. If I could bait the trap with a lure that was both complete and compelling — he might just go for it.

Next on the scheme’s agenda was a star. Cary Grant was Hollywood’s greatest farceur. He was also one of its greatest box-office lures, and he wanted one hundred thousand dollars to make the picture. I [also] had a quiet meeting with the Warner Brothers production staff [and asked them to prepare a “below-the-line” budget estimate] … My homework on Jack Warner unearthed this warning: Though Jack likes his laughs, never try to clown him into a deal. Many who tried had felt the heft of his follow-through as they went flying out the door. So, armed with facts and figures, but no gags, I stepped into his office.” —Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

Obviously, his homework paid off. The director signed his contract with Jack Warner on August 01, 1941, but there is reason to believe that Grant’s participation was the deal clincher. Warner wanted to make the film while Grant was still available, and they only had a six-week window in which to engage the actor. Interestingly, Capra actually considered other actors for the role of Mortimer Brewster (who was portrayed by Allyn Joslyn in the original Broadway production of the play) before deciding that Grant would be a more convincing bargaining chip. None of his other choices (Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and Ronald Reagan) could draw a crowd like Grant, and the actor was convinced to sign on to the project only after he was offered $160,000 (which was quite a bit more money than Capra’s own salary). Apparently, the actor ended up donating $100,000 of his fee to wartime charities.

Much of the rest of the cast depended heavily on the generosity of Lindsay and Grouse.

“After failing to convince Warners to wait until the summer of 1942 so they could keep their cast together, [Lindsay and Grouse] agreed to loan Capra their two lead actresses, Josephine Hull and Jean Adair, for only eight weeks, including two weeks of travel time by train. When Andy Devine, whom Capra wanted for the bugle-blowing ‘Teddy,’ was unavailable, they also agreed to let him have the actor who played the role on stage, John Alexander.

The producers balked, however, at Capra’s request for Boris Karloff. Karloff was playing Jonathan, the old ladies’ criminal nephew who had been turned into a replica of Karloff s Frankenstein monster by his drunken plastic surgeon, Dr. Einstein. An investor in the play, Karloff was its star attraction, and the producers were counting on him to continue bringing in capacity audiences while the other regulars were in Hollywood. Lindsay and Grouse told Capra they would give him Karloff if Warners agreed to let them borrow Humphrey Bogart, but Capra was unable to persuade Warners to make the swap. After considering Sam Jaffe for the part, Capra decided to use Raymond Massey (whom he had tested for the High Lama in Lost Horizon) in Karloff-like makeup, to the dismay of Lindsay and Grouse. Peter Lorre was cast as Einstein.” —Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

Capra claims that “preparation wheels began spinning” for Arsenic and Old Lace immediately after signing his contract with Jack Warner, and this is probably true since he was in a rush to finish one more film before having to go into the Army. Julius J. Epstein and Philip G. Epstein (who would also script the narration for Capra’s Why We Fight series) were charged with the task of making certain changes to Joseph Kesselring’s original hit play, but they were instructed to stick as closely to the original text as was possible under the production code.

“‘We had very little personal contact with Capra in writing the script, because it was abnormally such a good situation,’ Epstein said. ‘The only big challenge was that you couldn’t say ‘‘bastard’’ on screen in those days; you couldn’t even say ‘‘hell.’’ We couldn’t use the line ‘‘Darling, I’m a bastard,’’ but when I saw it in the theater it brought down the house. For a while we didn’t think we’d get it, but my brother came up with a solution. Mortimer’s father was a cook on a tramp steamer, and Mortimer told the girl, ‘‘I’m not really a Brewster, I’m a son of a sea cook!’’ I don’t know why, but that line was almost as effective in the picture as ‘‘Darling, I’m a bastard!’’ was in the play.’” —Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

Another change that had to be made in an effort to appease the censors was the play’s original ending. Originally, the story ends at the Happy Dale Sanitarium. The two sisters entertain Mr. Witherspoon (the sanitarium director) and pour him some of their famous wine. A new ending was created by adding a running gag that involves a cab driver waiting outside the Brewster residence with his meter running while Mortimer tries attend to the problem with his murderous aunts. The cab driver is actually given the film’s closing joke (which I will not reveal here as that would be an unnecessary spoiler). Another major addition to the original play was the introductory opening sequence. Capra opens his film on a riot at Dodger’s stadium to establish the Brooklyn setting before catching up to Mortimer and Elaine as they apply for their marriage license. The couple is forced to dodge members of the press because Mortimer is a well-known bachelor who has published numeral books that publicly denounce marriage. In the play, he is merely a drama critic. Of course, incidental bits of dialogue also had to be altered to accommodate this change.

Pre-production moved at an extremely swift pace, but the speedy nature of the production itself has been largely exaggerated by the director. A good example of this would be the Capra’s spin on an early meeting with his production staff that appears in his autobiography.

“I had a quiet meeting with the Warner Brothers production staff. ‘Boys, Jack Warner doesn’t want this to leak out. Make me a quick budget estimate of the below-the-line costs for Arsenic and Old Lace (the costs of story, director, and cast were called above-the-line). Here are the details: an all-Warner crew — camera, sound, lighting, editing. Lay the picture out on a four-week schedule—’

‘Frank! You’re gonna shoot a picture in four weeks?’ asked an art director.

‘Please, will you? The schedule is four weeks, and not a day over. Now. There’ll be no extras, no locations, no transportation costs — except for round-trip fares for three actors from New York, and fifty bucks a day each for living expenses. Got that? Now, here’s the news! The whole picture will be shot in the studio, on one stage, in one set — a spooky, two-story, old Brooklyn house next to a cemetery. Here, these are some sketches, exterior and interior.

‘Build the front and left side of the house wild, so we can shoot inside and out. Some broken down tombstones in the foreground, see? And diminish them in the distance. Far off we see the two-dimensional profiles of the skyscrapers in Manhattan’s skyline. It’s night. Lights in the windows, glow over the city, colored neons that blink, and a couple of scrims in front of the skyscrapers to make them look far off. In back of the old house, build a fast-diminishing, three-quarter-angle miniature of the Brooklyn Bridge, with little miniature trains and cars that move. Got it?

‘The backing is a night sky. Paint some wispy clouds in front of a full moon — you know, ghostly, Halloweenish. And allow for bags and bags of autumn leaves to blow around the house and tombstones. Oh, yes — and three silent wind machines. Any other details you want?’

‘Is all the shooting at night?’

‘All the exteriors are at night. There’ll be a few day scenes inside the house. And oh! In the living room, under the left window, figure in the cost of a window seat with a creaking lid, and big enough to hold a body. And don’t forget the creaking door and the steep stairs down to the dirt cellar where the old ladies bury the bodies. Anything else?’

‘Shall we allow for Camera booms?’

‘Yes. The ‘A’ camera will never be off a Chapman twenty-foot silent boom. The ‘B’ camera will be wild. Okay, fellas. And never mind padding the figures for ’emergencies.’ If you come up with a below-the-line cost of more than four hundred thousand — you’re cheating.’

‘What’re you doing, Frank,’ kidded production manager Steve Trilling, ‘going back to your Poverty Row quickies?’

‘Yep. For a refresher course. See you.’” —Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

Certain aspects of this yarn may very well be true, but we know from production documents and numerous other sources that the film wasn’t finished “in about four weeks” as the director always insisted. What’s more, he never intended to shoot the film in such a short span of time.

“Though he completed the film one day ahead of schedule, the shooting actually took more than eight weeks, and by mid-November Capra was requesting a two-week extension of the actors’ contracts. This prompted a frantic plea from Lindsay and Grouse to Jack Warner that their actors be returned before Christmas, as planned, because box-office receipts were slipping in their absence. Capra suggested suspending production and resuming in the spring, but Warner refused. He begged Lindsay and Grouse for more time, telling them he could improve Hull’s and Adair’s performances by reshooting some of their early scenes, but they insisted he keep to the schedule. Capra accelerated his pace and managed to finish with Grant, Hull, and Adair by December 13, bringing the somewhat slapdash picture to a halt three days later at a cost of $1,120,175 — or $99,825 under budget.” —Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

The most notable interruption to the brisk production schedule was the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 07, 1941. Capra wrote at length about this in his autobiography.

“…The fun had one more week to go, when it was brutally interrupted by — PEARL HARBOR! Next day, Monday morning, December 08, two Signal Corps officers came to the studio stage to swear me in. I was in the Army. I asked for, and was granted, six weeks’ leave of absence to finish, edit, and preview Arsenic. Nights, a tailor fitted me for uniforms. A little frightened by it all, I entered an Army-Navy store to try on caps and buy some major’s leaves and Signal Corps crossed-flags insignia. I had no idea how to put them on and neither did the tailor. On February 05, I received this telegram:

MAJOR FRANK CAPRA…

YOU WILL PROCEED ON FEBRUARY ELEVENTH TO WASHINGTON DC REPORTING CHIEF SIGNAL OFFICER FOR DUTY

ADAMS ADJT GENL WASHN DC

That’s a pretty cheeky order, I thought. Not ‘Please proceed,’ or ‘Kindly proceed,’ but ‘You will proceed …’ I suppose it was in my blood to resent arbitrary authority.” —Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

Of course, Joseph McBride directly contradicts this in his biography about Capra.

“It was on December 12, five days after Pearl Harbor, that Capra agreed to join the Signal Corps with a major’s commission and announced his decision to the press. He was ordered to report for active duty on January 15, but he later received an extension of almost a month so he could complete the editing of Arsenic before reporting to Washington. The date he finally took his Army oath was January 29, 1942, and it was not on a film set but at the Southern California Military District Headquarters in Los Angeles… By the first weekend in January Capra was back in Hollywood to complete the last film he would make as a civilian for more than four years. After a preview of Arsenic on January 30 and some frantic re-cutting, he left for active duty with the Signal Corps on February 11.” —Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

Another obstacle in Capra’s path — and one he rarely if ever spoke about — was that his leading man disliked being forced into such a broad comedic performance. “This is something new for me,’ Grant graciously admitted to one journalist during the film’s production. “I always play the calm, hands-in-the-pocket guy who tosses the answers off to the excited people. But here I’m the one who is always bouncing around. It’s an entirely different side of comedy. If it weren’t for Frank’s helping me, I wouldn’t know what I am doing half the time.” Of course, the actor was glossing over his growing doubts concerning his performance.

The truth is that Grant could be difficult if he wasn’t confident in a project, and his portrayal of Mortimer Brewster was a performance he always loathed. “I was embarrassed doing it,” he would later insist. “I overplayed the character… Jimmy Stewart would have been much better in the film.” Julius Epstein (one of the twin brothers responsible for the film’s screenplay) agreed with the actor and would later claim that Grant “mugged too much.” A lot of critics throughout the years (Pauline Kael among them) agreed with Grant and Epstein, but Richard Schickel defends it in his book about Grant’s filmography.

“There are those who think his Mortimer Brewster was also miscalculated: too frenzied in its cowardice, too manic in its pursuits of laughs. It is surely not his most urbane performance. And yet there is something courageous in his outrageousness. It is as close as he ever came to giving a Hawksian performance for any director but Hawks. And it works. It is mostly his energy that permits the film to burst its stage boundaries and turn it into a moving picture. And anyway, what’s a man supposed to do when he finds bodies buried all over his maiden aunts’ house? Arch an ironic eyebrow? Hone a Wildean epigram on the subject? No, let those big brown eyes pop and roll! Let the voice rise into the boy soprano range!” —Richard Schickel (Cary Grant: A Celebration, 1983)

It is hard not to question Grant’s dismissal of the film after considering some of the actor’s other over-the-top roles. Had he forgotten about Bringing Up Baby (1938)? One feels that there were probably personal factors behind his attitude about the movie, but speculation as to what these personal issues actually were could only be conjecture. If he didn’t enjoy his performance, it must have at least tickled the actor to find that the name Archibald Leach was prominently displayed on one of the tombstones seen in a nearby cemetery. It was an in-joke that would have appealed to Grant’s sense of humor. He was also comforted by the presence of Jean Adair.

“Twenty years earlier, when he was still Archie Leach, he had contracted a fever on a vaudeville tour, and Adair had nursed him through the illness. Adair had very little movie experience and relied on Grant to properly scale her performance.” —Scott Eyman (Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise, 2020)

Capra never even discussed any conflict with Grant and only had praise for the actor.

“Grant is a great comedian — a great light comedian. He’s very good looking, but he’s also very funny. That makes a devastating combination, and that’s why he’s been a star so long. I think he’s been a star for forty years and is still a star today because he is a great entertainer. And fun to work with, lots of fun to work with.” —Frank Capra (The Men Who Made the Movies, 2001)

While the production was a happy memory for Capra, he always claimed that the play remained on the Broadway stage too long (1,444 performances) for the film’s eventual release to sustain his family while he was away in the Army.

“You will probably remember the big plot to make Arsenic and Old Lace on a percentage basis so that I wouldn’t have to dig into the old sock to keep my family going while I was in uniform. How did the plot work out? A disaster. The picture was not played in theaters until 1944. Then it made money so fast my first percentage check was for $232,000! Great! Oh, sure. The Federal and State income taxes on it added up to $205,000!” —Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

However, Joseph McBride later countered that Capra misrepresented (or at least oversimplified) the situation.

“His final paycheck on Arsenic and Old Lace had been on January 22, 1942, when he received the last $20,000 of his $125,000 salary. He added that in 1942 he had received $135,910 in net profits from Meet John Doe, that profits on the film still were accruing ‘in ever-dwindling amounts,’ and that since entering the service he also had received profits from his Columbia films. He made no mention of the income from Red Mountain Ranch and its mail-order olive oil business nor from any of his stock holdings. He later claimed he had withdrawn more than $150,000 from his savings during the war years and had a $205,000 tax bite taken from his first profit participation payment of $232,000 from Arsenic after its theatrical release in 1944. But his book misleadingly implies that his family lived during the war entirely on his income from Arsenic, with their total expenses amounting to only about $25,000 per year. Capra’s obfuscations not only exaggerated the degree of his wartime financial sacrifice but also reflected a genuine anxiety he felt about his reduced income level, even though the war had made him see that ‘the crazy spending was a lot of chichi.’” —Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

Luckily, Warner Brothers was able to release the film people in various branches of the military “a full year” before they could legally release it to the general public.

“In the blacked-out London it was easy to recognize American soldiers’ voices in Piccadilly Circus, or in Grosvenor Square (nicknamed ‘Eisenhower Platz’). A couple of times, listening to G.I.’s horse-playing around, I heard them shout: ‘Charge!’ Soon after, at the R.A.F. mess at Pinewood, several British flyers came running up to my table, brandishing imaginary cutlasses and yelling: ‘Charge!’ I pointed my finger at them and cried out: ‘You guys have seen Arsenic and Old Lace — right?’” —Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

Arsenic and Old Lace finally premiered in New York on September 01, 1944, before going into general release a few weeks later on September 24. The film was a modest success both critically and financially, but its real triumph is surviving the test of time. It has become something of a cult classic, and we watch it in our house every October.

The Presentation:

4.5 of 5 Stars

Criterion protects their disc in one of the clear cases that is the standard for Criterion titles and includes a dual sided insert sleeve that includes a new cover design by F. Ron Miller. There is a still from the film on the opposite side so that one sees it once the case is opened. This case also houses a pamphlet that features an essay by David Cairns entitled “Madness in the Family” that is informative and well worth reading. The pamphlet also includes production photographs, the customary transfer information, and various credits.

The menu utilizes a still production photo of Cary Grant with a layout that will be familiar to those who own other Criterion Blu-rays, but even those who don’t will find it intuitive to navigate.

Picture Quality:

4 of 5 Stars

The Criterion Collection offers a transfer that bests the old Warner Brothers DVDs in all respects. Of course, this will come as a surprise to absolutely no one considering that the added resolution alone would be enough to improve most aspects of the image. The transfer information isn’t quite as elaborate as is usually the case for Criterion, but we do know that it comes from a new 4K master taken from the original 35mm nitrate negative. This results in an image with plenty of incredibly sharp fine detail for a film produced in the early 1940s, and this new 1.37:1 transfer seems to be more detail at the sides of the frame than was evident in the earlier 1.33:1 DVD editions. Depth and Clarity are also dramatically improved here. There is also a more noticeable but never distracting layer of organic grain that retains the original filmic texture of the image. Contrast is well handled (although some may feel that the blacks are pushed a bit too far). There is a surprisingly nuanced range between the various shades of grey, and blacks are incredibly deep without sacrificing any obvious details in the shadows. Sol Polito’s cinematography was supposed to look this way, and it is nice to see that the film is finally on a format that can actually support the intended aesthetic. The film’s original cinematography was intended to look like this, It is an incredibly clean image as stains, dirt, and other kinds of age related damage has been removed. The one downside is that some viewers may notice macro blocking issues in some of the darker scenes. Frankly, I didn’t notice them until I was watching the movie a third time and scrutinizing the image for flaws, but it is still worth mentioning. It still bests earlier DVDs in every single way, and it warrants an upgrade.

Sound Quality:

5 of 5 Stars

Criterion’s faithful 1.0 Linear PCM audio transfer reproduces the original mono track faithfully and gives it a new life. Everything sounds much better here than it has ever sounded on home video. Dialogue is clean and clear, and Max Steiner’s score has more room to breathe. The mix is well handled for a film of this period. I’d even go as far as to say that it is impressive. Distortion is never an issue, and there aren’t any signs of age-related damage. This is one of those tracks that purists should be able to enthusiastically embrace.

Special Features:

3.5 of 5 Stars

Feature Length Audio Commentary with Charles Dennis

Charles Dennis offers one of the best third-party commentaries I’ve heard in a very long time. Dennis wrote a book entitled “There’s a Body in the Window Seat: The History of Arsenic and Old Lace” that is set for release in November, and this track should be enough to interest cinephiles in a purchase as it is full of interesting information that is delivered in a surprisingly entertaining manner. It covers information about the original play, the production of the film, biographical information about the actors, censorship information, and just about anything else fans might be interested in knowing. There are a few dead spots, but they don’t last long enough for the listener to become bored. Some might complain that Criterion doesn’t have a very robust supplemental package for this release, but this track probably has as much or more information than one should expect from any release (especially these days).

“Best Plays” Radio Adaptation (1952) — (59:24)

This radio broadcast of Arsenic and Old Lace is from an NBC program called “Best Plays” and stars Boris Karloff (who also appeared in the original Broadway production). It’s a great addition to the disc and offers the opportunity to hear Karloff in the role Capra wanted him to play in his film adaptation.

Theatrical Trailer — (02:49)

Finally, Criterion includes the film’s original trailer for the film. It is a silly trailer that makes Grant’s over the top performance the primary selling point.

Final Words:

“No great social document ‘to save the world,’ no worries about whether John Doe should or should not jump; just good old-fashioned theater — an anything goes, rip-roaring comedy about murder. I let the scene stealers run wild; for the actors it was a mugger’s ball.” —Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

Arsenic and Old Lace is indeed a “mugger’s ball,” and it is one of the silliest black comedies ever made. Fans should be thrilled to learn that Criterion is finally bringing the film to the Blu-ray format. It comes highly recommended!

Review by: Devon Powell

Source Materials

Frank Capra (Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title, 1971)

Richard Schickel (Cary Grant: A Celebration, 1983)

Joseph McBride (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, 1992)

Geoffrey Wansell (Cary Grant: Dark Angel, 1996)

Richard Schickel (The Men Who Made the Movies, 2001)

Scott Eyman (Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise, 2020)

Rob Nixon (Arsenic and Old Lace: The Big Idea, TCM)

Note: We were provided with a screener for review purposes, but this had no bearing on our opinions.

Reblogged this on Blu-ray Downlow.

It heartens me to see you’re still doing your excellent, highly-detailed reviews (and I love Arsenic and Old Lace). I do miss talking to you about old films. It really is so rare, for me anyway, to meet people with shared passions. I ruined what could have been a great friendship by a ridiculous, emotional blunder, saying things I didn’t even mean just because I got frustrated. I think B- was right that we would click, I just messed that up and take full blame. I wanted to apologize soon after, although I have no idea if that apology ever got to you. I really do wish you the best, I hope you are well, and I’m so happy to see that your passion still burns so brightly. I’ll always admire that. I do apologize for the more personal reply, but I figured you could delete it and I’d at least know for sure that you got that apology you deserved long ago.

I’m glad that you are doing okay. I haven’t been on Facebook very much. Happy Holidays.

You blocked me there so I couldn’t contact you anyway lol. I do miss you and think of you every so often. I hope you have a wonderful holiday, too. I started it with The Man Who Came to Dinner. ^^

Great film! I hope your Holidays were great too. 🙂